Miscellaneous Files is a series of virtual studio visits that uses writers’ digital artifacts to understand their practice. Conceived by Mary Wang, each interview provides an intimate look into the artistic process.

The classy thing to do when introducing interviews is, I imagine, to praise and depersonalize, but I’m afraid here I must wax unprofessional. Rivka Galchen has been something of a first sister and mentor to me, both on and off the page, and I know I’m hardly an exception. Rivka is the kind of reader who will judge your work according to whether or not you sound like yourself; the kind of person who will meet you uptown for French fries and cake after you make the abrupt decision to, say, move out of your apartment, out of your life, pack most of what you own into a duffel on the back of your bike — and who will greet you with unshocked patience, glossing over patently unwise choices in logistics and transportation.

This expansiveness of spirit — Rivka’s ability to greet with equanimity the range of what life coughs up, and the various ways in which it coughs us up — is reflected in her acclaimed fiction: Her debut novel Atmospheric Disturbances (2008) and story collection American Innovations (2014) are marked by irreverence, humor, and a touch of obsession. It is further evidenced by her wide-ranging reporting and criticism for The New Yorker and The London Review of Books, as well as by her 2016 memoir on motherhood, Little Labors, in which her daughter appears as “the puma.” A novelist, reporter, essayist, doctor (she earned her MD at Mount Sinai), and professor of multiple genres in the MFA programs at both Columbia University and NYU, Rivka’s essays cover everything from Kafka to children’s books to earthquakes. She’s written her own novel for young readers, Rat Race 79, which is studded with math jokes, and displays a rare quality that I myself, as an adult, am always relieved to find: Finally, here is someone who will not lie to you, not least because of your age. In short, Rivka’s is a mind attentive to the world, appraising what Henry James called the “human scene” from an analyst’s remove — and yet with all the warmth of a relation of care, and the awareness of how connected we all are.

In a moment when it feels like American literature and its authors are often apologizing for themselves and their books — when we struggle to make compelling arguments about why, in this era, we continue to write literary novels at all — Rivka has continued to produce fiction without a sense of shame. With a sense of playfulness, even. Her most recent novel, Everyone Knows Your Mother Is A Witch, strikes that distinctive Galchen balance: Highly responsive to the zeitgeist and all its many menaces, it also achieves that novelistic quality of being self-contained — a world unto itself. Set in seventeenth-century Germany and based on true events, the book revolves around the literal trials and tribulations of Katharina Kepler, mother of the famous astronomer Johannes Kepler, who in 1615 was tried for witchcraft. It’s a story of female testimony and miscarriages of justice and the timeless power of gossip, subverting expectations with emotional misdirection and sly comedy.

For this iteration of the series, we’ve revised the usual protocol for the exchange of files just a bit: I began our interview by sending Rivka a few selections that reminded me of her new book. Rivka then responded with files of her own.

1. “Meanwhile, one child is skateboarding indoors, and the cat is chasing a marble.”

Stevens: This is a picture of a defunct cuckoo clock that used to hang in my childhood bedroom. The aproned woman, now detached, used to sway to and fro on a swing beneath the tree. It’s supposed to be sweet — a clock for a kid? — but, like a lot of woodland kitsch, would probably also be perfectly at home on a David Lynch set.

Everyone Knows Your Mother Is a Witch thrives on exactly this kind of productive tonal dissonance. Leonberg is a small, cozy, wooded town that’s revealed monstrous undertones. Accused of witchcraft by her own neighbors, Katharina is soon facing torture by thumbscrew and death by burning, yet her account is often lighthearted, irreverent. How did you approach comedy, however dark, in this book? What considerations or influences went into calibrating the tone?

Galchen: Detached from her swing, she appears to be doing a Schwarzenegger flex? Maybe that aspect of her posture, latent, patiently waited years to reveal itself. What a clock. We were also cuckoo for cuckoo clocks in my household.

