Miscellaneous Files is a series of virtual studio visits that uses writers’ digital artifacts to understand their practice. Conceived by Mary Wang, each interview provides an intimate look into the artistic process.

Laila Lalami’s oeuvre reveals a commitment to plumbing history’s margins and footnotes, and discovering in its shadowy depths people forgotten—and often erased. In imagining them anew, she gives back what was snatched away by force: their personhood, with all its richness and complexity. In her debut novel Hopes and Other Dangerous Pursuits, Lalami tells the stories of four harragas, Moroccan immigrants crossing to Spain. “The news was relegated to the bottom of Le Monde’s online page,” she writes, “—fifteen Moroccan immigrants had drowned while crossing the Straits of Gibraltar on a fishing boat.” Her Pulitzer-finalist historical memoir, The Moor’s Account, is based on the true story of a formerly enslaved man. Its narrator, Estebanico, is a Moroccan slave, one of only four survivors on the calamitous and once six hundred-person-strong Narváez expedition from Spain to Florida in the early sixteenth century. Estebanico was one the first outsiders to travel across America along with the three other Spanish survivors, only to have his eight-year experience reduced to a single line in Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca’s celebrated account, published when he returned to Spain. In reframing the narrative through Estebanico, Lalami assumes the role of truth-teller and fact-finder, chronicling the role of African and Arab explorers in shaping the New World, and questioning the whitewashed narrative that has endured for five hundred years.

In Conditional Citizens, her first book-length nonfiction work, she distills a long and storied career as a political and cultural commentator into eight essays that clarify and challenge our notions of belonging in America. In true Lalami style, the essays work as magnifying glasses trained on the fine print of citizenship, dismantling the asterisks that qualify people’s full enjoyment of Americanness—race, religion, gender, national origin. “Conditional Citizens,” she writes, “are people whose rights the state finds expendable in the pursuit of white supremacy.” They are policed and punished more harshly than others, they are not guaranteed the same electoral representation, are more likely than others to be expatriated or denaturalized. This curtailment—and even the outright violation—of their rights results in the maintenance of a racialized caste system, with the modern equivalent of white male landowners at the top.

I spoke to Lalami—she in California, I in New York—a few days after the nineteenth anniversary of 9/11, just as the summer was winding down and the country was gearing up to endure the grueling final leg of a marathon election season, during which the president would refuse to disavow white supremacy. We spoke at a time when this sovereign of sovereigns’ appalling treatment of the pandemic had isolated America on the world stage, nullifying Lalami’s once-giddy excitement at being free to travel to 150 countries with an American passport. We spoke about what it means to be American, to have a life shaped by a country thousands of miles away from your own, and the power to create a story.

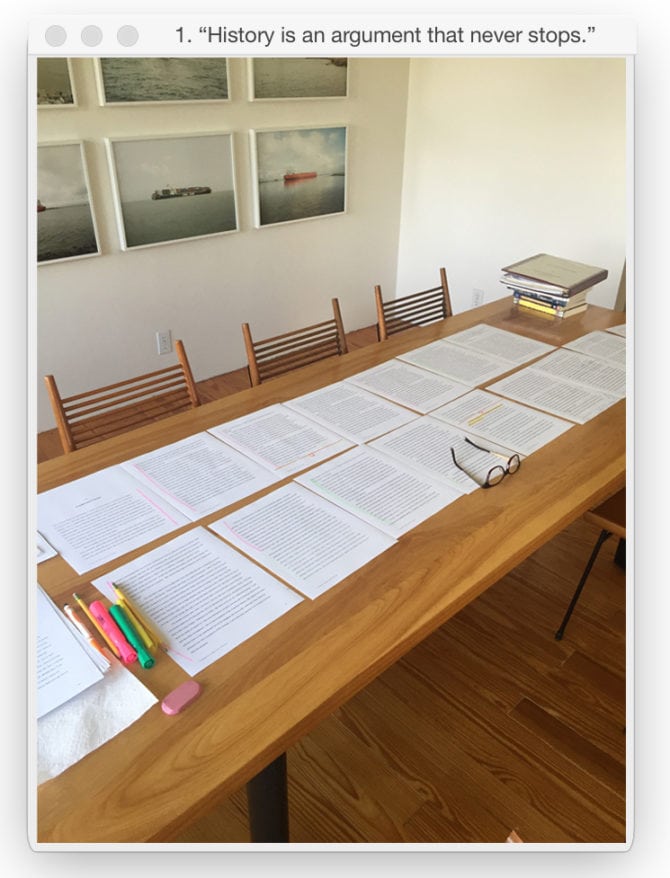

1. “History is an argument that never stops.”

