I am trapped in Australia. The borders are shut, which has worked well for keeping COVID-19 out, but it has also kept me in. Over the last fifteen months in sunny Perth, where I live, there have only been two cases of COVID-19 in the community. We have not worn masks, the hospitals have not been deluged, our schools have stayed open. We are in a gilded cage. A friend calls it Sun-tanamo. We both laugh when he says this, but we are not happy.

A year and a half into the pandemic, I am nostalgic for the geography of my familiar. I long for Johannesburg, the city of my heart. When I left South Africa, I expected to go back frequently. There was a daily direct flight, and my frequent visits to South Africa made living here bearable.

But I have not been home since 2019, and my children are beginning to forget how beloved they are across the ocean. I miss hearing women shout greetings across a busy street. I want to see plump brown girls in short dresses laughing in the winter sun as they walk alongside skinny boys in grey trousers and wayward ties.

In my neighborhood here, there are only pale-faced children holding hands with their thin mothers. Australia is so orderly, so quiet. No one calls out above the roar of traffic. There are no kiosks by the side of the road, no vendors selling misshapen vegetables on the pavement.

Australia does not know what to do with chaos.

In early May, as I am trying to power through the ache of homesickness, I begin to see images of India in distress. The calamity of it is so evident; the messiness of death and dying seeps through my television screen. There are many Australians in India, many of them dual citizens who are visiting relatives. Instead of being offered expedited and safe passage home, they are told that they cannot return. The Australian government — xenophobic even in its most generous moments — bars its own citizens from entry. Australians of Indian descent are being reminded of the precarity of their belonging. This is unprecedented but unsurprising.

My children, who are now approaching adolescence, are frequently reminded that they, too, do not belong here. Their accents are as Aussie as they come, and yet their brown skin undoes their belonging, and they are treated as permanent strangers. On a regular basis they are asked, “Where are you from?” This question nudges them towards hyphenation; they fully understand this way of telling them that their accents, their mastery of swimming, their love of Tim Tams, their comfort at the beach — all of these are not enough to make them from here.

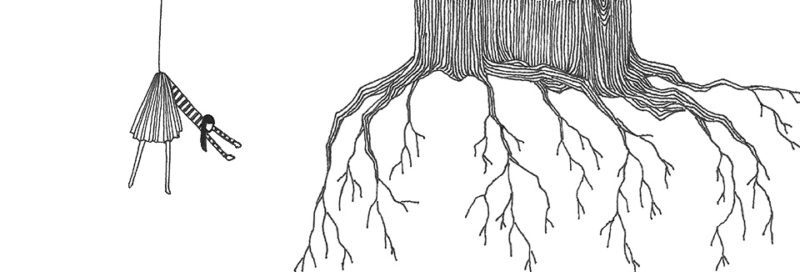

It is hard to accept that they will grow up in a place that is ambivalent about its claim on them. It is harder still for me to accept what all of this means for me. I have lost the sense of self-determination I once had: the ability to escape, to choose where I might be and, yes, who I might be, in Nairobi or Mexico.

Here, I am a mother, a worker, a woman in sensible shoes riding the train to work. In Johannesburg I would never wear sensible shoes. Here I am bound up in mothering, tied up in working; at home I am a different, less-constrained self. There are places in the city I can go to disappear, and places I find myself in order to be seen. My children will not know this duality, and I miss that for them. This pandemic has shown us we can call only one place home, and it has chosen Australia for us.

By the middle of the month I am full of angst, bloated with the sense that we are stuck and will be for a long time to come. There is no escape from the feeling, just as there is no running away from this place. We are safe and sound and lonely, wedged between the Indian Ocean and the wide-open desert.

I want to stay at home and wallow in my melancholy, but I can’t. A dear friend is leaving for Sydney, and I want to see her before she goes. We sit in an Uyghur restaurant called Silk Road, eating cinnamon-spiced chicken with fat noodles. It is a Monday night, but the place is packed and everyone here is from somewhere else and so I feel oddly at home.

I ask her about Eid, how was it? It was heavy she tells me. Palestine. I tell her I know. I have been struggling to contain my sadness too. I am full of a strange new grief I cannot describe. Palestine is under attack and my uncle, who has been a father to me, is sick and may soon die. Even as I tell her this news from home, I rage against the inadequacy of English. What kind of word is “uncle?” What can it say about who he is to me, to us all?

Somehow, these two sadnesses, my private sadness and this public sadness, have become entangled. I can’t figure out the connection. Why does watching the news makes me think of him, and why does thinking of him make me worry for Palestine? I am too tired to try.

My sadness gathers force. At the beginning of the pandemic my homesickness was a pebble, a small stone I carried with me throughout the day. Now, fifteen months later with no end in sight, as Australia’s borders tighten and its fear of others makes the world even smaller, my sadness grows.

Israel’s latest war against the Palestinians, who have already endured so much, has dislodged something in me. A video of a ten-year old girl speaking to a journalist has been doing the rounds on social media. The child is surrounded by rubble and perhaps she is in shock, or perhaps she is simply fluent in the language of loss, more eloquent in her outrage and befuddlement than most people ever have to be. Her name is Nadine, and I play and replay and replay the clip of her saying, “I don’t know what to do, I’m just a kid. I can’t even deal with this anymore. I just want to be a doctor or anything to help my people, but I can’t. I’m just a kid.”

