Ten

This is the beginning of my body. My mother tells me it’s time to go on a diet, and I believe her. I begin to act accordingly. Her words are borne from love, but they are powerful, they take root, they last longer than the pounds do, than my childhood does, but I don’t blame her. My mother is a dietitian, which means she has developed control over her weight, and now she wants to teach me self-control so that I can live a healthy life in a healthy body. She also wants to protect me from a fat body, and the hatred that surrounds fat bodies. Just for a little while she says, “Just a few pounds heavier than I should be.” She says, “Don’t let the boys peek down your shirt, either.” She says, “Be careful when you lean over,” and I am even though I don’t understand why they would want to. Sex is still shrouded in secretive Christian magic. When my older sister gets her first period I’m afraid she will be impregnated from lying in bed with my parents the way we all do on lazy Sundays mornings, under the thick cream comforter, piling on top of each other. My mother still dances in front of the television shaking a blanket every time the characters start kissing, her knees lifting, torso jerking, He has the whole world in his hands the whole world in his hands.

Eleven

I learn what sex is on the school bus from a hooded eighth grader who makes demonstrations with his fingers. The boys on the bus cluster around him like he is their king. A small but powerful pack, they spend the thirty-minute drive shouting “Boobs!” and doodling hairy penises on the frosted back windows. I am still a painfully quiet turtle-like creature. Under my shell I convince myself I am sexless and therefore invisible—no breasts, no vagina, nothing that can be exposed to the light.

Twelve

Nothing I pray wards the breasts off. When they arrive, I press them down—I press them down. The hips come next and all at once I have curves for miles. My female classmates are reedy, prepubescent tweens—elegant, no jiggle, like the models that drape themselves over one another in mall windows. Chiseled stomachs, arms like rods, legs without thighs, selling us bras and jeans and makeup products.

There are twelve mirrors in our house. I often pass from one room to another, watching how I change in the light. My father grew up in this house; he says the neighborhood has changed over the years and that’s why he installed the fence and the alarm system and the security cameras, but I have never felt vulnerable in this house. My room is like a fortress, or a womb; it keeps me safe, and small. I’m not allowed to walk anywhere alone.

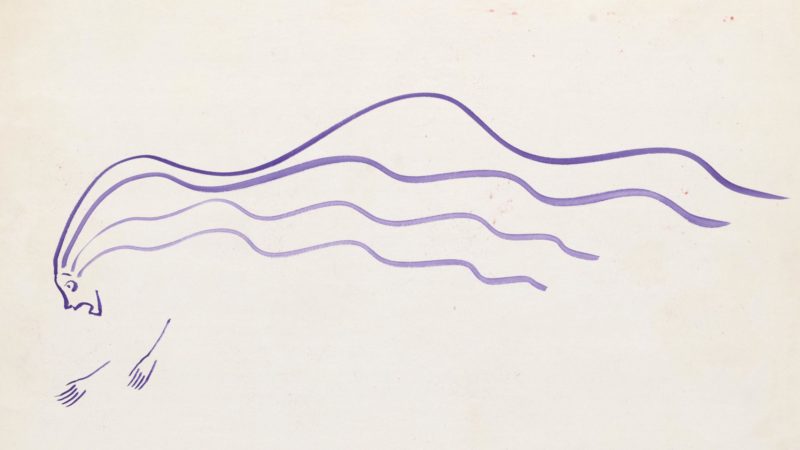

We live an hour from the beach, which my mother loves for all of the obvious reasons: the sun, the shells, the mysterious water spread out endlessly before her, but I hate the baking heat on my shirt and shorts, and the parade of girls in string bikinis. When I’m at home, I lift up the tail of my shirt to look at my pale ocean of skin in the mirror at the bottom of the stairs. I do this in the early mornings and after dinner, every time I switch clothes, watching the surface of my body change with the moon, the ribs poking through and then sinking below. I imagine I am an artist shaping my body, gathering flesh like clay in my hands and sawing off the excess. I swing between emotional tides of determination and then disappointment, back and forth. I eat myself to the point where I have to lie down and shut off the lights. Then I restrict my daily caloric intake to two pieces of chicken and a banana after running for thirty minutes. This is the power of creation and recreation. A never-ending cycle, an infinite reality, I can always become better.