Madhuri Sastry: This is your first book of nonfiction. Themes that run through your fiction—identity, belonging, history—are present in this work as well. What made you want to explore the topic of citizenship through a nonfiction framework?

Laila Lalami: Well, I’ve been writing nonfiction uninterruptedly for the last twenty years: essays, book reviews, columns and opinion pieces. I was always doing this on the side, while I was working on my novels. So there wasn’t a decision to go from fiction to nonfiction so much as that the only thing I’d published in book form was fiction. There came a moment when I wanted to put together a book of nonfiction. I just never got around to it because each novel takes so long—they’ve taken, you know, four or five years! Finally, I said: I can’t keep putting it off. And since I was pretty much done with The Other Americans, I decided to jump right into this one.

Sastry: How do you switch between the two genres?

Lalami: For me, they involve very different impulses. When I write fiction, it seems to me that I write at a very glacial pace. It requires a lot of trial and error, writing scenes and deleting scenes, writing characters, taking them out. Fiction involves a lot of explorations. And it also involves, crucially, withholding judgment—in the sense that the people that appear in my fiction are treated as characters that I’m trying to make as compelling, real, and complex as possible. That means I have to withhold judgment and try to inhabit these characters as fully as I can, as fully as my imagination allows me. I write about people who are often very different from me, and I have to write about them very empathetically. Conditional Citizens is very different from the novels because I’m much more present on the page. It’s funny, I constantly get asked how much of me is in my novels; so now, finally, people are going to get at least some glimpse of me in this book, which I’m not used to. My biases, my preferences, my political analyses, my perspective, my experiences, all of those things are more apparent on the page. On top of all this, there’s a lot more judgment. When I write about one of the politicians in the book, I’m not going to say that I write about that person without judgment. That’s very different from how I would write if these people were in a novel.

Sastry: Did you think of yourself as a character when you were weaving yourself into your analyses?

Lalami: Not so much a character as a narrator. The book is the result of some thoughts that have been swirling around in my head about citizenship for a long time, and it was an opportunity get them down on the page. In this picture, I was in Marfa, Texas, on a writing residency. I don’t remember what chapter this was. I was basically laying out the text on the on the table and looking at different portions of the essay, portions that have to do with the personal anecdote that launches the essay and portions that have to do with background and history. And the color-coding was a way for me to keep track of which section was doing what, and taking notes on each for revision.

Sastry: In the opening chapter of Conditional Citizens, you write about a post–9/11 shift in the way you and your citizenship were viewed. It’s the nineteenth anniversary of 9/11 and I want to talk about the importance of this moment and this Paul Krugman tweet, where he says, “Overall, Americans took 9/11 pretty calmly. Notably, there wasn’t a mass outbreak of anti-Muslim sentiment.” He got called out, appropriately, for being a historical revisionist. With all of the literature, poetry, and stories that now exist about the experiences and lives of Muslims in a post–9/11 world, how can a narrative like Krugman’s exist in the American mind?

Lalami: I think that narrative exists because it provides comfort and consolation for people like Paul Krugman. Obviously, he’s a Nobel-winning economist, he writes for the New York Times, he has access to massive amounts of data and analysis. He even has access to the voices of Muslim Americans and Arab Americans and others who have been affected by 9/11. To have a view like that in spite of all the evidence to the contrary means that—I suspect—there is some kind of consolation for him in thinking that way.

He is clearly remembering these events in a way that is different from the way the rest of us are remembering them. It is a little bit frightening, to be honest, because it shows you how historical erasure happens in real time. When people who are by all accounts part of the elite—Paul Krugman is not just some rando with a laptop, this is an eminent professor and economist and columnist—have that memory, it is very sobering, but perhaps not entirely surprising.