In terms of tone, Katharina’s voice seemed to me too intelligent to not be “light,” at least at times. I didn’t want a pornography of suffering and sadness, mostly because that seems untrue to me. The husband of a dear friend of mine has been dying a long, slow, devastating death from cancer, and when she talks to me about it, there’s a lot of laughter. How else to respond when a hospice nurse pulls her discreetly aside to say he thinks her husband may soon suffer an aortic rupture, and so she should dress him in dark clothes, and put dark sheets on the bed, so that the sight of the blood will be less traumatic for everyone? Meanwhile, one child is skateboarding indoors, and the cat is chasing a marble.

Also, in Katharina’s situation, there’s something inevitably comic in her instinct that truth and reasoning will be consequential, and the way that is juxtaposed against the abundant evidence that they won’t be.

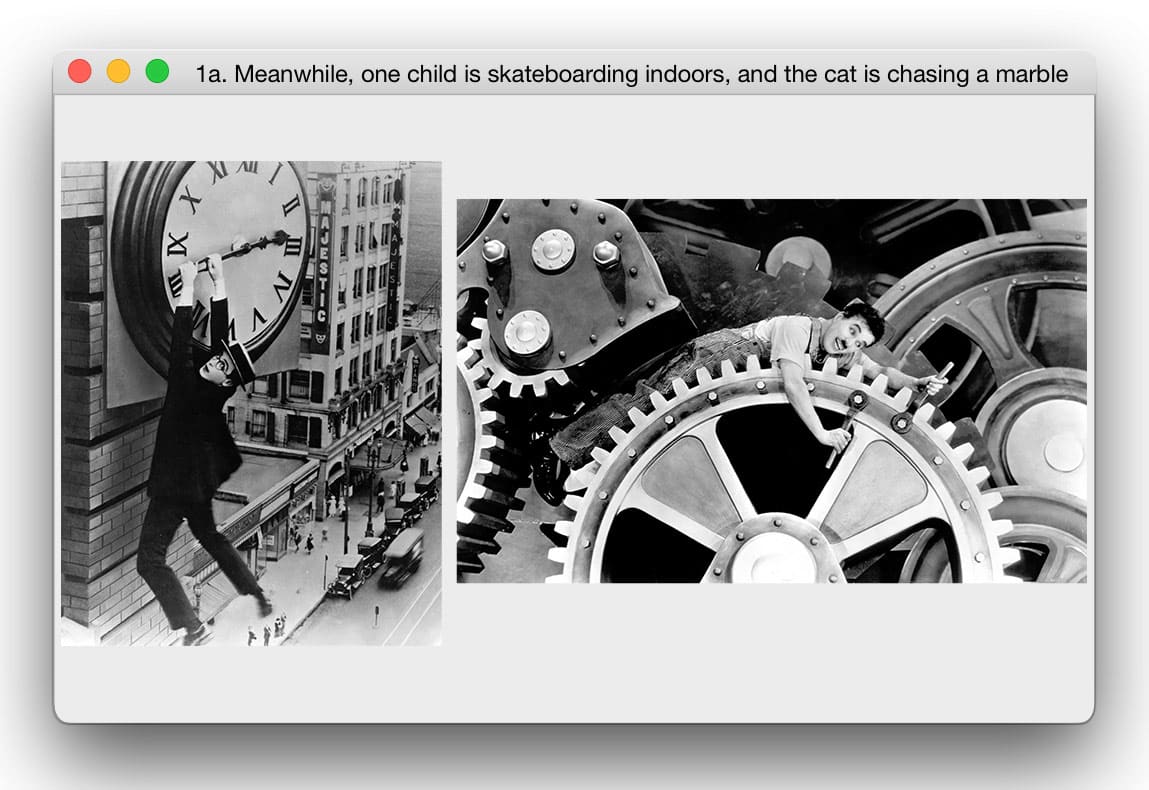

Your clock is reminding me of the famous clock moment here in the silent film comedy classic, Safety Last! And also of this bit from Chaplin in Modern Times. All the physical peril, the vulnerability of the body; it’s absurd, unbearable, violent, goofy. Those old movies, which as a child I remember showing on the TNT channel — they were present in my mind for the writing of this novel.

Left to right: Harold Lloyd, Charlie Chaplin.

2. “Women were asked for visible signs of repentance for crimes they did not commit.”

