In 2017, just one year after Donald Trump was elected president, Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism sold out on Amazon as it improbably reached #4 on its bestseller list — seventy years after its original publication date. Yet in her new book on Arendt, Samantha Rose Hill warns us that the renowned philosopher would not have wanted us to look to her political writings as an analogy for what’s happening today. “She was not a feminist, a Marxist, a liberal, a conservative, Democrat or Republican,” Hill writes. Arendt would have been very uncomfortable being placed in any political group.

In Hannah Arendt, Hill explains that Arendt was more interested in the process of thought — of reconciling ourselves to the world so that we can properly deal with it — than in articulating transcendent truths (which, according to her, did not exist). Along the way, Hill illuminates a warmer, more personal side of Arendt than we’ve seen in op-eds and think pieces over the past few years. It’s an image that complicates the idea of Arendt as an unsentimental thinker, which I came to know during my time in academic philosophy. I asked Hill to share some of the images she looked to in crafting her portrait of Arendt, revealing a person who did not believe in progress and was not a utopian thinker, but wrote impassioned poetry and loved to shop.

—Regan Penaluna for Guernica

1. “She liked to wear Ferragamo shoes and had a manicure every two weeks.”

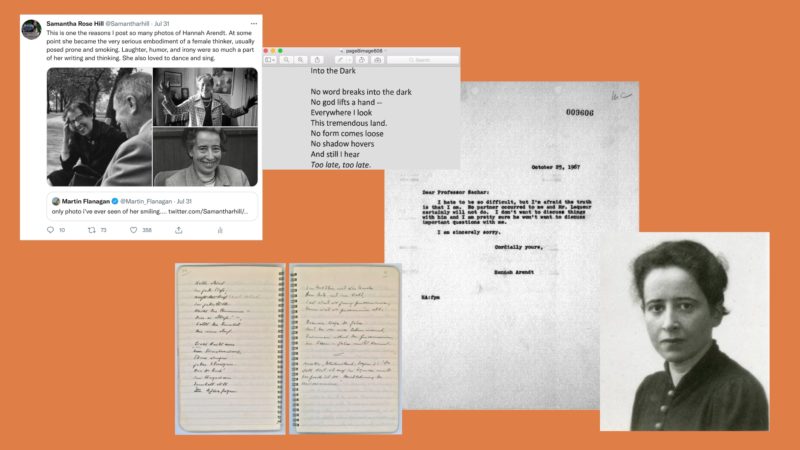

Guernica: You use Twitter to amplify an alternative vision of Arendt, and I love these photos you tweeted of her laughing and smiling. She has such joie de vivre here. Tell me more about why you shared these images.

Samantha Rose Hill: My hope is to change the way people engage with Hannah Arendt’s life and work. In the public imagination, there’s this very serious view of Arendt in black and white, chain smoking, bent over a table, and talking about evil and Nazism. But in the archive, you start to see that she was a person. She liked to wear Ferragamo shoes and had a manicure every two weeks. She threw incredible parties, and her favorite drink was Campari and soda. She spent Sunday afternoons calling everyone she knew. She traveled across the country constantly. Relationships and friendships were important to her. Humanizing a figure like Hannah Arendt makes her accessible to a wider audience. I would love it if more young adults were reading Hannah Arendt.

Guernica: Why?

Hill: Arendt was fiercely independent. She was a rebel from an early age. She was kicked out of high school for leading a protest against a teacher who had offended her; later, after Bertolt Brecht’s address book was confiscated, she turned her apartment in Berlin into an underground stop to help communists escape the war. In 1940 she was part of a mass escape from an internment camp with 62 other women. Arendt embraced being an outsider and argued that it’s important to cultivate who you are and not just what you are, which is given by birth. She was hungry for life and experience, and she acted courageously when she was faced with difficult decisions. In our era, which is so defined by technology, Arendt’s life and work exemplify the importance of human, face-to-face interactions, critical thinking, personal responsibility, and political action. With social media today, where everything is so easily reduced to appearances, Arendt’s work draws us back to the world of experience, where we exist side-by-side, together.

Guernica: Around 70 percent of Americans use social media today. What do you think Arendt would say about that?