I know everybody was piling onto Krugman for what he said, but this is something that is ongoing in the United States. Look at somebody like George W. Bush—he started two massive wars we are still living with today, the war in Afghanistan is now nineteen years old, tens of thousands of people have died there and hundreds of thousands have died in Iraq—but this man is now being rehabilitated just because Donald Trump is president. So many liberals are saying that things weren’t as bad during George W. Bush as they are under Trump. And that’s definitely not true. But with the passage of time, you see that some people forget what happened because it didn’t happen to them. It didn’t happen to their family members; the pain was not theirs. And so, people like Krugman and others who are so busy rehabilitating David Frum, Bush, and all of these people who were responsible for these wars, are people who in most cases haven’t suffered from [what they did].

Sastry: In The Other Americans, your characters are people whose stories aren’t considered quintessentially “American.” I wanted to extend that net a little bit and talk about those who come to America with a very different experience of American history from those who have been here for generations. So many immigrants come from places that have borne the brunt of American foreign policy decisions, but that’s an American history we don’t hear. Do you think those types of stories will ever be considered a part of American history? Will the story of a kid growing up during, say, the American occupation of Afghanistan ever be as American as apple pie?

Lalami: I think that history is an argument that never stops. When I look at the experiences of people like that and people that I know who have gone through experiences like that, those are very real experiences, and people have tried to record them. But whether they reach wider audiences, whether they are taught to generations of people, those are forces that few of us control. It really depends on a number of things, like who wins the rhetorical argument, who is in charge of the textbooks that students are reading. There are all these forces that decide for us what kind of history we’re taught.

Sastry: Do you think that the pandemic has created a shift or an appetite among people who have been kept away from power to come forth and tell their stories?

Lalami: We all have the hunger to tell our stories, and I think that the pandemic—because it has created such a far-reaching economic and health crisis—is really forcing people to pay attention to what has been going on around them. Take Black Lives Matter: Black lives mattered six months before the pandemic, six years before the pandemic, and six hundred years before the pandemic! The desire to be heard was always there. Whether the pandemic will result in actual or significant change, I don’t know. It’s too early to tell. But the desire for justice is very deep. And I do know that we all have a hunger to have our stories heard and have our stories recorded. Whenever I talk about the history of Muslims in America, for example, people are always very curious. They want to know more. But obviously it’s not something that is taught widely in in schools.

2. I don’t think the families of these goofy kids on a balcony could’ve predicted that all of them would become immigrants.

Sastry: Tell me a little bit about this beautiful photograph of you and your family.

Lalami: Can you tell which one is me?

Sastry: I think you’re the little girl in the green and white dress!

Lalami: Noooo! I’m the one in the blue gingham dress! Those are my siblings and three of my cousins. This is on the balcony of either my parents’ apartment or uncle’s apartment. It’s before we moved and is in a different part of the city than the one I grew up in. I sent this photo because everybody you see in it now lives in the States, and none of us could have predicted that. Everybody ended up here for different reasons and through different paths. When I look at it, it reminds me that you really cannot predict the turns that your life is going to take.

One of the things I wrote about in The Other Americans is the unintended consequences that take place years after having made a particular decision. In that novel, a couple leaves Morocco after the husband has gotten into some political trouble; the idea is that they’re going to start over in the US and find a life of stability and safety. On the first page, you find out that the father has been killed in a hit-and-run accident. The couple has a daughter and when they moved to the US, they have another daughter. And so there are all these different consequences to their decision to move, and it culminates with his death. That was something that I always wanted to write about because I never really intended to come and live in the US. I came to go to graduate school, and before that, I had studied in England. And before that, I studied in Morocco, and the idea was to finish my degree and become a college professor. But after I moved to LA, I met someone, and we got married and I became an immigrant! It really was chance, or at least I thought it was chance.

