Mariana Martínez Esténs knows how journalists like a near-death experience. As a Mexican journalist who often works with foreign reporters who drop in to chase the country’s “most dangerous” stories, she also knows how reporters like to talk about those dangers. She names these tales “fireflies” — stories that become performance and anesthetic for the teller, beams of light that gather audiences and cover personal layers of fear.

In Inside People, Esténs reflects on the last decade of her work. Through vignettes about incarcerated people, documentary photographs of prison riots, and notes of confessions from women in a penitentiary — and by blending different narrative forms — she gives fuller shape to the stories about people who live in the carceral system in Mexico. Her book’s illustrations are softly affecting, and the inclusion of handwritten poetry offers a direct line between the writer and the reader. Among these, we have moments of breath: interludes that play with the act of diversion and pick up ideas which are mentioned elsewhere in the narrative.

Ultimately, Esténs rejects the dominant model of extractive journalism; instead, she analyzes her own role in it and proposes an alternative.

— Alexandra Valahu, Guernica Global Spotlights Co-Editor

Bryan Salazar

Bryan Santiago Salazar is a brick wall with a sideways smile and eyes that don’t blink. His hands are always akimbo. He partially buttons up his fitted shirt, just the last two buttons before the huge metal buckle on his belt.

He’s been in prison for nine of his eleven-year sentence. His record includes two stabbing murders that he claims were all just a big mix-up. He is married with two children and used to live in New York.

He also did time in New York. Bryan compares the two prison systems with yearning.

“Up there, you have everything you need: food, a bed; they even paid for me to go to school. Here, you have to fight to stay alive.”

Bryan is the most powerful prison coordinator. He has the most followers. He commands with just a look. People scatter to let him by.

He clearly is the owner of the most considerable wealth in this place and the magician who provides the most lavish luxuries: drugs (paint thinners and very old marijuana, unless asked for something more upscale).

Bryan smiles at me the moment I see him being scolded by Judge Yadira. He stands before me and asks if I have a husband. I can’t quite spin a lie, and he knows I don’t.

If he’s around, none of the inmates speak to me, and when I ask them something, they turn to him for permission to reply. Every morning he comes out to talk to us and asks me, “Everything okay, madre?”

When he speaks to me, he softens his tone of voice, lowers his head, and shows his shoulders like bulls do as a sign of a truce. Still, I feel his gaze piercing through me. He doesn’t blink.

Judge Yadira

Judge Yadira sports glittery clothes, short skirts, and long nails, and loves flashy handbags. She is married and the mother of two children. She spends the entire week at Drop of Sand and returns to the Capital on Friday afternoons.

She meets with some inmates daily to review their cases, convincing them to rehabilitate themselves, read, and go to church. The day I met her, she was scolding Bryan Salazar because she found one of his clubs that he’d used to beat another inmate.

“Look, Mr. Salazar,” she says to him like a mother to her child. “I’m going to ask you not to do that, please.”

Generally, inmates behave like scolded lambs. They lower their eyes and place their arms — their muscular, tattooed, and totally scarred arms — behind their backs.

“Yes, ma’am, the thing is that…” What follows is a pretext, an excuse employing a deeply adolescent logic in which nobody is responsible for anything. He was forced, he was cornered; there was no other way.

When I ask Judge Yadira if she finds it hard to spend her days with men who shout catcalls at her, she smiles with wicked satisfaction.

“We women always appreciate compliments.” Then, she laughs, throwing her body back, and adds, “As a professional and a judge, I have to keep them at bay.”

Fireflies

I immediately recognize the Ravenous Brit’s motives when I learn he wants to enter the bartolinas. He’s looking for stories, anecdotes that journalists pin to our chests as subtle badges of honor reminiscent of the recognition received as children: “You’re so brave. You did it all by yourself. You’re no crybaby. Never let them see you cry.” I get it.

Those comments nourished that scared little girl while she threw herself into the deep end of the pool, over and over, until she forgot how to panic. She got used to the delightful feeling of sedation that adrenaline produced during the fall.

I’ve been there.

We display anecdotes of cunning, adrenaline, survival, and mettle as bright, shiny treasures or fireflies we release from our hands to illuminate the basements where we seek refuge from gunfire or the rain-soaked tents during a jungle storm.

We tell them to block every feeling and to be deafened by the applause of others.

That light emanating from the anecdotes is an anesthetic, a coating that we smear like wax on our fruit-like skin. The coating prevents our fragility from leaking out and moisture, sadness, and fear from seeping in.

Only then, anointed like shiny supermarket fruit, are we able to do our job.

That’s why we continue to take risks, to fuel the cycle: fear, survival, coating, anesthesia, fear. More fear, more survival, and more layers of coating infuse our sense of humor with darkness.

The fireflies of each survival anecdote are released by opening our hands. Opening our mouths sanctions our wit — an ever-accommodating inner puppet — to dance around.