The boys cleverly insert the word “titty” into my last name.

In his essay Sexual Objectification, Timo Jütten explains how sexual objectification teaches men and women to assume roles as superiors and subordinates, roles that disadvantage women and leave them vulnerable to gender-specific harms, such as sexual assault and rape. While I knew this already, it is a small relief to read it in print. Most women instinctively know that their bodies are a hair’s breadth away from violence. The artist Marina Abramović demonstrated this by laying seventy-two objects on a table—a tube of lipstick, a feather, a knife, and a gun—and invited gallery viewers to do whatever they wanted to her for six hours. At first the people were shy, presenting her with the flower, kissing her, draping her in cloth; then as the hours ticked off, one man snipped off her clothes with the scissors so that she was bare, and another sliced her with the knife. Someone else picked up the gun from the table, wrapped her hand around it, and pointed it at her neck. At the end she stood up to leave, bare, and bleeding, and the audience fled.

Thirteen

I am told that I am not quite fat and not quite popular. Most days I straighten my hair into a thick, black curtain because Steven once said it looks better that way. While I am neither anorexic nor bulimic, I am repulsed by my body and its shape, its basic anatomy, all the flaps, the holes, the hair. A woman is supposed to be straight, with shiny, hairless skin. I crave that kind of power.

My mother begins teaching me her language:

Lean protein greens no starches no sweets one serving of carbs the plate should be three-fourths vegetables meat the size of a deck of playing cards the more color on the plate the better diet soda only Splenda not sugar forget chips and forget ice cream and forget the friends who eat chips and ice cream and don’t gain a pound at a restaurant order sautéed sauce on the side when a craving occurs chew a piece of gum and think about something else if the craving gets bad have a bell pepper instead halved and sprinkled with salt if you’re hungry you ask amIreallyhungry?

When motivated I can lose a pound in three and a half days.

At some point, professionals start to gather data, and the “thin ideal” emerges. While this is not a new concept, media intensifies its effects. We know that the standards of aesthetic ideals change between eras and culture and country, encompassing whatever seems most unattainable in the given moment, which means we shame the majority and idolize the outliers. Across the world, data show that girls as young as six hate their bodies. Across the world, a common female language develops: you are not what you should be.

That is what I tell myself over and over again until I lose fifteen pounds on my chicken fruit diet and my treadmill regime and I flounce around the house in white tank tops, collecting compliments from my family. I flit from mirror to mirror and room to room until a cold dread settles into my body. That sick feeling you get when you’ve lost something important. Over the next two months I lie in bed with chips and ice cream, and my breasts sprout breasts and those breasts sprout breasts and all they say is: shame shame shame.

Jütten explains the trend in Western societies: women embrace their objectification in order to experience it as empowerment.

We post our bodies online to be viewed and appraised by others, often men, and we contribute to shameful comparison with other women. This is the power afforded to women: the power of beauty, and sexuality, and desirability. We act as if, could we gain control over our image, we could gain control over our bodies and boundaries—as if we can then dictate what happens to them, with whom we share them, on what terms we expose them.

We cannot, of course. We are just objectifying ourselves, and calling it liberation.

Fifteen

Maggie is telling me about the guy who grabbed her vagina at the movie theater on their first date, like a little boy groping his own genitals.

I try not to dwell on this the same way I try not to dwell on the way the characters in my books have started sleeping with each other as if it is inevitable. When the boys in math class talk about fingering and blow jobs I roll my eyes. I am not a sexual being. I have a purity ring. When two men in a truck pull up at the red light beside our car, when they roll down their window and bark at me, flapping their tongues, I pretend not to care. I look away and the light turns green.