But when I look back at the path that my life has taken, I can see certain sign posts along the way that indicated that I was going to end up exactly where I ended up. For example, when I was in high school you could take a second foreign language. I was bilingual, Arabic and French, and so I took English as a third language. By the time I finished high school, instead of applying for medical school, I ended up deciding to study English as a major in in college. So that decision to take that foreign language in high school led to a decision to major in English in college, which led to a decision to apply for a fellowship in England, which eventually led to a decision to finish a PhD in linguistics. And that’s what brought me to LA. And that is how I met my husband. When I look at the ripple consequences of decisions over the years, it’s really interesting to see how a life can take a particular path and not another. And I don’t think the families of these goofy kids on a balcony could’ve predicted that all of them would become immigrants.

Sastry: At what point in the writing of Conditional Citizens did this photograph feel most relevant to you?

Lalami: When I was writing the short sections that take place in Morocco that have to do with growing up there. And then again for the chapters about borders and assimilation, and how your life can take these unexpected turns. Immigration is often talked about as something that changes your life, and that’s true. But even under the best of circumstances it’s not necessarily an experience that is easy or always positive. When I look at that photo, I see the possibilities—the possibility, at least—of a different life. If I hadn’t come here, what kind of life would it have been?

Sastry: You mention in your book that you worked at a progressive newspaper in Morocco. Was that an English language daily?

Lalami: It was a French language newspaper. Believe it or not, I actually wrote nonfiction in French way back in the day!

Sastry: Is the experience of writing in English different for you from writing in Arabic or French?

Lalami: I suppose that it is, because writing in English was something I did first out of necessity when I was doing my PhD: all the articles, the academic work that I was doing was in English, and this is very, very dry academic work in linguistics and psycholinguistics. It wasn’t at all what we think of as nonfiction or creative nonfiction; that came later. It’s a language that, for me, was a work language, an academic language that you use for research purposes. But I had always written—I’ve written since I was a child—so when it dawned on me that I was going to stay in the US for a while, I thought maybe I could try writing some nonfiction. I had seen something that was very upsetting—something about stereotypes in Hollywood—and I wrote a very angry Op-Ed and sent it to the LA Times. And that’s how it started, with little pieces here and there, until I wrote books. Life takes turns; that is the theme here!

Sastry: Do you ever feel a sense of loss when it comes to Arabic or French?

Lalami: Not with respect to French whatsoever, because it is a colonial language. It’s a beautiful language that I have nothing against, but it’s not something I feel emotionally attached to. I do feel a sense of loss in terms of Arabic. My parents sent me to a French grade school and we didn’t get as many hours as we ought to have received for learning Arabic. I was never really taught properly. And then by the time I got through school, I felt I was always a little bit behind. But it’s fine. I teach it even, now! But in terms of having to actually write an entire book of fiction, that wasn’t something I felt proficient enough to do. So there is a sense of loss, not just in terms of the language, but also in terms of life. Even if you have a very positive immigration story it will, by necessity, involve loss.

3. I have to be organized to write books.

Lalami: Every year in January, I get a notebook. It’s a weekly planner. On one page it has the days of the week, and the page opposite is for notes. And I use this—this is going to really make me sound crazy—I use this every day when I write to record the number of words.

Sastry: Oh, wow!

Lalami: I know! I’m sorry, I’m sorry! I’ve had one like this for the last 20 years. For each day, it’ll say “novel,” for example, and then 1200 words. And then the next day, let’s say, 200 words. And then the total will have 1400. All the way like this, over years and years, until I get to the magic number at the end. I think The Moor’s Account was like 126,000 words, so that was five years’ work right there. This last one, [Conditional Citizens] was just a little over 100,000. It’s to keep me going and see how many days I have actually gotten any writing done. And at the end of the book, I usually just write the titles of books I’m reading.

Sastry: You are super organized!

Lalami: I try, I try! That organization is a necessity, because I’m also a professor. I have to be organized to write books.

