Our cultural script on pregnancy insists on certainty. Whether the authorities are doctors or majority-male legislatures, we are assured that humans know — that we know how to know — what pregnant people should eat, whether growing babies are getting big enough, when they can live outside their mothers’ bodies.

But to be pregnant is to be in doubt. Is the bubbling sensation in my belly just gas, or is it a future baby rolling over? I’m told that I “can’t miss” the fetus hiccupping, but eight months in, I still don’t know what her hiccup feels like inside my body and, therefore, whether I’ve ever felt it at all.

Much of this, no one can clarify, not even the most confident doctors. Theirs is well-ornamented guesswork — so many lab results! — but guesswork nonetheless. Instead of facts, there are figures — descriptive numbers, like 112, that are normal, in the case of the test I am given, for glucose levels but low, I’m told, for my blood pressure. Even normal figures are only momentary facts. In three weeks, who knows? My numbers could change, and I’ll be preeclamptic, or diabetic.

Probabilities are, strangely, more certain; they will not change with my changing body. Twenty-five percent is our chance of having given our child spinal muscular atrophy, if my partner, like me, carries the gene. (For arcane reasons, we can’t test him to find out.) One in two is the chance that our baby will have a chromosomal abnormality.

A saccharine-voiced geneticist reads me these odds over the phone. I panic at first, but she says, intending reassurance, that nothing is certain — not yet. The only way to know — to rule, decisively, on these probabilities — is amniocentesis.

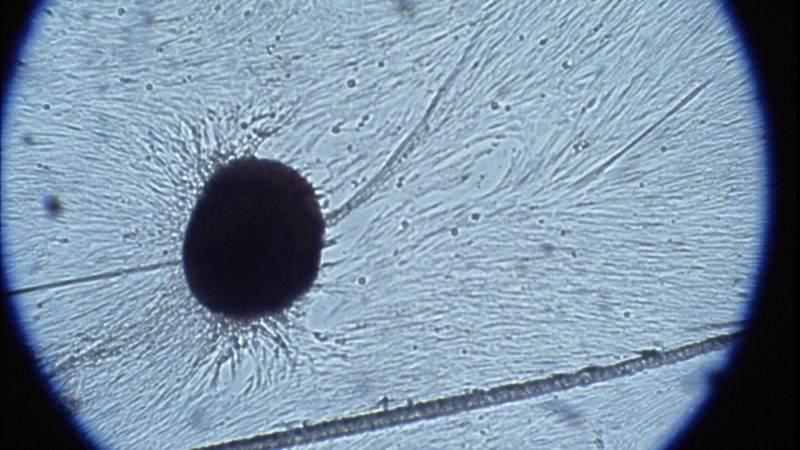

You know this one: they inject a very long, thin needle into the uterus to extract amniotic fluid and, with it, your future baby’s DNA. That terrifying needle is the only way to get the DNA, and the scientific certainty it keeps.

When my mother was pregnant with me, the risk of miscarriage from amniocentesis was considered high — one in two hundred. One pregnancy pamphlet I picked up in the doctor’s waiting room estimates that risk to be one in three hundred. Another pamphlet puts it at one in about five hundred. The geneticist says one in nine hundred. Emily Oster, whom I find more reasonably human than doctors or pamphlets, approvingly cites two “good” studies with very different conclusions: one in eight hundred, and one in sixteen hundred.

The odds themselves do not bother me, but I do not like the way they shape-shift — or, in contrast, how certain the doctor is when she tells me that everything will be fine.

The doctor’s certainty, too, is a charade. Medical certainty is a form of passing the buck. Whatever the diagnosis, it becomes our existential problem: How certain are we that we could parent a child with a disability? That we could watch our first child struggle for months and then die?

This is not, I realize, about an optimal pregnancy. It is — already — about parenting. You cannot be certain of something that you know you can’t control. And you cannot control the life you create, not even for the fleeting months it is inside your own body. You can only hope to support it, whatever odds it faces.

We opted out of the amnio, which confounded the medical team, who assumed that we simply did not understand the numbers. They reminded us how awful spinal atrophy is; I told them that my husband’s odds of carrying the gene were lower than the risk of miscarriage from amniocentesis, at least according to the literature in the waiting room.

“So you’re certain?” four different medical professionals asked me.

“Yes,” I lied, every time. “We are certain.”