Ava, the grief-stricken protagonist of Laura Blackett and Eve Gleichman’s novel The Very Nice Box, is an engineer at STÄDA — a kind of Ikea/Muji hybrid that produces everything from forks and spoons to couches. She’s determined to bury herself in work, until a disarming, perhaps suspiciously eager young guy named Mat Putnam joins the company and throws Ava’s carefully ordered world into upheaval.

The Very Nice Box is a story of love, trauma, deception, and minimalist design. And while Blackett and Gleichman initially set out to write a suspense novel, the book is a satisfying mix of genres and tones. A queer Brooklyn office novel that winks knowingly at its cultural milieu, the book ratchets up tension through romance and satire to deliver twists that feel shocking — and then, gratifyingly, inevitable.

Despite its main character’s isolation, it’s also a story of friendship, and the product of one. Gleichman, a short story writer with an MFA, and Blackett, a hobbyist woodworker with a day job in tech, brought different styles and strengths to their collaboration. To write and revise the book, they had to be flexible and renounce ownership of particular ideas, a process that benefited from what Blackett calls their “compatible egos.” As they describe it, the experience of writing The Very Nice Box was one of pleasurable problem solving, not unlike the feeling Ava gets from working on her own design projects. The first book for both writers, Blackett and Gleichman are already at work on their second novel together.

Note: This interview contains some spoilers.

— Eryn Loeb for Guernica

Guernica: The book’s voice is so clear and cohesive, which seems like a real feat for something written by two people. How did you approach the writing? Did the way you worked together change as you went along?

Laura Blackett: In the first draft, we alternated writing chapters. We would get together for dinner every other week or so and try to outline three to five chapters ahead, and use that to guide us. But we would always stray from the outline, and a lot of ideas and details emerged spontaneously from one of us when it was our turn writing. At this point, the book has been revised so much, and undergone so much surgery, that the chapter-by-chapter alternation doesn’t really hold.

Eve Gleichman: Initially, it was really clear who wrote which chapter. While Laura was working on her chapter, I would be sanding down the previous ones to make them sound more uniform. In order for me to write forward, what already exists has to be pretty polished, so I wasn’t really able to write a new chapter if I felt like the voice was all over the place in the previous chapters. I would spend many hours just trying to even out the sentences so that they felt like one voice.

Blackett: I think I felt more comfortable forging ahead. I sort of see myself as moving around larger pieces, and Eve coming in and finishing — making things smooth, hiding the seams.

Gleichman: I love revision. That’s the most comfortable place for me to be.

Blackett: The chapters we wrote as we got to the end of the book changed much less than the chapters we wrote at the beginning. At a certain point, the book had a strong enough voice that it was easier to write to that, and the further along we got, the more consistent we were.

Gleichman: It’s partly because we knew the characters better. But we also knew where the book was headed, so it was a lot less baggy. We weren’t fooling around; we had the vanishing point that we were writing toward, so I think the book got more efficient and less shaggy.

Guernica: Early on, what was different about your approaches to writing that made the chapters feel so distinct?

Blackett: I think that Eve is an incredible craftsperson. They have a fiction MFA and I don’t come from that background, and so for me, the metaphors that Eve was using and everything else they turned out felt really polished to me.

Gleichman: I think that Laura is just more generative. Her chapters would be longer in general; they would just be more raw and funny. I think she’s less neurotic as a writer, she’s got her job to do of getting us from point A to point B to the end of the chapter, and she does it. It was such a joy to get Laura’s chapters, in part because it was such fun reading and I got to see what all the characters were doing but also because it was like: I get to revise this. I love to revise so much, so it felt like this perfect hunk of marble to sculpt before I got to my chapter. I think that’s part of what works about our writing relationship.

