Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Run Through the Jungle” blasts for the first couple of minutes in Brad’s van — yellow and, to my mind, alarmingly easy to spot — in Bakhmut, in the Donbas province, Ukraine. The salient, which is how the militarily trained describe the enemy, stands about ten kilometers from us. We are here in a frontline town waiting for a lumbering enemy who no longer even bothers sending infantry unless a place has already been battered beyond recognition from the skies. A war of artilleries. Savage, arbitrary, relentless. If it requires skill and precision, and it does, I don’t see it. The devastation is mostly a crapshoot; one building is sliced in half, while another across or next to it stands perfectly erect. Broken windows, yes. But those get fixed. The burnt schoolhouse doesn’t. Not anytime soon. And before all of this is over, Bakhmut and towns like it will cease to be the most basic thing they had been: habitable.

The town is already mostly deserted. The firehouse crew remains. Each morning, the crew sees to it that the inhabitants who are left have food to eat. Supplied by an international NGO, the large packages wrapped in white plastic remind me of whole turkeys on sale at American supermarkets before Thanksgiving.

It had, in a way, begun, at least for me, three weeks earlier, not in Ukraine but in a café across from the University of Tehran. R, a young commander of the northern resistance against the Taliban in Afghanistan, was suggesting a trip to the Hindu Kush, where the Afghan resistance barely hangs on. With a shrapnel injury to his hand, he was recovering in Iran surreptitiously, wearing an ill-fitting dark suit, his thick black hair combed carefully, yet awkwardly, to one side. The man was entirely out of place in that hip café away from combat.

“No, I cannot go to those mountains right now,” I told him.

“Why not?”

“Because I must go to Ukraine.”

He looked disappointed but did not press with the obvious question: There’s a war far closer to your home, among people who speak your language. Why do you need to chase battle in Ukraine?

Because Ukraine gets the attention that Afghanistan no longer does. I wanted to see how that worked and what it meant to me, if anything. Yet there was an element of copping out in this, I knew. One doesn’t, or shouldn’t, just get up and go check out a fire on the other side of town when the house next door is already burning. But it had been nearly a year since Kabul fell to the Taliban, and we were at an impasse with Afghanistan, all of us — those doing the fighting, like R, and those like me, working behind the scenes. There was little hope, no support from the international community, and no glimmer of a silver lining on the horizon. R was going back to Afghanistan because he was an Afghan and a fighter; he had no other option. I did.

So I’m here, across from the firehouse in Bakhmut, in a bright yellow van, with Brad. His demeanor tells me that this American has substantial military experience; he has a certain way of being on point and operational that I’ve known in many a professional soldier. Yet he won’t discuss it. He emphasizes more than once during our half day together that he gave up drinking ten years ago. It’s a point of pride. He mentions Jesus only once, and the idea of redemption in general from an elusive former life also only once. But I can’t get a good read on the most obvious questions: Why is he here? Why is he helping? Why is he risking his life like this? He could be in Ukraine doing less risky things than driving around in a loud moving target delivering food and evacuating folks from continually shelled frontline towns and villages. Or, with what I imagine to be his background, he could turn Ukraine profitable for himself. People often do in war. No one is paying him for any of this.

I ask about Iraq and Afghanistan, places he might have served. He is mum. I drop those questions. He has a job to do, after all. The medical kit he carries with him is enormous, far bigger than a typical kit, unless you’re a bona fide medic. The oxycodone is the only thing inside that might not meet regulation; it is expired by some two years. He kept it from an old dental procedure he’d had in the States, he explains. While CCR blasts from the van’s speakers, as if this were 1970 and we were in Vietnam, he says with dry irony and a stiff grin, “Where you’re about to go with me, if one of us happens to lose a limb or worse, these pills might still work for a minute.”