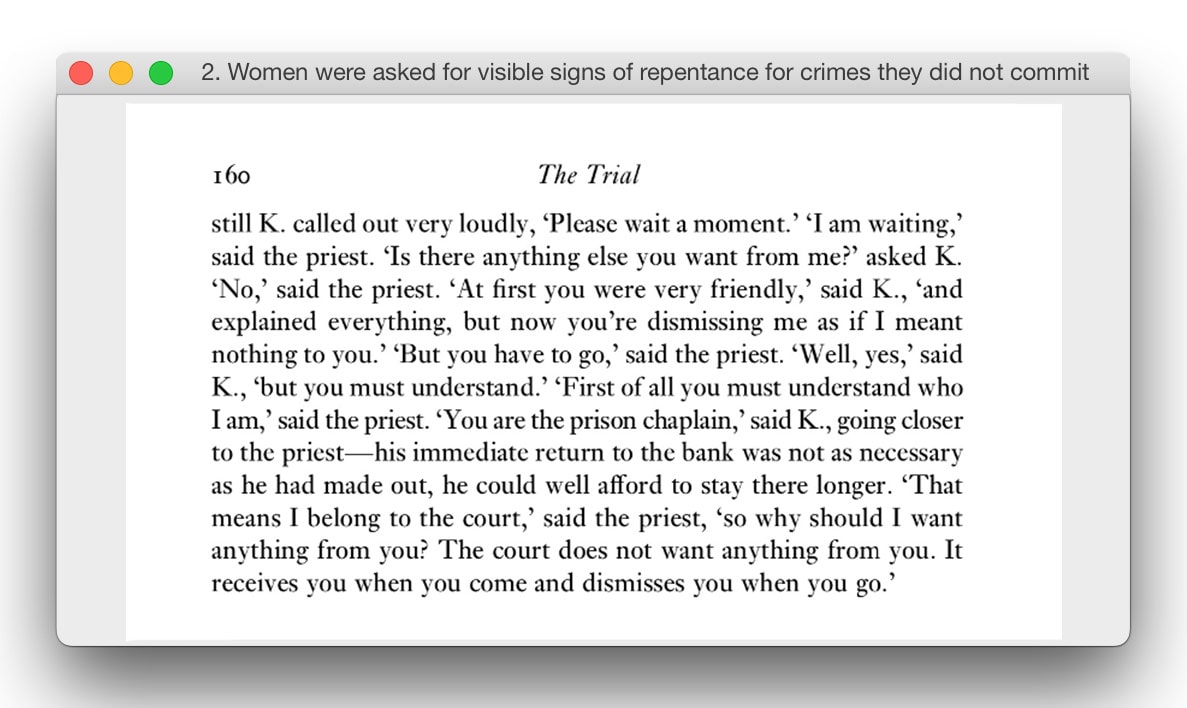

Stevens: There are a number of found documents in the novel — letters to the Duke, court testimonies — that sketch a portrait of a robust seventeenth-century legal system that’s been hoodwinked by its own superstitions, biases, and labyrinthine technicalities. (Among them: Katharina needs a male escort.) I was reminded of the absurd proceedings in Kafka’s The Trial, where officiousness wins out over justice or “truth.” As is the case with Joseph K, the court in Everyone Knows is often deceptively “friendly” to Katharina.

I think you’re quite right that there’s something inherently comic about Katharina’s conviction that reason will prevail, an intuition K shares in The Trial all the way through to that final scene when — well, I won’t ruin it.

But how accurate is your depiction of the legal proceedings of the era, and how did you navigate the fictionalization of court documents? Would we be correct in entertaining the suspicion, as I often did, that the miscarriages of justice outlined in Everyone Knows might rhyme just a tiny bit more than is comfortable with contemporary standards of legal justice?

Galchen: The legal proceedings are pretty accurate in spirit, if “accurate in spirit” isn’t a nonsensical term. Katharina Kepler’s real trial was longer, and had even more turns than I put in the novel. I condensed documents, and also integrated character information into testimonies — but I still strove for emotional and contextual accuracy. I used the historical language strictly for the opening question of the depositions: “Do you understand that any false testimony you give will provoke God’s great anger in your earthly life and will deliver your soul unto Satan upon your death?” And they really did expect women, including Katharina, to cry in front of the court, to show true regret, so as to be spared — which means basically that women were asked for visible signs of repentance for crimes they did not commit, and if they didn’t provide it, they risked facing worse punishment. We know variants of this form of confession extraction are still around.