Anecdotes are told with laughter, with nonchalance, over a bottle of booze, preferably in some country where its very existence is a transgression.

The coating pairs well with alcohol, tobacco, and drugs that harden the wax; they captivate and preserve us.

I recognize the modus operandi of the Ravenous Brit all too well.

The Ravenous Brit

In the hotel restaurant, he orders steak spicy sausage, French fries, and pasta Alfredo. He orders three beers with dinner. We sit at opposite sides of the table every evening. He tells anecdotes, and I see him searching my eyes for a reaction to the fireflies he releases.

“I used to direct this drug bust series, you know? All over the world, I would be with Interpol, and they would let me film drugs, pedophiles, sex rings, trafficking, neo-Nazis…”

He looks at me. I opt for evasion and stick to my tuna salad and pineapple juice.

“Granted, never in prisons and never in Latin America, but I know my way around, you know? I’ve earned this…I have so earned this.”

Whether you’ve earned it or not, you keep putting us all at risk. Tuna and pineapple juice. You are such an asshole. If I were 25, like the Efficient Englishwoman, I would be in his face arguing against his disgusting ethics that he should absolutely not be boasting about. But I have no desire, strength, or will. My will is worn out thanks to guys like him. It’s all the same to me. If I die, I die. I’ve sure earned it.

I’m glad I’m not the director of this fiasco. I’m also glad to see him explaining himself to me.

“They said you were the best, you know? I’m the best too. I know what I want and how to get it.”

“I’ll have another pineapple juice, please…”

…

Hot Potato

One thing Drop of Sand does have, is a signal-blocking tower that forces people to go to the corner of the soccer field to talk on the phone.

Clearly, there are cell phones inside, and of course, someone is using them. But not everyone in Drop of Sand can afford to make cell phone calls. They’ve devised another way of getting messages in and out of the prison. It requires the complicity of the female inmates, the guards, and the villagers who live outside the prison.

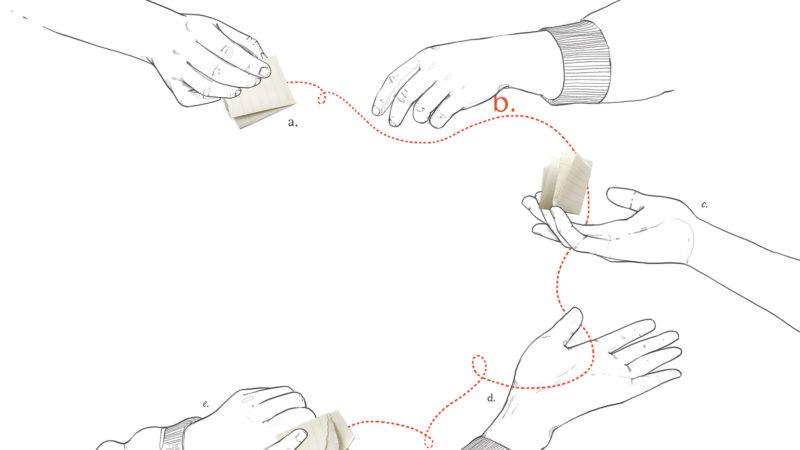

The system is called Hot Potato. It consists of handing a small piece of paper with a written message to someone and repeating the name of the recipient until it arrives in the right hands. Most of the notes reach their intended destination and get a response in less than an hour.

Every day in Drop of Sand, the bustle is like an anthill. The constant flow of hot potatoes mixes with the continuous river of dishes, sodas, food, boxes, chickens, and tools that run seamlessly through the veins of this living organism.

Using the hot potato system, Claudia asks someone to call a taxi driver to pick her mom up at her house and bring her to visit. Claudia misses her mother and four-year-old son very much. She can usually handle it, but today she woke up really sad and wants them to bring her son for a visit. It’s the only thing that makes her feel better.

Claudia and Lola

Claudia has clay skin and straight obsidian hair. She was born here in the village of Drop of Sand but later moved to the Capital because she was in love. One day, her boyfriend asked her to pick up some money, and Claudia agreed. She was arrested right there, on the spot, in the shopping center where she went to exchange the money order made out to her name, which came as a ransom payment.

She’s been in prison for two years. Her four-year-old boy is now being raised by his grandmother.

Claudia spent her first year in prison in Nahara with 400 other female inmates. She had to bunk with eighteen gang members. She had to be constantly vigilant, so she didn’t get a single peaceful night of sleep that year. She requested and got her transfer to Drop of Sand.

Upon arrival, Claudia slept for two days in a row, the best of her life. She cleans the offices at six in the morning, at noon, and at five in the afternoon. She makes tortillas and salsa, and when the cook is ill, she cooks for the guards. In the cell shared by the twelve women in this prison lives Lola, a green parakeet that the women caught one day when it came into the cell.