His words turn my attention, with abrupt nostalgia, some twenty paces away toward my accomplished travel companions: the Colombian and Spanish television news duo of Catalina and Oriol, along with their Ukrainian fixer, Orest, who is a logistics genius. Together we’ve been chasing this war and its stories, zigzagging across fields and fields of wheat and sunflowers beneath intimate blue skies. Appropriate land in an appropriately flagged country. I am occasionally envious of the trio’s sublimely poetic digital competence in their battleground coverage for their television network while I stand to the side, looking not for war’s latest news but for its oddities and quirks. And they are many. Just the day before, we ran into a man from New York who had brought his off-road bicycle to this wasted landscape and pretended to be a journalist. With the word press plastered in large letters on his flak jacket and his helmet, he went about doing wheelies in the middle of the utterly deserted streets. Given all the roadblocks and checkpoints currently in this country, I had no idea how he had managed to negotiate his way into Donbas and what he meant to eventually do with the footage from the GoPro attached to that helmet. Social media war bravado, I imagined. I resented him a little. His appearance made light of things. People were dying. People are dying.

The headlines that history will go back to again and again, rightly so, are these: the siege of Kyiv, the battle for Kharkiv, the fall of Mariupol, the indiscriminate killing of civilians in Bucha, the attack on Odesa’s harbor, the contrasts — images of ruined, burned-out buildings in the east of this sizable country with the comparative calm in far western cities like Lviv. But war is also personal, and I’ll long be remembering the suitably angel-faced Hare Krishna mother and her daughter who were waiting at the hostile Belarusian border, that inhospitable no-man’s-land, one cold and windy morning as they tried to make their way back to their native Zaporizhzhia and, essentially, to the Russian line of fire. I bought the nine-year-old girl two bars of chocolate at what might have been the last bodega on earth and watched them finally catch a ride away.

These suspended states that war imposes detach people from themselves and at the same time demand a doggedness to stay exactly as they are. It is as if losing one’s way of life, even a little bit, might mean losing the war. At a posh supermarket, the sound of sirens brings everyone inside to a standstill: escalators stop; cash registers go silent; men and women seem to float above themselves, waiting to buy or having just bought prosciutto and Camembert and Vitamin Water on their way home from work. This is a market that could be mistaken for another in, say, Paris, but it is in Dnipro, city of experienced and wannabe gangsters, always just two or so hours away from the take-your-pick front line, and tucked away in its peripheries the decrepit insanity and occasionally obscene beauty of old Soviet industrial undertakings.

I admit that I haven’t always been grateful for my American passport. Today I am. It is not a good day to display one’s Iranian identity in Ukraine, as news reports suggest that Tehran has promised the sale of several hundred combat drones to an isolated Russia with a depleted arsenal. Conversely, to be an American here is to have a part in precision US ammunition and the HIMARS rocket system — materiel that Ukraine needs more of if the country is going to have a chance to withstand or perhaps even defeat what was to have been the Russian juggernaut. Brad and I are, therefore, on the same page, by default.