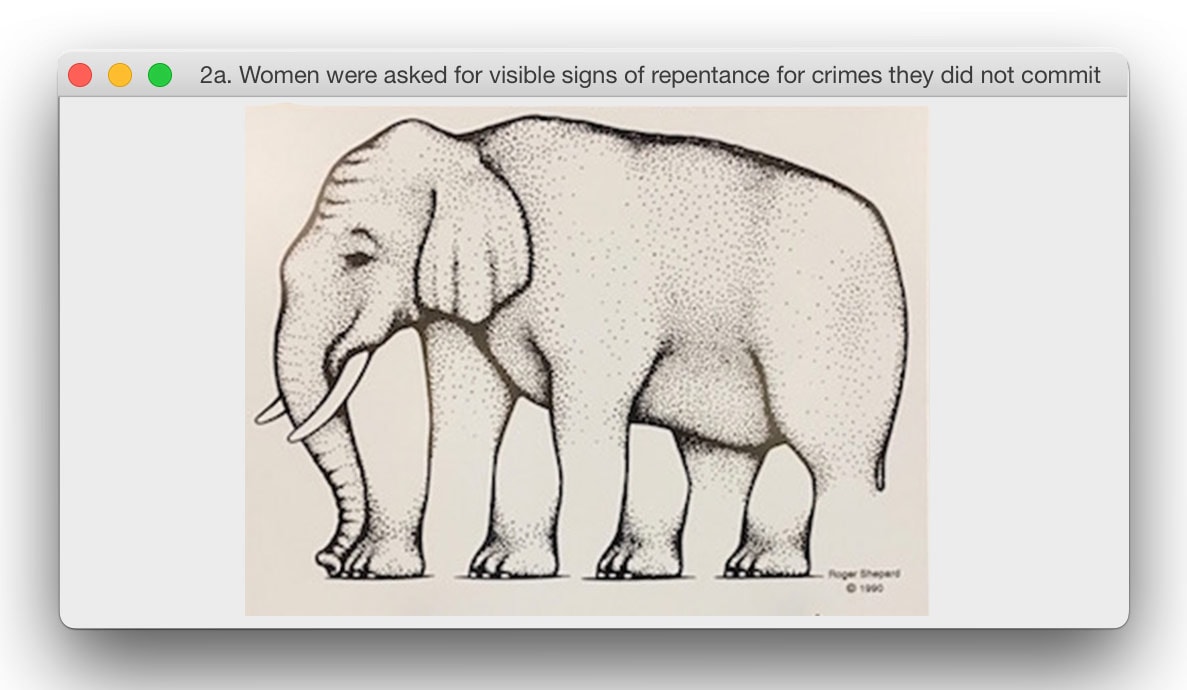

I’m often drawn to stories and formulations that are in some way paradoxical. And the law, written up by people sensitive to the cadence and seductions of logic, but also constrained or ruled by power structures, often ends up generating paradoxes. Same for the ego, I think. The logician Raymond Smullyan has used the term “self-annihilating sentences” for sentences such as: I am a liar. A visual correlate for all these elaborate tangles attempting to be rational might be this famously impossible elephant, the “L’egs-istential Quandary” by the cognitive scientist Robert Shepard.

3. “I was fleeing from the news more than responding to it.”

Stevens: I probably don’t need to attribute this tweet, which I’m sorry to dredge up in the pages of Guernica. The news cycle must have dispatched an awful lot of radio interference as you were drafting Everyone Knows, a book about an actual witch hunt, manipulation of the courts, female testimony, and distrust of science. It even ends with a plague, specifically, the second wave of the Black Death, which swept through Europe in the 1660s. This is all to say that, like all good historical fiction, Everyone Knows carries the shimmer of an eerie, evergreen kind of relevance.