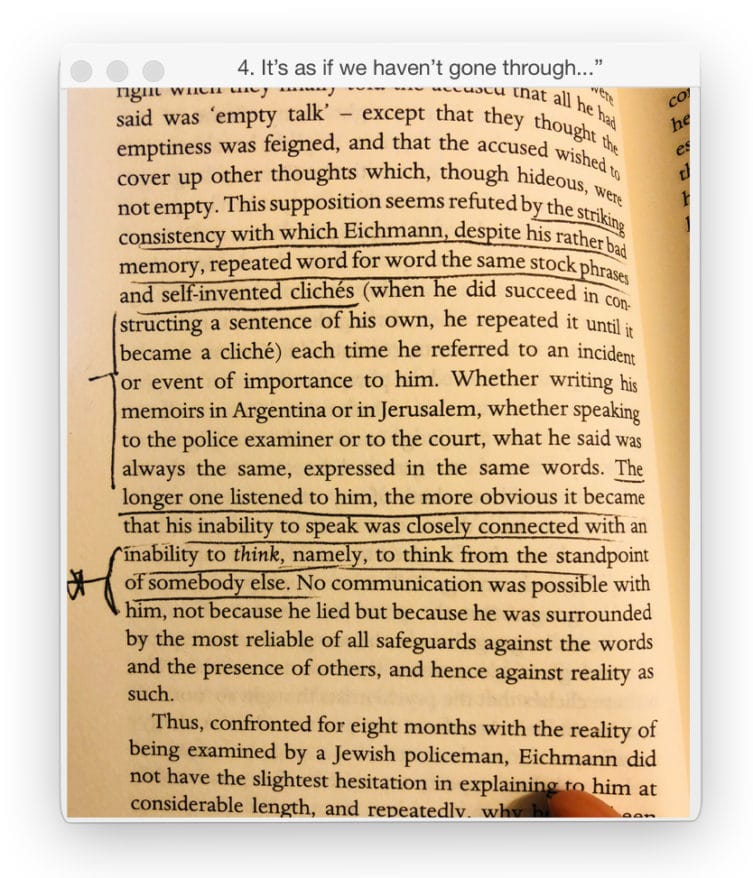

4. “It’s as if we haven’t gone through the last fifty years of history.”

Lalami: When I read books or do research or when I’m working on a book project, I maintain notes. This was during the writing of the Conditional Citizens, and it’s Eichmann in Jerusalem by Hannah Arendt. When I’m reading a book, I’m just underlining. And when I’m done with it, I go into my notebook and write out what I think about it, what works, what doesn’t work, plus quotes or anything else that stands out to me.

Sastry: When I read this passage, the first person I thought of was Donald Trump. Is that representative of the American immigration system—the inability to think from the standpoint of someone else?

Lalami: I don’t think it’s specifically American. I do think that it’s specific to fascists and demagogues. They think that what they think is the only way to think. It’s a very dangerous approach. When you look at it—particularly this year, surrounded by so much rhetoric that reflects exactly this—it’s something I wish more people were paying attention to. One of the things I’ve seen in so much writing is that human nature doesn’t really change. So, back then, while they’re listening to this guy [Eichmann], they couldn’t pick out that he was basically repeating the same stock phrases and that there really wasn’t any kind of reasoning there. And human nature still is the same today. It’s as if we haven’t gone through the last fifty years of history.

Sastry: That ties in well with the passage that you sent me from the New Orleans lynching [not pictured here].

Lalami: In writing Conditional Citizens, there was a lot of research into different elements of American history. When you look at this particular incident you see how Italians were accused of bringing in the “lawless passions” of their country and contaminating America with their foreign and violent ways. It really is incredible how similar that is to the rhetoric being used today with different groups of immigrants. Right? And just look at the paper that published it!