Hill: In the 1960s, Arendt was worried about the effect television was going to have on the future of American politics. She anticipated the rise of televised debates alongside the decline of American political parties, with the rise of party machinery. This was not the popular argument among political scientists at the time, but I think it was quite prescient. That was television. Today we’ve seen what Arendt called, in The Human Condition, the triumph of the social, and what she describes as the loss of distinction between public and private life.

That is, we are constantly publicizing our private lives, and there’s not much difference between news and entertainment. Everything, from our dinner to political candidates, are fodder for social media marketing. Shortly before Trump left office, he said that he wouldn’t have won without Twitter, and that’s probably the most honest thing he said in four years. When we lose the distinction between public and private life, we lose the realm of solitude necessary for self-reflective thinking, and we also lose sight of how our private lives are being politicized by external forces. Which is to say, not everything is inherently political, but many things, if not most, are politicized. What this added up to for Arendt was a loss of judgment.

Guernica: In your book, you discuss how Arendt’s thought has been warped or misunderstood. What do we get wrong about Arendt’s thinking?

Hill: When she died in 1975 at the age of 69, she was mostly known for her reportage on the trial of Adolf Eichmann. I think her work on the banality of evil is fascinating, but she also wrote in other texts, like Men in Dark Times, which isn’t read as much, about thinking, love, and friendship, and how we should act ethically when we are confronted with impossible situations. Then in 1982, she was back in the popular imagination, this time as Heidegger’s lover, after her first biographer shared her discovery of their covert romance. Arendt met Heidegger in the fall of 1924 when she went to study with him at the University of Marburg. She was 18 and he was 35 and married with two kids. When she learned of his Nazi activities, she broke all ties with him until 1950, after the war. But I don’t think focusing on her romantic entanglements is the best way to engage her life and work.

More recently, when Trump was elected in 2016, Arendt’s work began to resonate with an entirely new audience. People turned to Arendt in this incredible moment of flux to try and understand the rise of populism and Trumpism in the United States. But I think Arendt would have been very wary of her work being used as an analogy to understand our present political conditions.

Guernica: Why is this?

Hill: Arendt was very anti-ideological. She would have resisted being called a Republican, a Democrat, a liberal, a progressive, a Marxist, a Communist, a feminist, and so on. She was weary of these kinds of categorizations, and she avoided this kind of self-naming. She didn’t think we could understand the world through any kind of fixed, procrustean frame.

At the end of the preface to The Human Condition, she says that we have to “stop and think what we’re doing.” Arendt’s axiom demands that we constantly rethink the world anew from the vantage point of our newest experiences and fears, which have changed a lot since she was alive. We can’t rely on fixed frameworks to understand our world today. Our world has been dramatically changed by the Cold War, the War on Terror, the rise of technology and social media, to name a few things. Arendt was never writing to get to the truth of something or to give an epistemological record. It was more about doing the work of understanding so that we can reconcile ourselves to the world that we live in, and act responsibly when it comes to what is happening in front of us. She was skeptical of any kind of transcendental thinking that turned one away from the world of experience toward a philosophical realm of pure speculation, or utopian thinking. She didn’t believe this kind of thinking, so far removed from everyday experience, could help us navigate the political crises we’re dealing with, which are always changing. In this way Arendt has more to teach us about how we think about politics than what we should think about politics.

Guernica: This reminds me of Arendt’s theory of love: that loving the world is synonymous with accepting it. It’s a crucial condition for doing politics and philosophy.

Hill: Arendt talks about love in a few different ways. In The Human Condition, she talks about romantic love as the love that turns two people away from the world. It is anti-political because as the lovers are enveloped in one another, they become preoccupied with themselves. But her most discussed concept of love is amor mundi, which in Latin means “love of the world.” The concept comes out of her early work on her dissertation about love and St. Augustine. In his idea of caritas, or neighborly love, she saw a way of loving the world, of being with others while attending to the world. I always think about Arendt as if she’s planting our feet on the earth, trying to get us to deal with what’s in front of us — the good and the bad. We don’t get to choose. It’s not an easy task, though. In a letter to Karl Jaspers, she writes “What is most difficult is to love the world as it is, with all the evil and suffering in it.”