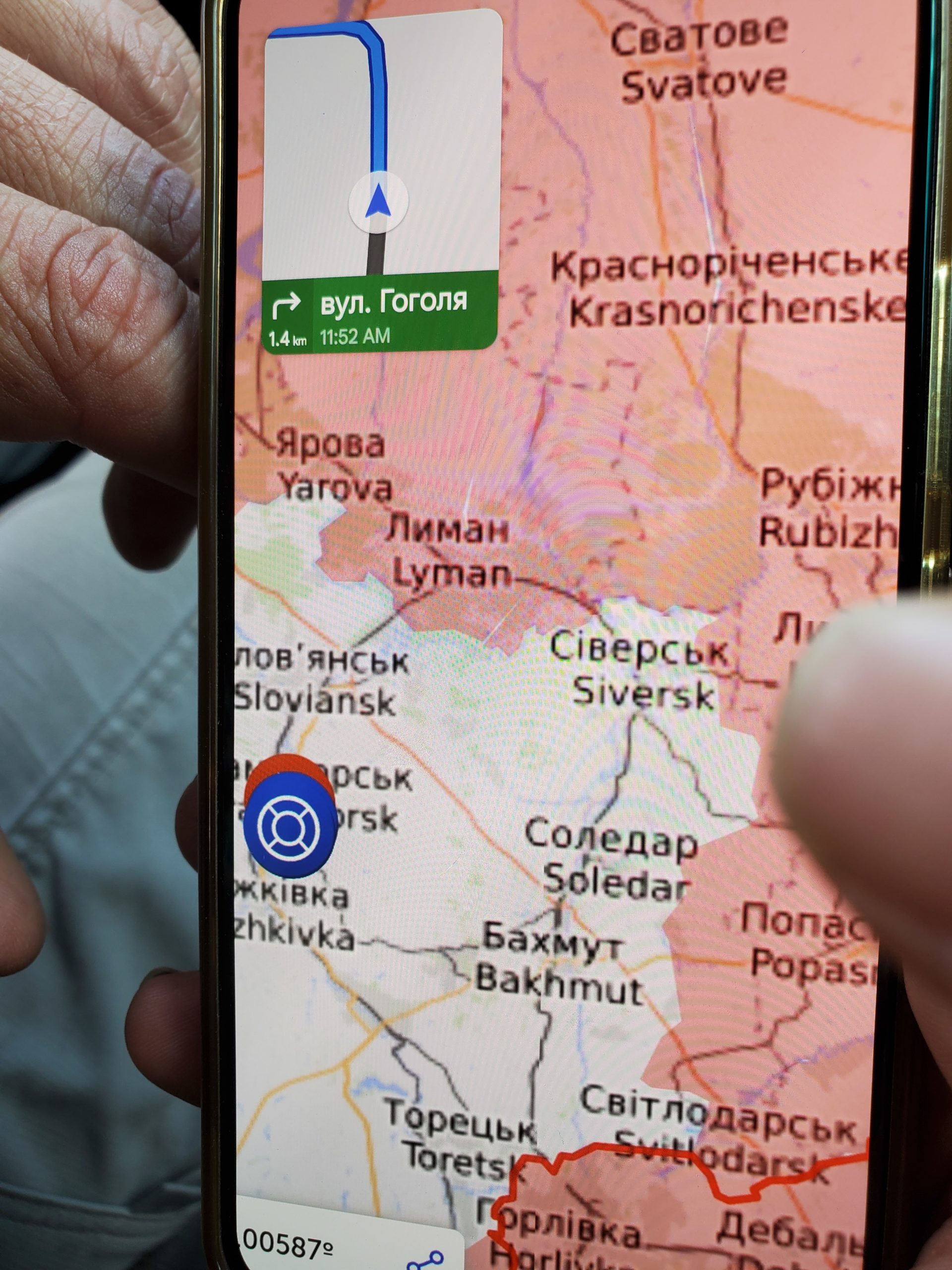

He shows me the town of Siversk on an app called the Live Universal Awareness Map. Now I see the wager: the town sits barely three kilometers from the Russian lines. Bakhmut, though under continued shelling, could have been a faraway country, a safe one, by comparison.

“And the Russians have the high ground,” he adds, without meaning to be dramatic. Brad wants me to understand that volunteering to accompany him today is no joyride in the park. I never thought it was.

He is taking — we are taking — exactly one hundred packages of donated food from Bakhmut to those who still remain in Siversk. “If there’s one thing I know how to do, it’s drive,” he says. “I’m here to drive. It’s what I can do for these people.” He can also make guitars, and at some point in his life, he spent time in New York City, driving a UPS truck in East Harlem. “Do you know what it means to drive a UPS truck in New York City?” he asks. I do. And I admire his precision and swift reflexes at the wheel, on a path filled with potholes and the fragmented waves of asphalt left behind by massive military tanks.

I leave behind preoccupations with his past, but I have to ask again: “Why do this? Was there a moment when you were sitting at home back in the States and you thought, Fuck it, I’m going to Ukraine? Or was it a decision you came to slowly?”

He came to it slowly, he admits, but ultimately it was a decision of the moment. If someone had asked me the same question about why I was here, my answer would not have been dissimilar. But the similarities end there. This American is here because, he says, “‘It has to start somewhere. It has to start sometime. What better place than here? What better time than now?’ It’s from the song by Rage Against the Machine. You’ve heard it, right?”

I say yes, but I don’t really know the song, since the band was always, like so many things in life, just a distant and mildly interesting name to me. Now, however, Rage Against the Machine and their song inflict new meaning on this Bakhmut–Siversk road in Ukraine, as do the Russian guns. During the next twenty minutes of the ride, Brad is suddenly forthcoming, even chatty, speaking rapidly and in ready quotes, as if he means to get it all in, in case we don’t make it.