Seventeen

I tell myself it’s something about men in cars, the muscle of an engine, the godlike speed, the steel frame cage. So when I am in a car with a boy, I mean in a parked car with a boy, and he begins rolling my seat backwards in a practiced way, I am careful. He is focused, really giving it his best, but his warm breath is sour and oppressive, and I don’t know how to properly work my lips. “We should have sex,” he says. He laughs like he doesn’t care either way, and then rocks the car, demonstrating his abilities.

He doesn’t know that he will have to propose if he ever wants to see me naked. He doesn’t know that I worry that he wouldn’t like what he would see because these days the numbers on my scale are rising steadily like the summer heat.

While my friends post picture after picture in bikinis on Instagram, my doctor gives me a slip at my annual checkup that says something like, your BMI is higher than recommended for your height and age.

When I leave that appointment, I drive with my little sister to McDonald’s and we hunker down in the family Volvo with our hot cakes and French fries and honey mustard and a ten-pack of chicken nuggets, swallowing in between bouts of tears. It’s the week before I leave for college and this is our closing celebration, we call it Fat Girls Take McDonald’s.

Self-objectification is a term we hear less about. We almost don’t hear it at all. We have grown accustomed to speaking about ourselves with shame and judgment, in the language of objects. I want to go back to the Garden of Eden, back when the body was still just a body, unclothed, and a part of creation, as shameless as a lion’s mane or a deer hide. But then Eve picks the fruit and hands it to her husband. And while some ancient philosophers and theologians curse Eve, the evil temptress, and insist all women should be subdued by men who will lead us and teach us, I keep thinking about the way she picks the fruit. The way she hands it to her husband, the way he takes it like a child, the way he doesn’t say no. He doesn’t begin to lecture her on the sanctity of divine commandments; he eats it without a thought, and suddenly they know that they are naked, and the shame begins to whisper, hide.

Eighteen

I’m in control again. Every single day I shimmy up a treadmill inclined to simulate an indoor mountain. I shake the ground beneath me. Fifty minutes at an uphill climb set at 4.3 mph is four hundred calories subtracted from my eight-hundred-calorie allotment. I discover Drake. His verses are cruel and satisfying. I sing as I artificially climb:

Get a plastic bag

Go ahead and pick up all the cash

Go ahead and pick up all the cash

You danced all night, girl, you deserve it

I begin to recognize the faces of the gym. I know how long the men have been there, peeking at themselves in the mirrored walls because I’ve been doing the same thing. Night after night I consume my dry salad with my dry chicken until one of my new friends tells me that I’m improving. I am an artist at work, I keep climbing, keep singing.

I got so many bad bitches that I barely want ’em

I’m barely paying attention, baby I need substance

I know you spend some time putting on your makeup and your outfit…

I lovingly break it to my older sister that the reality is most men are attracted to thin women, that’s just the way it is. The context is that she can’t fit into a dress that she’s wearing to a wedding, and she wants a boyfriend. She says something sad like, “I just think with the right guy it won’t matter.” I want to help her. Her whole life she has never really said anything negative about the way she looks, and we are on our way to get donuts. She begins to cry and I feel bad, but I don’t realize what I’ve done until she begins to shed the weight and we celebrate each pound as a family. She loses ten pounds, then thirty, and now she lifts up her shirt to show me her stomach so I can see the difference. Now she says things like “I look so fat” and “I just want to look like you.”

In 1968 Jane Elliot led her third-grade class of students in an experiment to teach them the power of language, specifically the power of language that promotes hierarchical systems of oppression. She tells her class that melanin causes eye, hair, and skin color, which in turn determines intelligence. She concludes by saying that since brown-eyed students have more melanin, they are more intelligent and all-around better than blue-eyed students. She says, “Blue-eyed people sit around and do nothing. You give them something nice and they just wreck it.” Then Elliot studies the divisions that unfold when the children begin acting their prescribed roles. Brown-eyed students come out of their shell, acting with confidence and berating the blue-eyed students. The brown-eyeds call the blue-eyeds “Blueys;” they say they’re dirty. Elliot notices how one intelligent girl with blue eyes begins to make mistake after mistake in her classwork. Her body language changes; she begins slumping. At recess, when three brown-eyed girls tell her that “they are better than she is,” the blue-eyed girl apologizes.