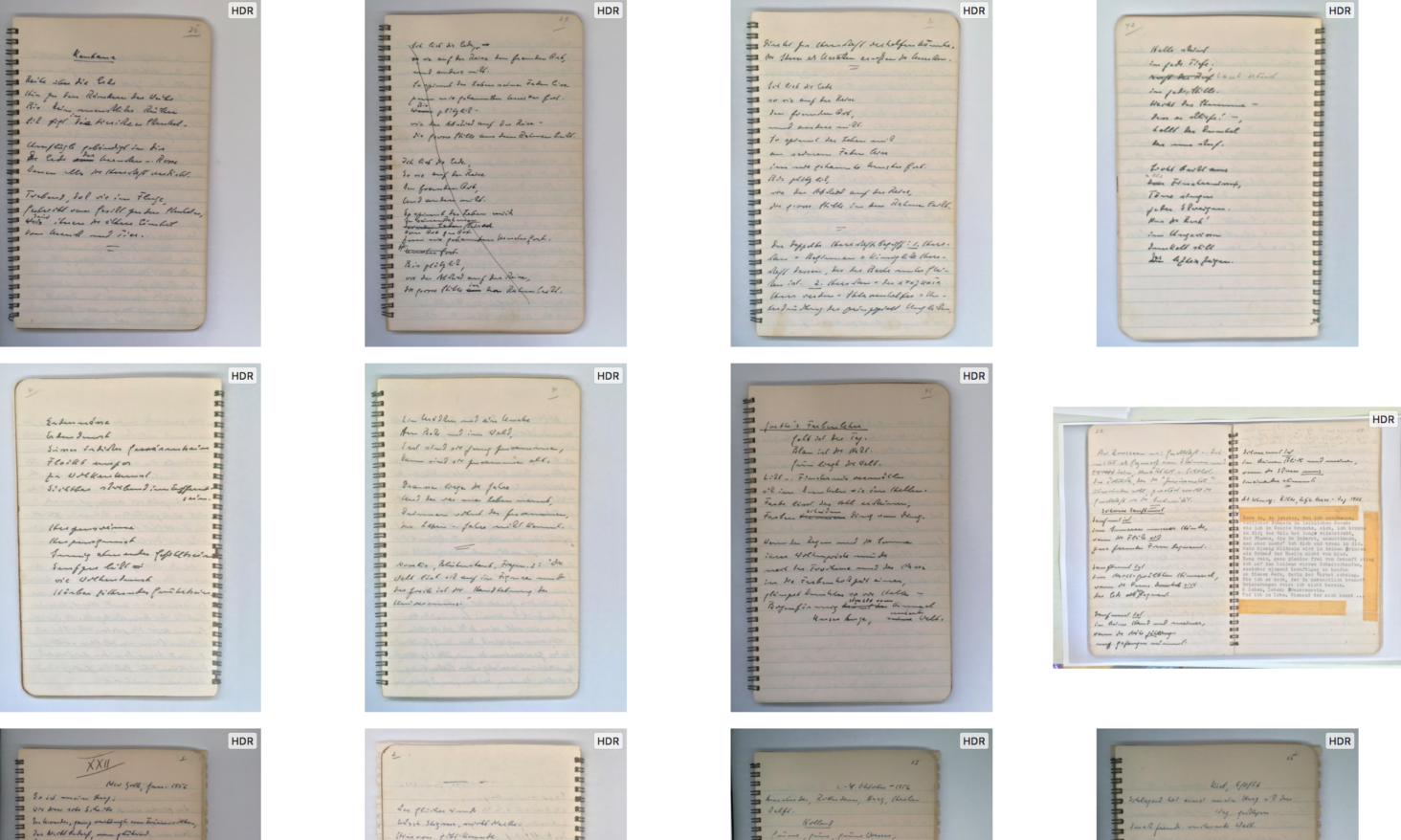

2. “Seeing Arendt’s notebooks in person completely changed the way I think about her work.”

Guernica: When you accessed her notebooks in the archive, you said you’d gained a deeper insight into the process of Arendt’s thought. What did that look like?