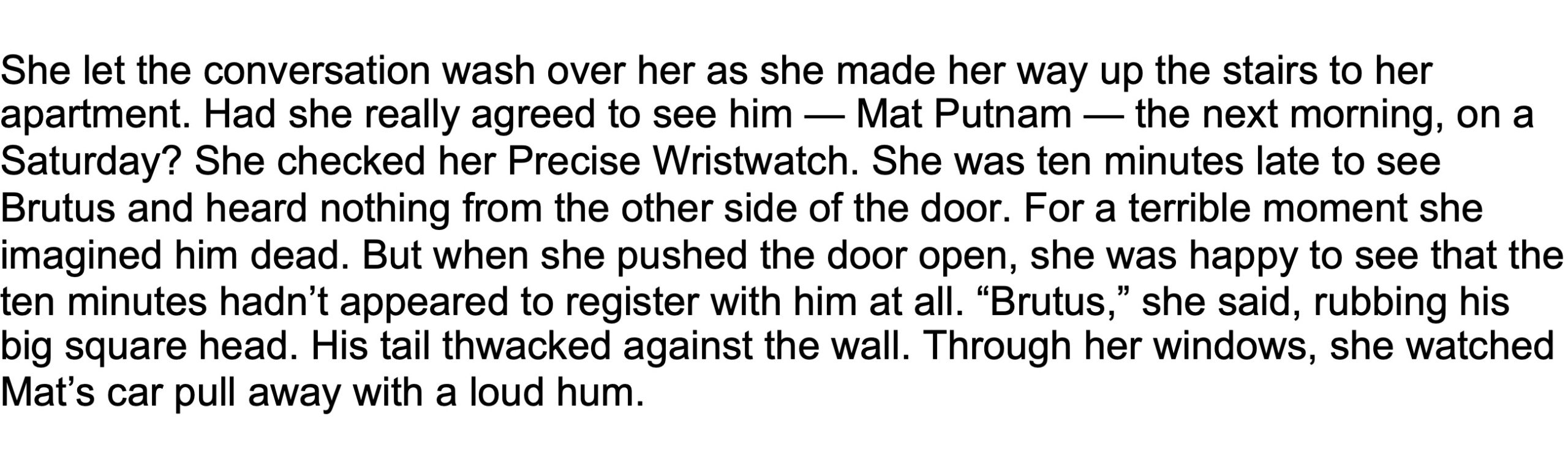

Guernica: Let’s look at this revision. What do you see when you look at these two versions side by side? What informed the changes you made, and what do you think of the differences?

Blackett: Reading them over, it’s sort of hard to take them both in. My brain wants to make them the same thing.

Gleichman: If I read these two side-by-side I would definitely know which one was the better paragraph. What I’m trying to figure out first is why we swapped the first and second sentences. There were certain times when we were revising the book when I would revise a sentence, then put it back how it was, then revise it again and then finally Laura would be like…

Blackett: I would be like, you good? [Laughter]

Gleichman: Looking at the first two sentences, what I think happened here is that I wanted to put Ava in motion, to put her in time and place. Starting with “Had she really agreed to see him, Mat Putnam, on a Saturday” is too abstract for the start of the paragraph because you don’t know where she is physically. Swapping it, she’s walking up the stairs to her apartment as she’s having the thought that follows. One of the hardest things in this book, and I think any book, was making people go places. You don’t want people to feel like Sims: She walked to the refrigerator. She walked to the door. So this was a way to make her journey into her apartment invisible.

Blackett: In the next line, we added the branding of the wristwatch, the Precise Wristwatch, which is something that we did to a lot of the objects in the book in revision. The branding is everywhere. We wanted to make everything a little bit punched up. We always talked about making it a little Technicolor; we wanted it to be a really clear and specific world.

Gleichman: Especially with this watch, which is really important to Ava. We never really referred to household objects by their generic names. This is one example: You’ll never see her Precise Wristwatch referred to as just her watch.

Blackett: The next two sentences to me feel just clearly better, because she’s having this really deep moment of dread, imagining Brutus dead. It’s speaking to her trauma in a way that, in the book, we don’t know about yet.

Guernica: Tell me more about the process of coming up with all the brand names. At what point did you go back and swap them all out?

Blackett: We always had the brand names. But I would guess that there are many more branded objects in the final draft. We needed to decide which objects we wanted to be part of the STÄDA world and then along the way we were like, actually everything should be part of it. Once we made that decision, we had to make a big running list of the objects that were already branded so that as people were moving about their lives and homes we could make sure that if an object appeared, it could be catalogued correctly within the objects we already knew about.

Gleichman: We tried not to orphan any branded objects. If a Polite Hamper appears in one chapter, we’d make sure it appears in another somewhere, so that it feels like a real world. I think that’s true of all the details in the book. And we wanted to come up with adjectives for these objects that were friendly. You don’t want to pick up an Angry Hamper; you want to pick up a Polite Hamper.