Twenty-one

I’m at the OBGYN office because I need birth control and you can’t get that unless you suffer through a pap smear. First off, I am wearing a toilet paper dress that opens in the front. The doctor comes in with a large-boned nurse that reminds me of a bodyguard or a posse member, and asks me to lie down and open up my toilet paper dress. She begins to search my chest for tumors and I lie there, staring at the ceiling. After all these years, she is the first person to touch my breasts. But what’s worse is that I know what is coming, and I want to say something pathetic like, “I’ve never had anything inside me,” but it doesn’t feel like the right time and I figured she would understand this from the way I am sweating. I close my eyes, and I feel a sharp pain near my belly button.

They bring me back with smelling salts. I wake up to my mother patting my hair. When I say, “I’m getting married in a month,” they promise me sex will be fine, just have a drink. They didn’t know that I would walk around that whole day feeling like some kind of survivor.

Twenty-two

In my new home there are no mirrors on the walls besides one placed high above the bookshelf, over the fireplace where there is no fireplace anymore, just a ledge. My husband leaves me alone in this house three nights a week to work at a bar because he believes he needs to make side cash, because it’s hard to swallow nine-an-hour with a college degree and a wife who is making more sitting every day with a stranger’s baby. I don’t want him to leave. When he leaves, time suspends, and ours is the only house on this street where men drive recklessly, their voices spilling from their cars, and people wander through with their shopping carts full of old shoes, making high-pitched cries that pierce through the thin walls and leave me wide-eyed and frozen in place. On these nights especially the door seems like a slim, wooden plank, easy to snap. The lock seems cheap and fragile, and what then is this house? What is a house that’s incapable of defending the barrier between inside and outside?

What then is this body?

They say that after you’re married the shame is supposed to end. But when I can’t have sex, when I seize up in panic, when I don’t want my husband to look at my body too closely, because my body is still disgusting and foreign to me even now, the shame begins again, and this time it is different. This time I am a wife, and a wife is supposed to please her husband. This time I am not pure, I am just dysfunctional, and now the story is our marriage is not consummated until it is consummated, because intimacy is nothing when you have not been penetrated, because at the end of the day we are all just kids mimicking with our fingers how it should be done, dictating what is right and what is shameful, and who is ugly and what is pure—there is so much fear coiled up inside me—and this time the shame says: you have no right to be broken.

Vaginismus is a disorder defined as the involuntary tightening of the muscles surrounding the vagina, especially while attempting intercourse. It often stems from fear or shame associated with penetration. It cannot be willed away. It is both physical and psychological, most often affecting women from religious backgrounds all over the world, though they rarely talk about it. Either we learn to live with the shame, or we quietly recover in physical therapy, learning how to rewire our brains and our bodies, learning how to relax when someone touches us, when someone looks at us.

Twenty-three

The child I take care of lives in a house full of windows and long, wooden hallways littered with plastic toys. I never have to lock the door. We topple through the rooms pushing balls and spilling into the yard stretched out under the shade of magnolia trees. All day the baby gurgles and glubs in humanlike imitation of “ball” and “da-da.” I am teaching him how to say “bird” and “dog” and “bub-bub.” He is learning the delicate rhythms of his world. He knows that the curvy yellow “nanna” is sweet and appears only in the kitchen. He knows about the zzziring coffee grinder, how you turn it on and then watch the beans trickle into the burrs, how you then go to the refrigerator for the milk and how the espresso machine spills steaming espresso into a miniature white cup. He directs his parents around the kitchen, to the sink, to the grinder, now you turn it on, he points what to do next. It’s strange how this is the world we are creating for him, one with an open door, one in which a machine spits out brown liquid every morning stable as the sun appearing in the sky. It’s strange how the words we teach him become the only reality he knows. I could assign any syllables to any object randomly and he would believe me, he would learn to act accordingly.