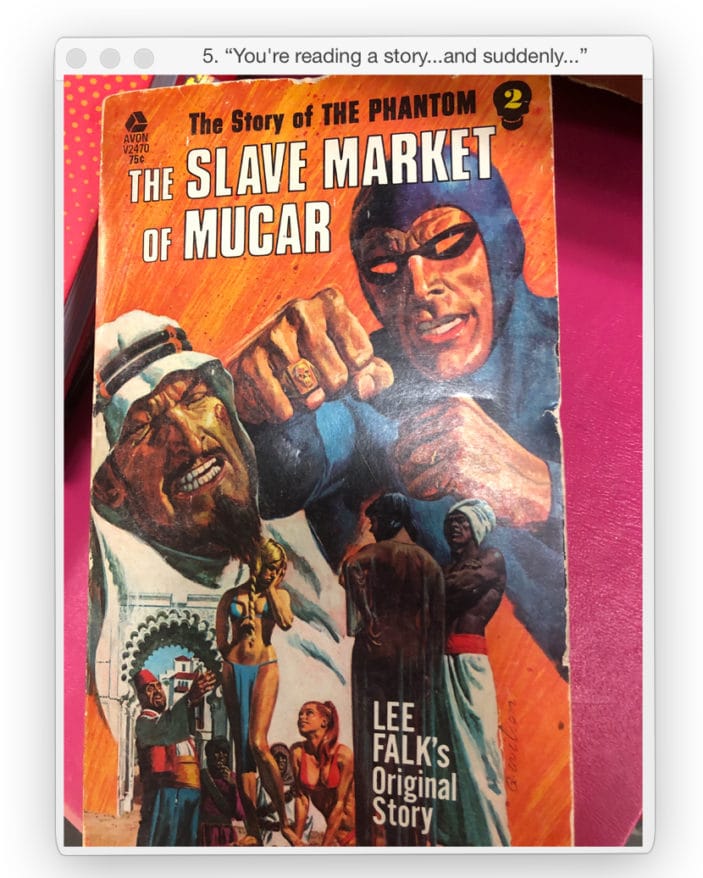

5. “You’re reading a story…and suddenly you realize that you were the villains in this story.”

Sastry: Why did you select this?

Lalami: I was at a used bookstore in Joshua Tree, I think. I was browsing and saw this, I think it’s some kind of a fantasy book. I was looking at the guy who is the villain with his beard and the white woman that everybody’s trying to, I suppose, turn into some kind of a sex slave. She’s being sold in the slave market. The art is vaguely Moroccan and there’s the Nubian gentleman on the right. It’s a mix of Orientalist images, and I took a picture of it.

I did that because I was trying to replicate an experience known to a number of people who were not part of the racially dominant, politically dominant group experience—which is, you could be reading any book, and there comes a moment where you come across something incredibly stereotypical or offensive and suddenly you are thrown out of the narrative. You could be watching a movie, and the same thing happens. Somebody makes a racist joke or an Islamophobic joke. There’s no warning when you experience that moment where you realize that whatever is being written is not being written for you, but it’s written about you for other people.

I wanted to remember the moment I came across that, because it is something I have lived with all my life. This feeling, that you’re reading a story—you could be in a sci-fi story, you could be in fantasy, or you can just be in contemporary fiction—and suddenly you realize that you were the villains in this story. It’s very sobering and always a shock. This is one of the reasons why I think, “Who am I writing for? Who is included in this writing and who is not included?”

Sastry: You mention in the book that the person who swore you in as a citizen told you that citizenship is a privilege. And that is the way we’re taught to think of citizenship: as a privilege. Is now a good time to rethink it—not as a privilege, perhaps, but as a right that can never be taken away from you?

Lalami: First of all, it’s very, very important to understand that citizenship is completely arbitrary. Where you are born and the country of your citizenship is essentially a lottery. You can be a US citizen, or a citizen of pretty much any other country and you have no control over that. The only people who do are people who naturalized: people like me. I did choose to be a US citizen. But one of the really disturbing parts about it is that even within the boundaries of US citizenship, there are arbitrary elements. Your race can affect how your rights are lived in the US: I don’t think I need to give you any examples of that, you just have to turn on the news, right? You can see how a police encounter can end very differently, depending on the race of the person who has encountered the police. Race, gender, those are all arbitrary things. None of us control them.

One of the things that comes across in the opening chapter of Conditional Citizens is that we often think of citizenship as a status: You either have it or you don’t. The judge who swore us in thought of it as a privilege that was being bestowed upon us. But what if we thought of it not so much as a status but as a relationship: a relationship that ties one citizen to other citizens, and the citizen and the state? If we think about it as a relationship, then it’s something to be nurtured, something where you understand that you have to give and you have to take, and your rights are tied to the rights of others. We have to think about citizenship as a relationship. And it has to be treated with care. Through care for other citizens, in other words.