“In my family, country music was foremost a language among women,” writes Sarah Smarsh in She Come By It Natural, her new book on the lyrics and legacy of Dolly Parton. “The two women who raised me, my mom and grandma, cared a great deal about music that validated the stories of our lives.” That music included, at the top of the tape stack, Dolly’s.

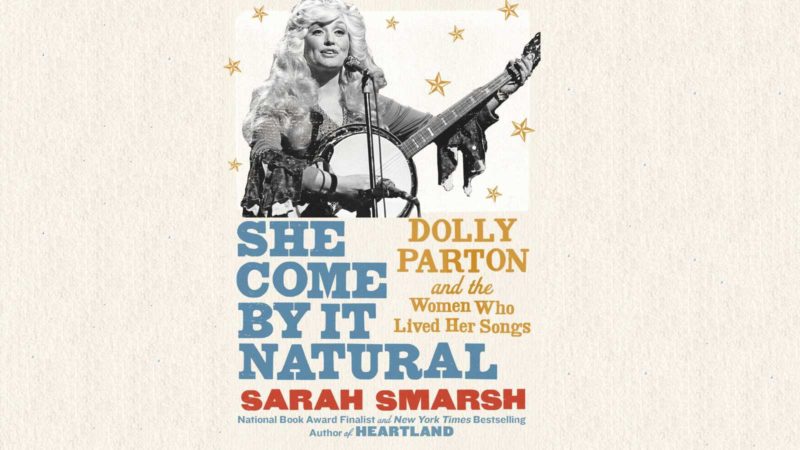

With She Come By It Natural—which is part cultural criticism, part biography, and part memoir—Smarsh adds a welcome voice to the recent cascade of Dolly-centered analysis and hero-worship, some of which takes for granted the fact that Dolly has been Dolly-ing for fifty years. A lot of the newer chatter can be traced to women in my age bracket (late twenties-early thirties), the same group whose relatively recent conversion to the church of Dolly is responsible for the “cup of ambition” coffee mugs and Etsy-order prayer candles with her face on them. But Smarsh, whose previous book Heartland tells her story of growing up poor in rural Kansas, can’t write about Dolly without writing about Betty, her own grandmother, who is around the same age as Dolly (seventy-five), and who began hearing herself in Dolly’s lyrics many decades ago.

Smarsh describes Dolly as a “transcendent storyteller,” a megaphone for the women she grew up around in the Great Smoky Mountains. Her family was large and loving, poor and religious, without much formal education (her father couldn’t read or write); Dolly may have “gotten out” of East Tennessee, but her songs remain firmly rooted in those foothills. Particularly in her early songwriting years, when she leaned most heavily into the narrative and gothic Appalachian ballad tradition (writing what she calls her “sad ass songs”), she shed a spotlight on women whose particular sets of circumstances involved rural poverty, political disenfranchisement, and feminine pain. “He’s been gone so long/When he left the snow was deep upon the ground,” Dolly sings in 1970’s “Down From Dover,” “and I have seen a spring and summer pass/and now the leaves are turning brown.” The character at the center of that song—a pregnant teenager who has been abandoned by her baby’s father, who faces rejection by her conservative community, and who, in her sadness, miscarries—is at once archetypal and lived-in, a universal stand-in and an individual, like so many women of fables. Like so many women given voice by Dolly.

“That darkness in a woman’s voice, plain stories of hell on earth sung by women who have little to carry them forward but faith, is the divine feminine of American roots music,” Smarsh writes, and it’s plain that witnessing oft-neglected pain is an important, political act. Smarsh brings in some of Betty’s own experiences here: by the time Betty was thirty-two, she had left six husbands, many of them abusive (“the first one shot her. The second one kidnapped her son. The third one broke her jaw…”). Without ever having heard the term “patriarchy,” Betty “knew that she wouldn’t let a man, town, or boss mistreat her or her children”—so she left when she had to.