Hill: I had the opportunity to visit the German Literature Archive in Marbach, Germany while I was writing the biography. The head of the library let me handle Arendt’s notebooks, which was such a treat. He brought them to me completely disordered in a bursting banker’s box. I spent an entire week with them, reading, taking notes, making facsimiles. Seeing Arendt’s notebooks in person completely changed the way I think about her work. I didn’t realize how spatial a thinker she was. It’s one thing to read a passage in which she says, “Thinking is the two-in-one conversation that I have with myself. When I retreat into the realm of solitude, I split up into the two of one and I keep company with myself.” In her notebooks, you can see Arendt thinking in dialogue across the page. Her colorful, spiral notebooks are full of hand edits, crossed out poems, and newspaper clippings in five different languages. I realized she was using the space of the page to curate conversations between different thinkers, juxtaposing quotations, passages, and thoughts. She uses montage, for example, to bring an Emily Dickinson poem and the topic of homelessness into dialogue, to think about the burdens we carry with us through the world. This is completely lost in the Denktagebuch, which reproduces the notebooks in black and white, with none of the texture or nuance of the actual notebooks.

Guernica: I was surprised to learn in your book that Arendt didn’t believe in progress and that she rejected utopian thinking. It sounds depressing. I wonder what motivated these ideas.

Hill: When she was at the Partisan Review, she was still writing in German and being translated into English. At one point while she was going through the translation of an article she’d written in German with the editors, she noticed they had slipped in the word “progress.” She said, “What? I never said this word — get it out.” The men excused themselves from the room and closed the door, and she heard them whisper: “She doesn’t even believe in progress!”

Arendt was very skeptical of progress. She shared this view with Walter Benjamin, who had been a very close friend of hers. Arendt saw the history of the Enlightenment as entangled with the history of barbarism: How did the promise of progress, of science and technology in modernity, not lead to freedom and liberation, but to death camps? This was and still is a very divisive argument. Some people look at the history of progress or liberalism and democracy as entirely separate from the history of fascism and totalitarianism and right-wing populism. Arendt sees the history of progress and democracy as entwined with the history of fascism and totalitarianism. Totalitarianism might disappear from the world, but elements of it remain. At the end of Origins, Arendt writes: “Totalitarian solutions may well survive the fall of totalitarian regimes in the form of strong temptations which will come up whenever it seems impossible to alleviate political, social, or economic misery in a manner worthy of man.”