Blackett: We also wanted to avoid a product name that felt too redundant or obvious. I don’t think we would have wanted to call it a Bright Candle.

Gleichman: Yeah, a Proud Candle is more interesting than a Bright Candle. We wanted the products to feel really alive and appealing. I think you can tell which of those names we came up with early on. The Comfortable Mattress was a first draft that made it all the way through to final, that looking back I think is too prescriptive.

Guernica: The book has so many twists and turns. I’m curious about how that evolved and how you constructed those things — and whether they were part of the story from the beginning or emerged in revision.

Gleichman: We didn’t know the twists at the beginning of the book. Early on, Ava gets into her car to drive home after this disturbing meeting at work and the car doesn’t start, and Mat gives her a ride home. Originally, it was just that her car broke down and didn’t start — doesn’t that suck about old cars? It wasn’t until later that we came to realize that he was the one who messed up her car.

Blackett: Originally we just needed a way to get Ava and Mat in the same place, and the only thing about it that was more interesting than that was that the car had been her father’s. So there were some emotional stakes, but we didn’t really know that we were laying the groundwork for anything else. Writing the first half of the book, we were in this really generative space, inventing a lot of details, introducing a lot of ideas and characters and media. We had this goal of writing something suspenseful, and when we got to the second half of the book we basically mined the first half for opportunities to do that.

Guernica: Did you ever disagree on anything creatively?

Gleichman: It’s funny that we satirized STÄDA’s so-called “Positivity Mandate,” because that same — though unspoken — mandate worked very well for us; we really never said “no” to one another’s ideas or chapters. If we ever disagreed creatively, we kept that disagreement quiet, at least until we gave the controversial idea a shot. That wasn’t out of politeness, it was out of a commitment to the project we had assigned ourselves: to write a novel together. I do think Laura is an easier writing partner for me than I am for her; I get scissor-happy when revising, and there were a couple times when I cut away something that was actually working well, and Laura would have to tell me to put it back. She was always right.

Blackett: I don’t think I was always right, but that is generous! I think we came to learn how flexible we each are in revision, which made it easier to try things out. I knew that not everything we conceptualized and drafted early on would make it, which actually lowered the stakes for forging ahead. We also rarely brought up a problem without immediately pitching solutions for it. I would say we had a few very minor disagreements at the line level, usually around keeping vs. cutting something, which I remember intensifying as we approached our final draft. The less the novel changed in revision, the less I wanted it to change. But the process of fighting for or against a particular line was actually really instructive, which speaks to the broader experience: Revising and cutting always taught us something new about the story.

Guernica: Did writing this book change your friendship?

Blackett: I feel that we’re much closer friends, having written this book. We were already good friends, but we were writing about love and grief, and I feel like I learned a lot about Eve in the process.

Gleichman: And writing a sex scene together — not easy! It was nice to have this special thing that we were working on together, that existed privately.

Blackett: We started to notice people and things in our lives that we wanted to incorporate, and we would share that with each other. Without the book project, we wouldn’t have had a reason to share a lot of the stories that we did.

Gleichman: We had to trust each other. There were times the book went in a direction I would never have conceived of myself, that was really more Laura’s idea, and just going with it, strapping in and seeing where it goes…I think that inevitably drew us closer. A common response we get from other writers is, I can’t believe you wrote this together; I could never do that. I think if somebody says that, it’s probably true. It’s good to know that about yourself. But I sort of have the opposite feeling: I cannot imagine writing a novel alone. I just can’t imagine writing a whole book without Laura.

Guernica: Is this the kind of book that you thought you’d write? And, or: Is this the book you thought you were writing?

Blackett: After we sent it to a group of really early readers, they said that they had laughed while they were reading it, and I remember feeling really surprised. I didn’t realize that we were writing something funny, I didn’t realize that we were writing a satire. Somebody pointed out recently that it’s not hard to satirize the tech industry or contemporary corporate culture; you just have to describe it as it is. I felt like that was what we were doing.

Gleichman: I think we’re both really able to find the humor in heavier scenarios in our lives. So looking back, it doesn’t surprise me that we’ve written this sort of suspenseful and at times really dark book, but that’s punctured with these bursts of levity. I think it’s a fun book, and I’m not surprised that it’s a fun book. Because I think we’re both really down to have a good time.

To read more interviews from our Back Draft archive, click here.