But how did you deal with the frenzy of the news cycle and its echoes with the novel during the drafting process? Did you welcome these echoes, or did it ever feel important (if impossible) to keep the headlines at arm’s length from the work-in-progress?

Galchen: I was fleeing from the news more than responding to it. But of course what we run away from often determines where and to what we run. I didn’t consciously connect my novel to the present tense, but that is in part because when I write, I don’t think in terms of themes or meaning. I instead think in terms of altering the velocity of the prose, of altering the tone, of obeying the call of repetitions with variations. That way of proceeding is what feels emotionally true to me, and also serves as a way of staying clear of the op-ed parts of my brain.

4. “I like to think of Death not as a murderer, but as someone with an unpleasant job.”

Stevens: This is a still from the chess match with Death at the heart of Bergman’s The Seventh Seal, whose tone — black comedy mixed with humanity and gentleness in the face of imminent doom — also reminds me of Everyone Knows. (The film also features a minor character who is accused of being a witch.) Katharina may not be a witch, but there’s something otherworldly about her — throughout, she retains the spiritual upper hand. It somehow strikes me that, were we to hold a casting call for The Seventh Seal, she wouldn’t not be at home in the role of Death, despite her position as a hunted woman in the book? Please refute.

Galchen: And they’re playing a game! I love it. Before I refute, I would assent. There she was, one of the oldest people in town, consistently not dead from childbirth, from disease, from heartache — what better way to bring death to every table than by consistently not dying, than by persisting against the odds?

I like to think of Death not as a murderer, but as someone with an unpleasant job, who is unwelcome wherever he or she goes. A debt collector? One of my favorite novels with death as a character is the darkly comic novel, Unclay by T.F. Powys.