Claudia tamed Lola by giving her soaked tortillas. Claudia and Lola are inseparable. Every day, Lola perches on Claudia’s shoulder while she makes tortillas. When Claudia is washing dishes, she gets Lola wet on purpose. Lola gets upset and hides under a closet used as a cupboard. To improve Lola’s mood, Claudia sprinkles a trail of ground corn on the floor that ends up buying her forgiveness.

Claudia is the darling of Clase Aponte, who is at least twenty years her senior. Aponte lets Claudia use the hot potato system to bring her mother and son to see her.

“I just love tortillas, you know,” Aponte says, laughing and fixing his gaze on Claudia’s round buttocks.

Maturano and His Other Self

Otilio Álvez Maturano, aka The Russian, is a blond man with a shaved head who is 40 centimeters taller than any other prisoner — except for Bryan. He doesn’t live with the general population, nor in cell 22, where 125 rapists are kept.

The guards say he is overly aggressive. He attacks and bites.

He lives in a closet for cleaning supplies. The door opens to the outside of the prison, so now there are bars there. He comes out of the gloomy closet with damp walls to talk to me and sits on a red bucket with his hands through the bars.

“This is a mistake, pretty lady. I’ve been here for two years because of my personal business; do you understand me? I have a seven-year-old daughter and a wife, and they are not better off with me in here. Do you understand me?”

He’s here for domestic violence. He beat his wife until her skull and ribs were cracked. She — finally — filed charges and refused to withdraw her testimony. He was given a very long sentence.

“What did she get out of it? Now, she’s a single mom, and my little girl doesn’t have a dad. What did she get out of it? All she got was to destroy a beautiful family.”

The next day, I stop by to see Maturano again, and he is a completely different person. He’s sitting on the red bucket again and puts his hands through the bars, but he changes his story and, to my surprise, only speaks to me in English. He is a totally different person.

“I lived in Brooklyn for the longest time, honey baby, but then I made a couple of mistakes, you know? I’m human, so I was in prison there, got sent back to this fuckin’ place I didn’t even remember.”

I ask him his name, and he shows me pain. He cannot access the memory of his name. He frowns as if the truth is quickly escaping him as if he wants to catch a butterfly rising up outside of these walls to go deep into the jungle.

He becomes agitated as he speaks and begins to bang his head against the bars, cutting and bleeding from his brow. Juan sees me from a distance and shakes his head as if saying, journalists are all crazy, for reals.

Rafael, The Teacher

Rafael is sixty-three years old, and everyone here calls him “the Teacher.” He’s in for two murders and clearly says that, truthfully, “yes to one; no to the other.” He was a rural teacher and got involved in politics with ideas that were pretty leftist for this country. He is cultured, informed, serene.

“I did kill a soldier trained by the Chilean military under Pinochet. He came to kill about 200 men, including my father. They should have thanked me for taking out the trash. My enemies pinned the other one on me because they were just tired of me making so much noise.”

Since there is a price on his head, he lives in a tiny separate room next to Maturano’s cell. His cell is painted light blue. A hammock hangs outside — so clean, it shines. His cell is a haven of peace and pale colors.

He has a carpenter’s workshop where he makes toys for children, tables, chairs, and whatever people in town or inside request.

Today he’s putting the finishing touches on a blue and red helicopter he hopes to sell on visitation day.

Visitation

Drop of Sand has a visitation protocol. Visitors are handed wooden chips with numbers written in marker. They’re just like the ones guards use to keep track of pool scores. Guards write down the names of the visitors in a notebook that regularly gets soaked in soda, so the pages are all wavy and covered with flies. There are no X-rays, no dogs, no searches, no random checks. The doors get locks with padlocks from the hardware store, and more than a few inmates have keys. Who has a key? No one knows.

Female guards conduct searches because the majority of the visitors are women with children, many children. The guards barely glance into the bags full of stuff that the visitors carry in. They seem to open the bags more out of curiosity than protocol. That one has beans and tamales; this other one has talcum powder, towels, and socks.

Rosario is a skinny, spindly young woman with big eyes. She started coming to visit her uncle, but then she fell in love. Today Rosario wants to pay a conjugal visit to a prisoner she met during visitation. She smells of sweets, and her eyelashes are spectacular.

Wood from the hardware store arrives addressed to one of the inmates, and the owner of a tractor enters to have Hernán, the mechanic, check the engine.

My Ritual

Every afternoon when I arrive at the hotel, I take off my clothes at the entrance to the room and pile them on the floor. I get in the shower, and only there:

I breathe, I feel, I release,

I bury the day of stories as they go down the drain.

Then, with clean clothes and wet hair, I go out to the hammock in the courtyard to write, and only after I’ve released everything I’ve experienced do I approach the bed. I turn on the TV for background noise. I can only watch movies with dragons and The Pink Panther.

Excerpted from Inside People by Mariana Martínez Esténs. Published by Pomegranate & Fig LLC.