He says he’s really here because of Martin Luther King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail”: Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. And because of the poetry of Stanislaw Barańczak. And Philip Larkin: Of each other, we should be kind / While there is still time. And Ilya Kaminsky and Osip Mandelstam. And the writings of historians of morals, like Anne Applebaum and Jonathan Haidt and Jonathan Rauch. Later he’ll even send me a WhatsApp message with lines from a poem by Dag Hammarskjöld, the second secretary-general of the United Nations: Tomorrow we shall meet, / Death and I — / And he shall thrust his sword / Into one who is wide awake. / But in the meantime how grievous the memory / of hours frittered away.

The scorched earth and dead trees on both sides of the road signal the adversary’s mostly clear view of us. And the closer we get to Siversk, the harder it is to continually change focus between the road and Brad’s ample reply to why he’s come to Ukraine. Here is a man who has done his homework on the subject of kindness to others, but he still props up his argument with poetry and song and philosophy in order to not come across as some do-good, unfocused softie with a big chunk of time on his hands and a bigger hero complex.

“And what’s your story?” he asks.

I want to tell him about “Dr. Shaman,” a seasoned and beloved medic in his sixties, whom we interviewed just a few days ago on the front lines near Kramatorsk. He told us he’d been a paratrooper in the Soviet Army during the invasion and occupation of Afghanistan decades earlier, and now he was fighting against the same military he had fought for so long ago. Dr. Shaman did not seem to gauge the irony of his position; he was a workhorse, a great one, and not a philosopher, which was alright by me.

But I do not tell this story, nor others from my weeks in Ukraine. Instead, as the van barrels headlong toward Siversk, I begin to tell Brad about Afghanistan, about how I believe that the never-ending war in that country is really the other end of the equation to the war now in Ukraine — the toxic but hardly last gasps of another empire, Russia, that has been for far too long sick with itself. I mean to tell him that I came to see this suffering for myself in order to shed my resentment of Ukraine for stealing the show from an Afghanistan left indifferently to bleed. And I have seen such suffering — the staggering grief of mothers and widows and fiancés inside and outside cemeteries. The easy availability of luxury chocolate and cherry-sized blueberries mere kilometers from centers of destruction does not, it turns out, lessen the reality of mourning, any mourning, nor is a death in the Hindu Kush more of a death than one in Donetsk or Kherson.

Brad, however, does not give me room to articulate much of this. Less than a minute into my spiel, he sticks the map app in my face again while the other hand stays on the wheel.

“Eleven minutes to our destination,” he says. What I understand is: From here on out, we need total focus. So let us both shut up and keep our eyes on the road and our ears listening for incoming. Not that any of it matters if an incoming has our name written on it. In fact, there was one really close incoming that made us go for the ground. It probably had my name misspelled, I’d joke to myself later on.