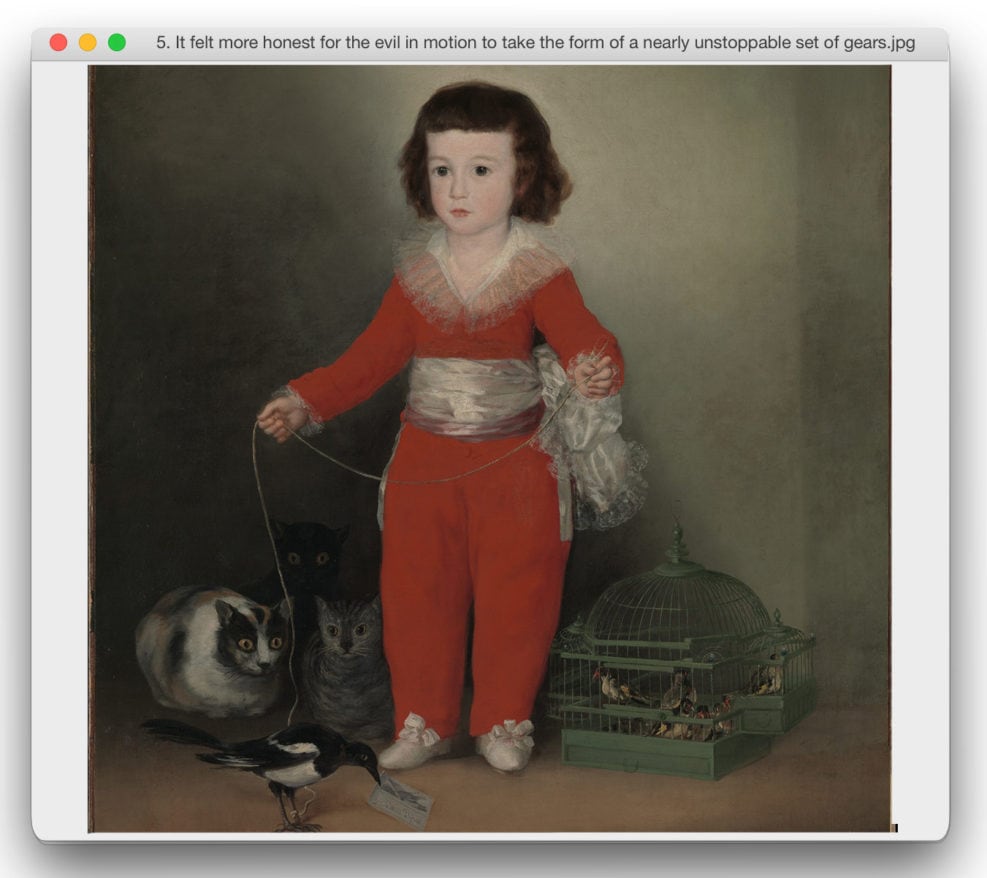

But if I were to refute, I would say: I don’t think Katharina sees herself as pitiable, or in her end days, or even as old in some ways. She connects best to children and to animals, and she is most herself in their realms. Maybe she’s the death that precedes life more than the one that comes to end life. As an image, I think of this as the eerie prescience in Goya’s Red Boy, a portrait of a very pale young boy, with three cats, a magpie, and a cage of finches.

5. “It felt more honest for the evil in motion to take the form of a nearly unstoppable set of gears.”

Stevens: Goya’s Red Boy here also captures, for me, Katharina’s regal, eccentric calm. Also that sense that the natural world is on her side!

We were talking offline (or online, but off the record?) about joking into the void, which reminds me of a sentiment you brought up earlier: How else to respond? I’m very moved by the thoughtfulness of the hospice nurse from your friend’s anecdote. It rhymes with a kind of matter-of-fact attention to detail that I think Katharina shares, and which those around her (including her son, Kepler) might not always immediately appreciate: She sometimes loses the forest (her impending sentence) for the trees (she’d like to go home and take care of her cow).

For all the knocks on realism floating about the Internet (enter resident straw man), the way you relayed that anecdote also seems an argument for it. Or for at least one of its techniques. I’m thinking of that idea of creating a sense of simultaneity of continuous action in a scene, of manipulating time and details to create a sense of overlap: a child is skateboarding down the hall; the cat is chasing a marble; meanwhile, the nurse is outfitting a patient for an aortic rupture. There’s a resonance achieved simply through juxtaposition.

Would you like to comment on…Realism? In relation to Everyone Knows or otherwise? Evasive answers accepted.

Galchen: I think realism is a wonderful genre, one of my favorites. Realism doesn’t mean a webcam. It involves so much sleight of hand, and trompe l’oeil. Just like memory does. For this novel, I felt like I was, even more than usual, leaning on two “tricks” that I associate very strongly with Realism, or I guess I should say Realism as it exists in my mind. One is the charismatic detail — the way a “random” detail can feel like those bits of paper that if you add water to them, grow into a flower. I felt I needed that sort of detail more than in other work, because of the distance in time, in situation. And the second connects to what you were saying about the manipulation of time. The habit of a story to eddy out from what might seem its more proper trajectory — away from trial, trial, trial and into the other whorls of emotion. I found myself keeping Charles Portis’s True Grit in mind while I was writing. The central story of True Grit is a girl seeking out the man who killed her father. But the heart of the story is unexpectedly in other loves, other needs, other noticings.

Stevens: I like that very much. I’m also really attached to this idea of books switching lanes and states — moving beyond subplots into subroutines in the available emotional registers.

Comedy also often operates on juxtaposition of the disparate. For example, in the excellent still from Modern Times you’ve shared, Chaplin’s smiling away while being fed through Rube Goldberg gears and manipulating screws mechanically unrelated to the primary cog of destruction — but very related to Henri Bergson’s observation in Theory of Laughter that laughter arises from the mechanized routines of (modern) times.

The indifference of the mechanized legal machine at the center of Everyone Knows seems to provide that sense of comedy, but also tragedy. Is tragedy mechanized, too? Do I sound like the annoying end of a Socratic dialogue?