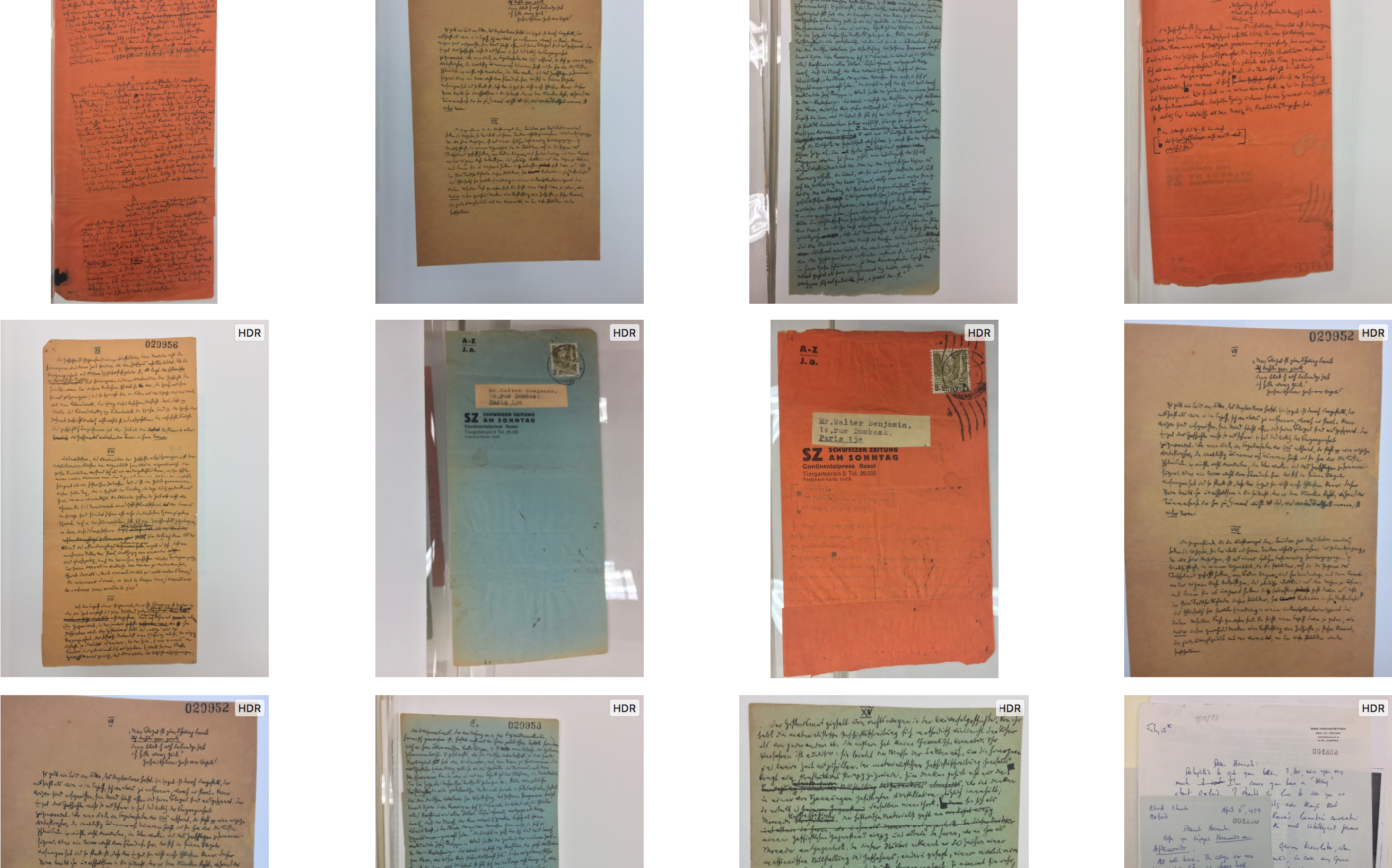

3. “When you’re holding them, you experience what Benjamin might have called the aura of the object.”

Guernica: Speaking of Benjamin, you shared this image of his notebooks. Can you tell us more about them?

Hill: When Hannah Arendt and Walter Benjamin parted ways in Marseille, just days before he committed suicide while trying to escape through the Pyrenees, he entrusted her with a suitcase of his final works, including the Theses on the Philosophy of History. He called them “a bouquet of whispering grasses.” I wish the library would put them on display so the public could see them. They are a magnificent work of art. I sat with them for an entire day, not wanting to leave the library. When you’re holding them, you experience what Benjamin might have called the aura of the object. The presence of the Theses, their history, where they exist in time and space — they are a phenomenal historical artifact.

4. “She would lay on her couch and smoke and think.”

Guernica: Here is a 1933 passport photo of Arendt you shared with me that I had never seen before. Why did you select this image?

Hill: It’s my favorite image of Arendt. She looks so fierce — she’s staring straight into the camera, and there’s a hint of a smile and a snarl. Her dark curly hair is tied back and wispy. You can see her passion for life and her hunger for understanding. She’s wearing a black button-down dress that appears in another photo of her, taken years before, while she’s smoking and leaning against a wall. But in her passport photo she’s aged, and you see the politics on her face. The photo was taken right before she was arrested by the Gestapo for conducting antifascist research in the Prussian State Library. The Gestapo held her for eight days, after which she fled with her mother through Prague, to Switzerland, and finally Paris where she lived for the next eight and a half years, working.

Guernica: We know Arendt today primarily through her writings, yet you describe her as being a professional writer by accident. What do you mean by this?

Hill: She was a philosopher, and almost without question would have had a very successful philosophy career as a professor in a German university had she not been forced to flee from the Nazis. She was also disgusted by the German academics she saw going along with the Nazification of academic, political, cultural institutions. She said, “I want nothing more to do with intellectuals,” and she broke with academic philosophy. She also broke with Heidegger. She decided she wanted to do only political, practical, and Jewish work. So she left academia, and worked for several Zionist organizations helping Jewish youth prepare for emigration to Palestine.