Betty’s life wasn’t all darkness, though, and neither are Dolly’s early songs. That’s equally important: because they echo what she grew up around, the diversity of a real place, Dolly’s women characters refute the idea that “rural women” are a monolith or easily categorizable, even while the lyrics validate shared experiences. Sometimes, Dolly’s women are telling men off for mistreating them (“You’re Gonna Be Sorry”) or voicing their frustrations around gender disparity (“Just Because I’m A Woman”); other times, they’re walking down the road and falling hopelessly in love with the town misfit (“Joshua”). They’re sometimes tough and world-hardened and funny (“I’ll Oilwells Love You,” about a woman who schemes to marry a rich Texas oil man for his money, is definitively not “I Will Always Love You”). Other times, they’re in awe of the little things, the honeysuckle vine that “makes the summer wind so sweet.”

In this way, Dolly champions the humanity of “[a] frequently vilified class of American woman…otherwise voiceless in society,” in Smarsh’s words. On “Dolly Parton’s America,” the Radiolab-produced podcast about the singer released last year, Helen Morales calls this same impulse Dolly’s “insistent witnessing of women’s lives.” In later decades, Dolly moved away from her narrative mode of songwriting and toward more direct messaging about women and power; this, of course, is when the working woman’s anthem “9 to 5” came into being, not to mention 1989’s hit “Why’d You Come In Here Looking Like That” (that video found Dolly sitting on a judging panel, determining who among a lineup of auditioning men best fit into his jeans).

While this very act of witnessing—the rather serious way, even in the most unserious videos, she prioritizes the female perspective—is a key piece of the Dolly puzzle, it must not be ignored that almost all of the women whose lives Dolly directly “witnesses” in her songs are white. Dolly does not engage in frank acknowledgments about the existence of racial injustice often (this is something Smarsh notes, though too briefly: “[Dolly] has taken bold stands for the LGBTQ community, for women, and for the poor,” she writes. “Her statement on all the rest, from race to political affiliation, has remained a message of love in general terms”).

Smarsh, in one of the book’s most intriguing moments, talks about the Dolly brand of feminism as organic—something she believes Dolly and the women who inspire her lyrics “come by naturally.” According to Smarsh, this is something that has less to do with a movement and everything to do with simply existing in the world (living, but also surviving). “[Dolly’s] politics occur at the human level, examined as experience rather than abstract concepts,” Smarsh writes, “and lived directly rather than bandied in academic terms.” The way that Dolly lives now no longer speaks to the politics of surviving, of course, but it does speak to this idea of life-as-feminism. It was a self-reliant choice for a bright and ambitious eighteen-year-old Dolly to board a bus to Nashville to pursue stardom; it was her smarts, her expert industry maneuvering, that allowed her to become chart-dominant for decades. The compromises she made were active ones (like doing The Porter Wagoner Show, on which she reports having felt largely ornamental), as were the things she wouldn’t budge on (like not giving Elvis the publishing rights to “I Will Always Love You,” even though it meant he wouldn’t cover it). In the later years, she’s brilliantly leveraged all her staying power into a financial empire, which even includes a theme park.

There’s also the masterful way she manipulates her public persona. From the start, Dolly carefully modeled her signature look off an unnamed “town tramp” she’d seen as a child—a purposeful, reactionary choice because, as Smarsh stresses, feminine sexuality was hard to embrace in the time and place in which Dolly grew up. The aesthetic universe Dolly has built for herself is able to contain both her sexuality and her religious roots, neither of which, in her eyes, imperils the other. She usually rejects making hardline choices of that nature: she told host Jad Abumrad on the podcast that she “think[s] like a man,” before adding, “but I think like a woman, too” (meaning, in the binary rhetoric of an older moment, that she is able to be both coldly rational in her business dealings and deeply sentimental in her songwriting). She rejects the idea that her altered body makes her “fake” (“They’re real big, they’re real expensive, and they’re really mine now”); and, with similar linguistic dexterity, she has long steered herself around political conversations, knowing well that her fanbase is as red as it is blue.

“Maybe it’s no coincidence that Parton’s popularity seemed to surge the same year America seemed to falter,” writes Smarsh, referring to 2016. “A fractured thing craves wholeness, and that’s what Dolly Parton offers—one woman who simultaneously embodies past and present, rich and poor, feminine and masculine, Jezebel and Holy Mother, the journey of getting out and the sweet return to home.”

