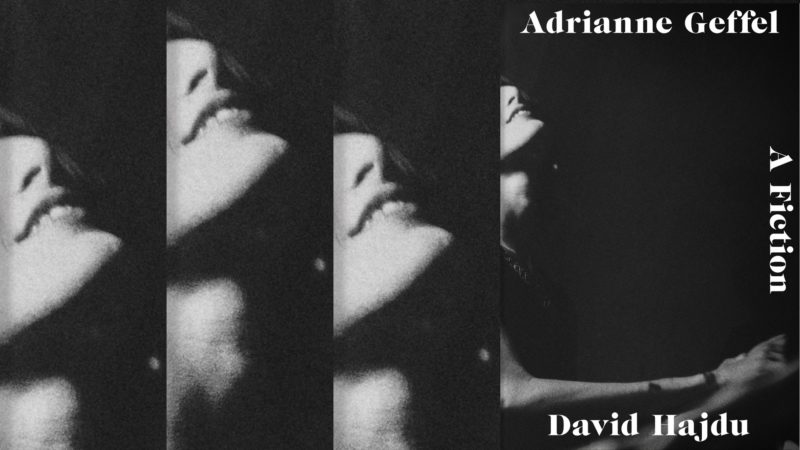

“Her records are a free assault on everything that recording itself represents,” notes a fictional Village Voice music critic in David Hajdu’s novel Adrianne Geffel. He’s referring to the title character, a virtuoso pianist whose avant-garde improvisation rocks the lofts of 1970s SoHo. And he means it as a compliment, recalling “outbursts so vital, so mind-rattling, soul-fuckingly extreme that they burst out and fly straight through you and out of your room.” The novel purports to be an oral history, driving home Adrianne Geffel’s cultural impact by referencing records that had to be heard to be believed, an unauthorized semiautobiograpical film, even an eponymous verb, to geffel (meaning “to release pure emotion in a work of creative expression”) and her mysterious disappearance, unsolved to the present day. The odd historical reference aside, Adrianne (and every other character “interviewed” for the book) is a figment of the author’s imagination. Together, these interviews form a postmodern account of a postmodern pianist, an outspoken chorus in which her own voice is absent, at once obscuring and illuminating her.

Hajdu, himself a reviewer of music, movie, comics, and culture at large, brings a kind of comic book sensibility to his first novel, which resembles a music biography. Though relatively short, the book is heavy on illustrative details and quirky pulp sensibility. Unfolding from the perspective of a faceless oral historian interviewing a series of subjects, the point of view is disciplined in a way that recalls a comic book penciler’s control over a panel’s field of view.

Like a traditional biography, the novel starts in Adrianne’s early childhood and proceeds chronologically through her life. As a baby she hums complex original melodies, yet the slightest musical phrase— an overheard radio, a live instrument, even recordings of her own voice—send her into a fury of atonal, violent rhythms. Her parents, who are wholesome if not especially culturally literate (“I love movie musicals, even when they’re on the stage,” says her mother, about a class trip to Broadway), are perplexed by their child’s mercurial rages. Slowly, her teachers and friends realize that Adrianne is reacting to music she hears in her head, music that reflects her emotions. When sounds in the real world are discordant with that music, the dissonance forms a feedback loop that makes watching a movie or attending a school dance a traumatic experience. But why? Everyone in the book has their own hypothesis: Geffel’s parents speculate about her baby formula, and the propane tanks they stored above her bedroom. Her teachers believe that if they could only give her the right environment, the right resources, her potential could bloom. Her doctors diagnose her with psychosynesthesia and consign her to music therapy as a cure. Her aunts, meanwhile, believe she is possessed.

Adrianne is introduced to the city through the prestigious, imperious world of Juilliard, presented here as an old boys club for those of a certain social status. (As for campus life, the students were simply “required to practice their instruments, and beyond that, to be breathing.”) Adrianne’s time studying piano is cut short when, at a recital, she plays harsh atonal melodies instead of the sheet music in front of her—a manifestation of her emotional discomfort—and is sent to a mental institution. There, she meets a conceptual artist, and, upon her release, springs onto the music scene, playing uprights in art galleries and grand pianos in lofts where she is hailed as an avant-garde hero. Her music reflects the stress of performing in an alien world, the emotions manifesting in an eruption of nervous sound. This style becomes Adrianne’s hallmark and brings her fame—but none of the people around her consider how this intensity might impact her mental health. One of her few true friends, a conceptual artist who goes by the name Ann Athema, observes that in a performance “Geffel was terribly nervous, and that only made the music more…like Geffel’s music.” It is in Ann Athema who Adrienne confides about the internal torment that leads her to perform the music she does. “I’m a nervous wreck when I’m doing it, and that only seems to make it more successful. I feel awful, and so I make awful-sounding music,” her friend recalls her saying.

With the wisdom of hindsight and curated narration, we see how the people around Adrianne ignored this strain, leaving her vulnerable to a fellow Juilliard student–turned music producer who exploits her talent and corrals her into a pseudo-romantic relationship. We witness her father’s standoffishness, and her mother’s inability to help her daughter navigate the world. Meanwhile, Adrianne’s classmates and instructors care more about promoting themselves than they do about her wellbeing. A doctor who treated Adrianne uses the interview as an opportunity to plug his book, as does her piano instructor, and the music critic who’s seeking a publisher for a collection of his reviews of her work. In the same vein, several characters all claim to have discovered Adrianne, or to have created her. As one critic puts it, perhaps mirroring a phenomenon Hajdu has observed in his own work as a critic, “Since her music was so unique and stood outside the standard categories, writers on every music beat felt free to grab a piece of her….The arrogance was appalling.”

Barbara Lucher, Adrianne’s high school best friend and later romantic interest, acts as a kind of counterbalance to these unrepentant pedagogues. Teaching her how to block out the music of the world with earplugs and scarves, she protects Adrienne, and helps her have a normal-enough high school experience. Later, they move in together, lofting their bed over a piano and joining the “big lesbian hangout” of the Village. With Barbara around, the music in Adrianne’s head is gentle, lyrical, and soothing. But the critical establishment of the time—a group of (notably all male) producers, reviewers, and critics—declares that the music she produces during that happy period isn’t radical or avant-garde. These critics believe that her music, a mirror of her emotions, is only good when she is struggling. Though she is far from the first artist to wrestle with fame, Adrianne’s distinctive musical abilities, and the emotional transparency of her music, make these tensions uniquely visible. Hajdu’s book can be read as the story of a critic grappling with the destructive forces at play within his own field.

After seven years of performing in Manhattan, Adrianne makes the choice to leave. Skipping a career-defining recital at Carnegie Hall, she disappears. But, remembered as a musical oddity, a pure emotional force, an icon, it’s hard for the music world to let her go. The closing pages of the book consist of a bulleted list of theories about where she is now, culled from listservs and Twitter, each more outlandish than the last. Adrianne is rumored to have started a farm, performed in a mask and cloak under a different name, started a band called Monkeyz using digital avatars, or moved into Laurie Anderson and Lou Reed’s back yard. Talked down to, manipulated, written off as possessed and mentally insane—is it any surprise that Adrianne Geffel opts out? In the end, Adrianne Geffel is both a love letter to cultural criticism and avant-garde art, and an intimate indictment of the same.