Stories that explain why the experimental writer Kim Hae-gyeong chose the pen name “Yi Sang” abound. Fellow avant-garde writer Park Taewon claimed that a Japanese supervisor had mistakenly called him “Mr. Lee” (Ri-san in Japanese), and Kim took up the name as a joke. Kwon Youngmin, a scholar of Yi Sang’s works, thinks he took the name in honor of a plumwood brush box his painter friend (and possibly lover) Gu Bon-woong gave him as a gift in college: the characters for “plum box,” 李箱, look like a proper name, Yi Sang. Those syllables are also homophones for the words “strange” (異常), “ideal” (理想), and “more than” (以上). Each origin story suits Yi Sang’s writings differently. His multilingual wordplay and untrammeled experimentation are certainly strange, highly conceptual, and always interested in more: more than reality, more than language, more than the present had to offer during his short life and troubled times.

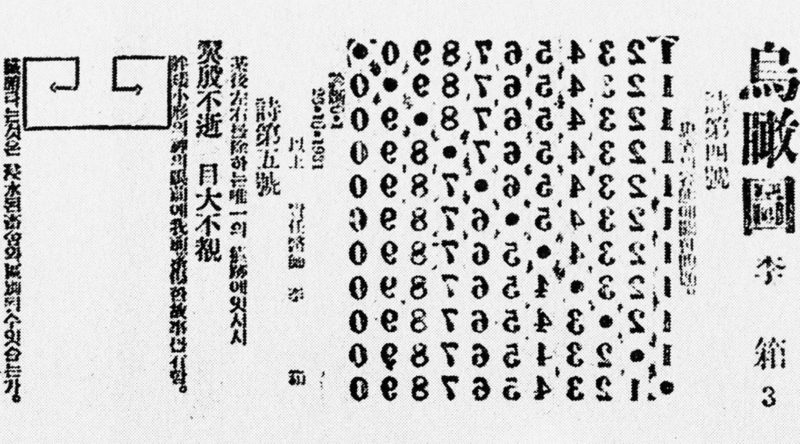

Yi Sang was born in 1910 and died at the age of twenty-seven of tuberculosis shortly after being released from a Japanese prison, where he had been held for the vague crime of being a “troublemaker Korean.” He only began to publish in 1930, but his brief career produced a body of fiction, essays, and poetry now viewed as the cornerstone of experimental writing in Korea and, with it, Korea’s place in the worldwide modernist movement of the early twentieth century. In his lifetime, he courted public shock with the strangeness of writings like Poem No. 13 of his series “Crow’s Eye View”:

My arm is cut off while holding a razor. When I examine it, it is pale blue, terrified of something. I lose my remaining arm the same way, so I set up my two arms like

candelabras to decorate my room. My arms, even though they are dead, seem terrified of me. I love such flimsy manners more than any flowerpot.

Yi Sang tried to publish thirty such poems—violent, surrealistic, brooding, antic—in the newspaper Chosun Ilbo in 1934. When bewildered readers complained, editors ended his publishing run; he raged against their philistinism, in a letter that was never published: “We are decades behind others, and you think it’s okay to be complacent? Who knows, I might not have enough talent to make this happen, but we really should be repenting for the time we’ve wasted dicking around.”

By Yi Sang’s time, over a decade after the violent Japanese suppression of a Korean independence movement, arguments over Korea’s literary progress were arguments over the future survival of Korea itself. During Yi Sang’s life, Korea was annexed by the Japanese Empire. If Japanese intellectuals fretted over “falling behind” and “catching up to” their European counterparts, Korean intellectuals—in a colony on the periphery of an empire that already believed itself on the global periphery—felt doubly belated. The blunt language of advancement and delay might strike us now as fraught, but Korean intellectuals had seen progress as linear for more than a generation before Yi Sang began to write. As early as 1916, the novelist Yi Kwang-su had staked Korea’s intellectual modernization on advancements in literary technique, writing: “From now on, we must create our first-ever legacy to bequeath to the next generation, by building a new and experimental literature that embodies Korean thoughts and emotions.” Yi Sang and his contemporaries strove to prove themselves no less “advanced” at literary experimentation than their counterparts in Japan and Europe. In the process, they expanded the technical and expressive ambitions of modernism into dimensions unimagined by its practitioners in the great imperial metropolises.

Yi Sang: Selected Works, edited by Don Mee Choi and translated by Jack Jung, Sawako Nakayasu, Choi, and Joyelle McSweeney, goes further than any previous English translation in providing readers with a sense of the historical context and political stakes of this enigmatic, often baffling writer’s aesthetics. While earlier efforts only provided excerpts, this volume presents nearly all of Yi Sang’s poems, translated from Korean by Jung and from Japanese by Nakayasu. Like most educated Koreans of his generation, subject to colonial education, Yi Sang was multilingual, fluent in Korean and in Japanese and acquainted with some Chinese, as well as smatterings of various European languages. Six of his most notable essays (translated by Jung) and two of his stories (translated by Choi and McSweeney) offer, in lively, swift prose, a sense of time and place in which to situate Yi Sang’s challenging poetry. Jung’s biographical timeline offers the best account currently available in English of the major events in a life that is difficult to reconstruct.