When she came to the United States, she worked as a housekeeper in Massachusetts to learn English and then she went to Columbia University and started getting jobs writing and working in the New York literary world. This is also when she started writing her first major work, The Origins of Totalitarianism. She wanted to understand what had happened.

For Arendt, writing was a part of the process of understanding. She had to think and write to understand. She described her writing process as taking dictation from herself. She would lay on her couch and smoke and think and once she had worked the piece out in her head, she would go to her typewriter and write.

5. “She was melancholy from an early age.”

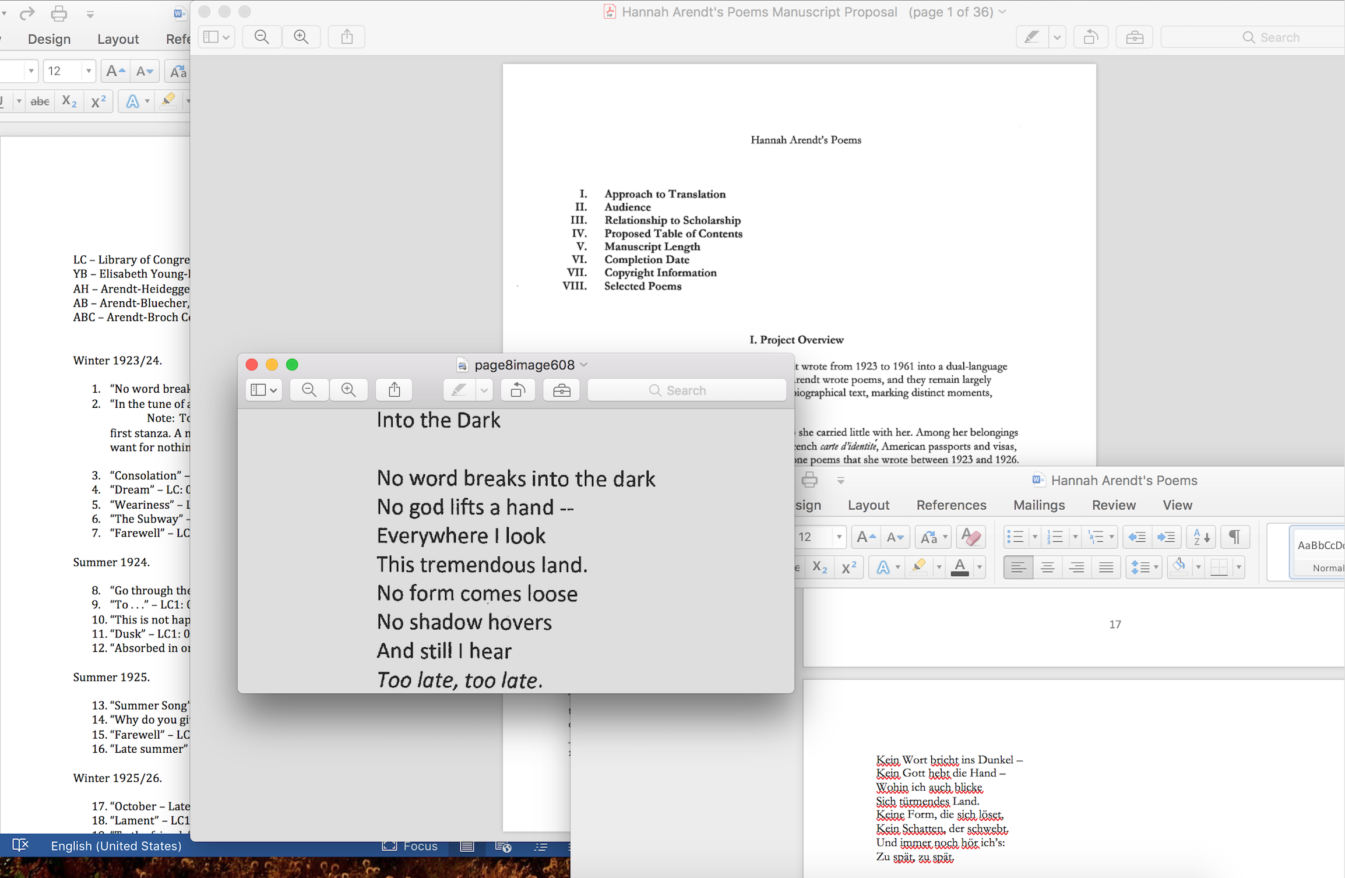

Guernica: I was surprised to learn that Arendt was a poet. Were you also surprised, or did you know this about her early on in your research?