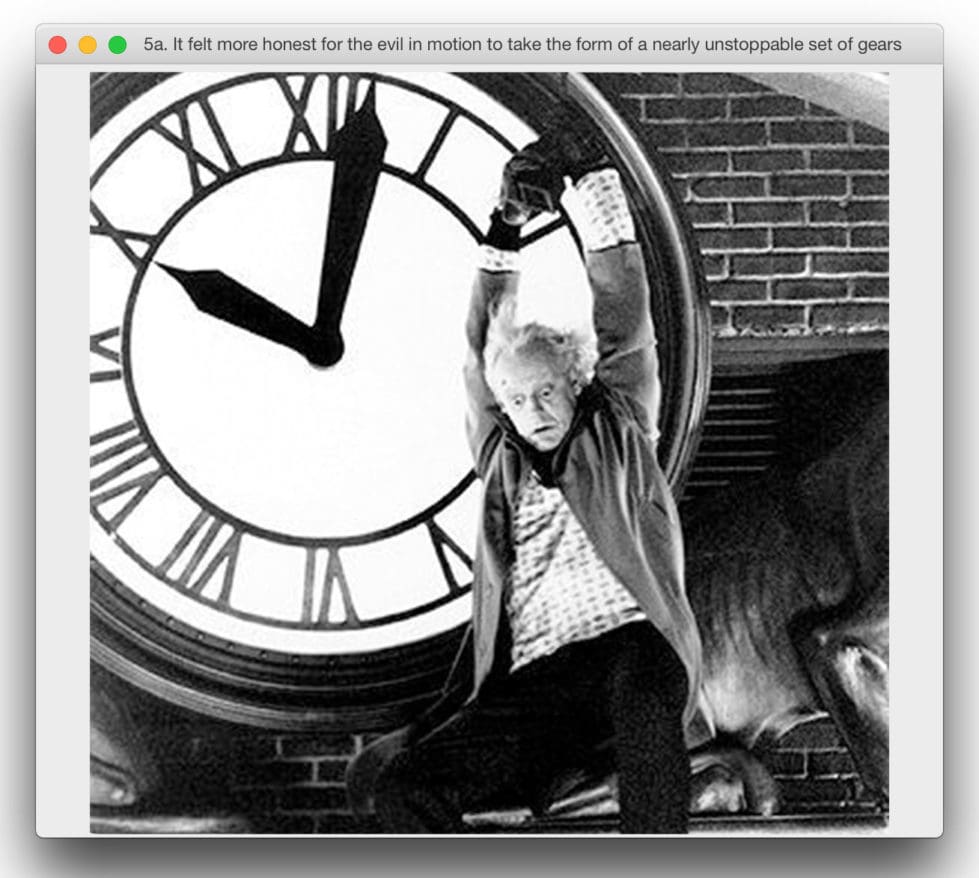

Galchen: I love this train of thought. You’ve made the word JUGGERNAUT appear in my mind, in all caps, and with little mechanized feet on each letter. I wasn’t thinking of it consciously while writing, but I did notice my aversion to giving too much attention to “bad actors”…it felt more honest for the evil in motion to take the form of a nearly unstoppable set of gears, even if some of the gears were ever-present human qualities like envy, greed, ego, and stupidity. But by the end of the novel, I felt that the other tragedy at play, alongside persecution, was the inexorable forward movement of time, as manifest in disease, in cycles of violence, in death. Maybe a remedy for this mood would be the clock scene in Back to the Future.

Stevens: What Back to the Future is to your generation may be what Zoolander is to mine, the latter being better positioned for arguments about the selfie than arguments about novelistic time.

The “L’egs-istential Quandary,” on the other hand, seems to stop time, maybe also remedially, by trapping us in a loop. Regarding that idea of paradox: Should all novels be a touch self-annihilating, like the elephant in the drawing, or like that other famously self-annihilating sentence you’ve mentioned, “I am a liar”? And is that self-annihilation one way in which novels depart from life? There’s something captivatingly self-contained to Everyone Knows, as if the novel would proceed, as is, in the absence of any reader or audience — it exists in its own time loop. Outside of a novel, however, I’m still millennial enough to hope that our understanding of human experience becomes less self-contained, and that political action won’t always lead to existential dead-ends.

Galchen: Yes. Maybe a contagion model rather than an infinite loop or a negative feedback model. One reason I fled the present tense is that I feel so hopeless about understanding why the momentum of the present feels so regressive, why the “light” that I see out there feels evanescent. But I promise, on another day, I’m the optimist, and my metaphors come from places other than disease!