It has certainly always struck me that complex or even contradictory women have an “organic” feminism in their very selves, though I had never framed it this way before reading Smarsh’s book. Women who allow themselves to inhabit gray spaces, to be un-straightforward or imperfect, are rejecting a demand that they neaten their narratives, become legible or palatable. Perhaps Dolly or Smarsh’s grandma Betty would conceive of “complexity” as savvy, a smart girl’s way to navigate a world of double binds. Either way, the broader culture and feminist discourse have only recently caught up on this: now, the younger liberal women I’m surrounded by seek out post-post feminist icons who are messy and “real,” or who display a convergence of traits once considered totally incompatible (emotional vulnerability and financial ascendency, for example, or sharp intelligence and hyperfemininity). Dolly has, for five decades, been sitting at the forks in many roads.

On “Dolly Parton’s America,” Abumrad brought up feminism outright. “Do you think of yourself as a feminist?,” he asked Dolly, to which she answered, without missing a beat: “No, I do not.” This may be a predictable stance from a woman who firmly distances herself from politics, and whose multiple identity markers (her formal education level, the socioeconomic class and the geography she inherited by birth) make it likely for her not to feel represented by a disproportionately coastal and college-educated movement. “The idea of Dolly Parton: The Feminist…bugs you in some way?,” Abumrad tried again. “Well that word…,” Dolly replied. “When you say ‘feminist,’ it’s just…like, everybody goes to extremes sometimes. I do not like extreme things.” That Dolly thinks of feminism as “extreme” may be a product of something definitional, or something generational. But what’s frustrating about this taped moment—Abumrad’s insistence on framing the conversation with a “yes” or “no” question—is that it offers Dolly little room for the nuance she seeks out and embodies.

Smarsh appeared on “Dolly Parton’s America” to provide her perspective on this issue, and she differentiated, then, between feminists “in theory” and “in practice.” Her analysis did some work to correct that interview moment (and Abumrad did take his conversation with Smarsh back to Dolly, who liked the idea of feminism “in practice”). But in her book, Smarsh goes even further: “Parton does not identify as a ‘feminist’ and, like me, comes from a place where ‘theory’ is a solid guess about how the coyotes keep getting into the chicken house,” she writes. “But her work is a nod to women who can’t afford to travel to the march, women working with their bodies while others are tweeting with their fingers.” These are the women for whom the movement has not always been accessible, but who have long been embodying its tenets in their day-to-day lives. With her concept of a natural kind of feminism, Smarsh names the “overlooked, unnamed sort of feminism” in both Dolly Parton and “in the hard-luck women who raised me…There was no feminist literature or theory in our lives. There was only life, in which we were women.”

Something about this cleaving, though very satisfying, feels not entirely spotless to me. First of all, a feminism that clings completely to your own lived experience is hard to extend to the lived experiences of others. That might present an enormous drawback—and it has even for Dolly, as with her blind spots on the importance of overtly naming and discussing issues of race. Second of all, though feminism thought about and feminism lived are important categories to distinguish between (especially in light of the relevant class discussion), I’m not sure I buy they have no common ground. The personal is ever-political; that would seem to blur, or at least soften, the hard line Smarsh draws.

More than anything, I think the fact that Dolly’s life’s work adds up to a feminist contribution—even if it’s not always engaged, explicitly, in feminist messaging; even if she, herself, won’t claim the term—makes it part of the feminist cause. The paradoxes Dolly personally embodies push us toward a feminist understanding of her, and Smarsh even runs into a Dolly logic paradox of her own: at different times, she insists Dolly’s music is not feminist in an academic sense, and writes that “country music by women,” including, importantly, by Dolly, “was the formative feminist text of my life.”

This, though, is what’s best about Smarsh’s book: how much it gives us to chew over, its deeply personal point of view, and its insistence—a lot like Dolly’s—on holding seeming opposites simultaneously. That Dolly lives and tells a certain kind of story says more about her value system than any single word could, no matter how badly I may long to hear her say it (and I do. I long to hear her say it). Her life is rich and complicated; her songs are governed by women’s experiences and feelings, largely those from a pocket of this country not spotlighted enough. Those are political things, and that’s the point for Smarsh, I think. It’s the point for me, too—that women’s lives, exactly and imperfectly as they are lived, wherever they are lived, simply matter enough to constitute a sonic heartbeat.