Hill: No, I didn’t know it from the get-go. The first time I went to Hannah Arendt’s archive was in 2010, and I spent almost a year there working through her papers. Eventually I came to the last folder, which is titled “Poems: Miscellany” and inside it was a collection of poems and a short story in German. I was blown away by the fact that she had written poems. I started translating them. It’s been a long process, but they have finally found a home with Liveright. She wrote 74 poems, dating from 1923-24, when she went to study with Martin Heidegger. A lot of the early poems were enclosed in love letters to Heidegger. From his correspondence, we know that he wrote her poems as well. The poem I shared with you is titled “Into the Dark,” and it is the first poem that we have. The themes of melancholy and darkness appear throughout the poems — in fact, “darkness” and “void” are the two most often repeated words. She was melancholy from an early age, and there is a kind of poetic melancholy that courses through her writing, especially after the war.

But I still don’t really think of Arendt as a poet. I extend to her the same compliment that she gave to Walter Benjamin, which is that she was a poetic thinker without being a poet. In some of her later poems, we see her working through ideas and language that become a part of other works like The Human Condition. In fact, there are two poems that appear almost verbatim in prose form in that work.

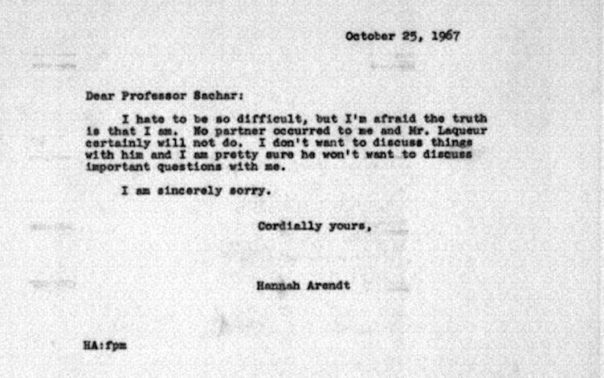

6. “She wasn’t afraid of disagreement, but she had no tolerance for bad faith.”

Guernica: Here is a letter you shared that Arendt wrote refusing to speak with the historian Walter Laqueur after he called her an “amateur historian.” What insight does this letter give us into Arendt?

Hill: I love this letter for a few reasons. There are some who would uphold Arendt as the great defender of the “you have to talk to everybody” free speech. But on more than one occasion she refused to engage in conversation when she knew it would not lead to a nourishing exchange. She wasn’t afraid of disagreement, but she had no tolerance for bad faith. For Arendt, conversation is the heart of politics. We disclose who we are through speech and action. I also love this letter because it’s an example of how she was difficult and she owned it. She wasn’t afraid to say, “No.”

7. “I told him I had to kill my best friend.”

Guernica: Tell me about this photo of your desk and the archive boxes.

Hill: As I write, I archive. I need to write and read on paper. Touch is very important to me. So I end up with a lot of physical materials. When I write by hand, or hold a book in my hands, I am totally immersed. Sometimes I get so completely lost in what I am doing, I startle if someone interrupts me because I forget where I am. This can be quite inconvenient since I like to read and write in cafes. When I was finishing the biography, I was sitting in a coffee shop in New York City crying like mad, and when I looked up the man sitting next to me asked if I was okay. I was so startled to see another person. I told him I had to kill my best friend: I fell in love with Arendt 20 years ago. It’s been a long romance, but writing this biography, I had to finally let go. And now that the book has finally appeared in the world, I wish I could have it back to write all over again.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misidentified the historian with whom Arendt refused to speak. We regret the error.