The book also offers modest but crucial selections of visual material, including photographs, sketches, design work, and reproductions of the original published forms of some poems. Yi Sang’s imagination was as dynamic visually as it was verbally: he trained as an architect and, at one time, exhibited his paintings, which have not survived. Many of his poems incorporate diagrams and configure Korean, Japanese, and Chinese script (with Latin, Arabic, and mathematical sprinklings) in striking rectilinear shapes. Wave Books has taken care to create typography and layout that echo the optical shriek with which Yi Sang worked so hard to jolt his audience.

Yi Sang knew that he was living through major transformations in the daily experience of time and space. His essays document the contrast between rural and urban life, from the disorienting din of Tokyo to the electrification and railroadization of provincial towns; for years, his most famous story, “Wings,” has been read through the lens of modernist flânerie. As part of cutting-edge circles in the world of visual design, he synthesized the innovations of the Japanese avant-garde with the new creative possibilities afforded by the rapid analysis and recombination of European art history and its many -isms. The illusions and confusions created by mirrors—bending and distorting light, multiplying images of silent, inaccessible selves—recur consistently in his work. He was sufficiently attuned to the scientific world to catch wind of Einstein’s novel theory of relativity and wrote a moving sequence of poems in Japanese (“Solid Angle Blueprint”) parsing the consequences of that new conception of time for human experience. From his “Memorandum on the Line 5”:

Escape to the future and look at the past, escape to the past and look at the future, or escaping to the future is not the same as escaping to the past and escaping to the future is escaping to the past. O those who grieve the expansion of the universe, live in the past, escape into the future more quickly than light…

The poem’s melancholy is simultaneously personal and historical. Yi Sang’s family had hoped he would continue its line; his uncle formally adopted him to ensure succession in the senior branch of the family, and Yi Sang graduated at the top of his vocational college class. But in 1931, the year he wrote “Solid Angle Blueprint,” a tuberculosis diagnosis threw a pall over his promising career. He sank into depression, chronicled later in his essay “After Sickbed.”

It was the same year Japan invaded Manchuria, using Korea as a staging ground. Modernity and modernization had moved in Korea at a vertiginous pace but at tremendous human cost, and under the violence of colonization. Korean literature, too, evolved within an accelerated modernity. Until the brink of the nineteenth century, vernacular Korean had not served as a language of state or high culture; for centuries, literati deemed Korean-language poetry lower in dignity than literary Chinese verse. Over the course of Yi Sang’s short lifetime, thousands of new Sinitic compounds formed by the Japanese to translate European technical vocabulary coursed into Korean, as did hundreds of European loanwords (including the term “modernism”). Magazines emerged in his childhood, and with them the phenomenon of serialized fiction and personal essays. The very texture of written language, including its orthography and grammar, was still in contest as he came of age. Korea’s nascent nationalism in the first decades of the twentieth century created an intellectual climate that bewailed the deprecation of Korean in the past and viewed the cultivation of a modern, Korean-language literature as crucial.

The flux of the Korean language and its literary forms in the early twentieth century poses formidable challenges to translators. Few writers availed themselves of all these linguistic options as imaginatively as Yi Sang. His writings are densely packed with words in hanja, Chinese characters used to write Korean words. He often titled his works with dense Sinitic phrases that sometimes open up a range of homophonic puns when read aloud in Korean. In his early Japanese-language poetry, he wrote indigenous Japanese words in katakana and loanwords in hiragana, flipping the language’s normal use of the two scripts to segregate foreign and domestic and thereby “normaliz[ing] that which would otherwise be delineated as foreign,” as Nakayasu writes in an insightful introductory essay.

This Yi Sang translation foregrounds the full variety of the author’s experimentation on the lexical level without stranding the reader. Yet the collection is avowedly, and welcomely, artistic rather than academic in style. The translators’ supplementary essays often enter a personal register, exploring their subjective and social positions in relation to Yi Sang’s work. They approach Yi Sang as a peer-practitioner rather than an object of research inquiry, an attitude which restores an edginess to his work lost in some earlier translation efforts.

Over eight decades after his death, Yi Sang’s influence on global literature has grown steadily through translation efforts, and he has become known as one of the most resourceful poetic tinkerers facing colonial adversity, material hardship, and political disfavor. He belongs not just with the likes of Gertrude Stein, André Breton, and James Joyce, but also Oswald de Andrade, Jean Toomer, and Aimé Césaire, writers who believed that the logic of the avant-garde need not be determined by patterns of economic or industrial advancement. Yi Sang’s artistic vanguard was ultimately wrought of a desire to shatter conventions of perception and feeling.