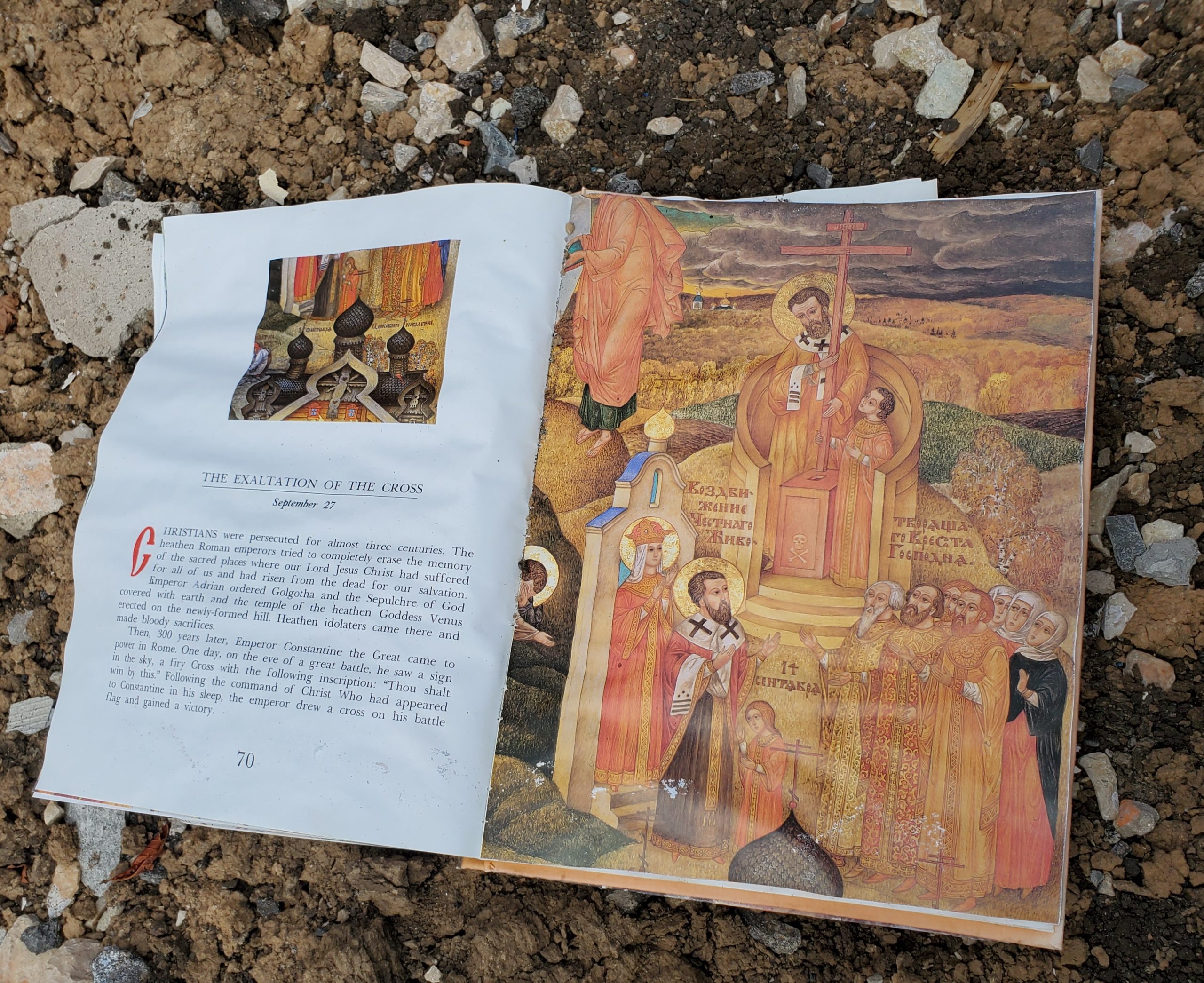

Siversk truly was the end of the world, though just one among many. The accompanying photographs are mostly of that single day from a town where folks, unlike in the movies, step unhurriedly past burn and ruin; there really is nowhere to go. Artillery battles are volleyball. There’s a square, and you are standing in it, and the ball will come your way at some point. Hurrying is of no consequence.

Into this phantasmagoric terrain, two accidental men, an American and an Iranian, succeeded on a July day in bringing food but failed at evacuating anyone from a Russian-speaking population that was, by turns, mistrustful and appreciative. The next day, I’d move on to other geographies of the war. But Brad would return to Siversk with twenty cans of petrol he had promised its stunned inhabitants. Twenty cans of petrol in the back of a yellow van that could get blown to pieces at any moment.

I’m glad to have known him, as I was glad to know Sonia (nom de guerre), a successful international litigation lawyer who had been living in France but chose to return home to Kyiv on the second day of the war and enlist. And Alex, the 23-year-old Ukrainian soldier manning none other than the celebrated Potemkin Stairs in Odesa. On checking my American passport but seeing the middle name of Mohammad and the birthplace of Iran, Alex asks, “You are Muslim?”

“Yes.”

“Born Iran?”

“Yes.”

“Come.”

Fifty or so paces back, the two of us stand watching the top of those illustrious, though hardly extraordinary, steps in the dark of the evening.

“Alex?”

“Yes?”

“Your job before war?”

“My?”

“Job. Your job.”

“Ah, job. I am MMA fighter.”

“Mixed martial arts?”

“Yes, yes. I fight.”

“Thank you, Alex. No pictures?”

“Thank you. America, thank you. You, thank you. No pictures.”