I am struck by how her dreams are bound up in the needs of her people. I imagine that to be a Palestinian child is to be Palestinian first. I cannot know, of course, but it seems to me that before you are a child, you are a Palestinian, subject to all the discrimination and violations rained on your people by Israeli apartheid.

I understand her. I was ten when Soweto exploded in 1984 and we were so far away — in exile — but I, too, would have done anything for my people. I am devastated for us. Pained by her reality and sad for the little girl I once was. I sit in front of my computer at work witnessing the shock of a freshly wounded child. Her tears trigger my own long-ago grief.

My mother married a freedom fighter and gave birth to my sisters and me — three baby revolutionaries — and still she was surprised that we carried the weight of the world on our shoulders. We cared too much. Our eyes were always leaky. She worried that the brutality of the world would break us. It didn’t. We have always navigated cruelty by doubling down on love. Grief is another word, of course, for love. We don’t mourn those we never cared for.

In Greek mythology, when the Titans lost their battle with the Olympians, Zeus condemned Atlas to hold up the sky. It was a perverse penalty: Zeus used Atlas’ greatest asset to hurt him in perpetuity. To carry the weight of the world on your shoulders is to be sentenced to hold that burden, not just for a minute or a day, but for eternity.

The day after our dinner at Silk Road, my uncle dies, and I sit in bed as though I am sick, with a blanket covering my legs. The children bring me tea in bed like they do on Mother’s Day, and I cry at the sweetness of it, and also, I cry because nobody knocks on my front door to offer condolences, and nobody will.

At home, in South Africa, death brings the neighbors and the house overflows and at dusk we sing until we cry, or we cry until we sing. We pray, even those of us who are godless, and we call out to our ancestors. Here, in Australia, someone could die on our road, and we might never know it. How can mourning be a private affair when grief does not know how to stay inside?

I stay up every night for the vigil, which takes place at 6 p.m. Johannesburg time, midnight in Perth. I keep my camera off and weep freely on Zoom. The house is asleep; each new day brings school for the kids, and work for my partner, and so no one can keep me company. There is no one to wail with me.

Someone sets up a WhatsApp group called Uncle’s Gallery, and people begin to post photos of our father-uncle there. I look at them religiously. Collectively they are an atlas, carried across many homes in the many countries where we lived as exiles. In each photo, he is both living and waiting.

His death reminds me of our own exiled waiting. I remember that for decades, our lives were a long-held breath until finally we made it home, at first stumbling into the country after Mandela walked free and then finally running towards our own freedom, towards elections and the collapse of apartheid.

I go to a protest in support of Palestine and there is a woman holding up a massive poster that lists the names of the children who have been killed in the week since the bombs began to fall. I can’t imagine how long it took her to write each name.

I stand in front of her for a long time, reading each of the names she has lovingly spelled out. Today, anyone who has been watching the news can tell you who George Floyd was, and Orlando Castille and Tamir Rice and Trayvon Martin and Sandra Bland and Breonna Taylor. We know about the precious Black lives lost in America’s war against Black people because American Black people have insisted on it. Protesters have chanted, “Say their names,” and we have. And even as the list grows, as new names of young people killed by police officers multiplies, we know that we have a duty of solidarity. Around the world we speak their names.

Nobody talks about how Palestinians die in webs, in family groups. One death is a tragedy. What is the word you use to describe the killing of many people who are connected by blood and love? The dead cannot bury the dead. Who buries everyone when no one is left?

Dr. Ayman Abu al-Ouf was killed with twelve members of his family in Gaza. He was killed at the same time as his father and mother, his wife Reem, and their seventeen-year old son Tawfik and their twelve-year old daughter Tala.

There is a picture of Tala in an article about them. She is wearing heart-shaped sunglasses and underneath her mask you can see a smile, which reminds me of my daughter’s smile. They are the same age. I read that her brother Omar, who is fifteen, is the only member of the family who survived. The article says, “at the time of writing,” Omar is being treated for injuries and no one has told him yet that his parents are dead, and that his grandparents and siblings are dead too.

Even as I tell this story I know that the names Ayman and Tala and Tawfik are not neutral, that they are not simply names. They are Arab-sounding, and so to ask for these names to be called out in tenderness, to be invoked in empathy, is to perhaps risk the opposite. In this country there is so much hatred directed at people who look like ten-year old Nadine. I am not convinced that Australians will twist their tongues to speak the names of strangers whom they have learned to vilify, but the work of insisting must be done.

The call to say their names is, of course, only the beginning of the work ahead. I understand now that my grief is an offering, that their names are an opening prayer, a step in the long road to Palestinian freedom.

In my favorite photo of my father-uncle, he is standing underneath a sign that reads “ora et labora,” pray and work. He is smiling and serious, as he always was. I must have heard him say this a thousand times in a thousand ways as we criss-crossed the globe in search of freedom.

I am saying through my grief for my uncle who worked so hard to free South Africa, that the work of sanctions and boycotts and remembering is interconnected, but ultimately we do not want to love only the dead. To grieve is not simply sentimental; grief gives impetus to organizing, and this is how we live. I want Nadine to grow up and live in a free Palestine, and I want to dance in the streets with her when that time soon comes.