Every morning, after my laptop boots itself awake—gearing up at an easy, breezy 2010 pace—I find myself returning to music I listened to yesterday, my fingers retracing their keyboard jabs back to the same album or playlist. Like a homing pigeon, I’m pulled back to one particular place, and like a migrating animal, the location changes every season or so.

I think this instinct to set up base camp inside the same music for months at a time is a corrective to my brain’s general state of hyper-wiggling. I have a tendency to vacillate, wide-eyed, in the abundance of all the music. Part of my brain is greedy! There has never been more music available, it insists, and I can’t afford the luxury of repetition! It’s probably best to dash around, to get a snippet of everything in the anachronistic whiplash between eras: a new single from my favorite avant-garde neo-soul empath (typical), a Bach moment (ha), Normani on repeat (forever). Best to splash happily in the cultural aesthetic of saturation.

But when I return to my temporary musical home base, it’s as if I’ve forgotten this frantic urge to dart around. I love to forget this! Suddenly, instead of needing to move in seventeen directions at once, I feel like I’m sitting still, stretching out.

For the past several months, my musical returns have all been movie scores, one after the next. The first was Fatima Al Qadiri’s score for Mati Diop’s Atlantics, an elegiac electronic drip with a rolling, propulsive structure. Returning to something this repetitive over and over, even while I’m skating on a shallow listen, allows the music to fuse into my experience. The movie score becomes a backdrop, a foundation. It becomes lived-in.

Movie scores have a supportive nature, which immediately negates the accusation that they’re just another thing. They’re not just adding to the big din; they exist to bolster something else. They’re proudly nonverbal, because words suck and are compromised—but even more so than other instrumental music, they stand out against an unintelligible cultural jangle, a crowded content space where more information is just more. There’s something grease-cutting about them.

The Atlantics score, for a while, was the only album that didn’t feel like work. Partly this was because it offered the general ease of any baseline album, which nullifies my knee-jerk habit to keep up. But part of this ease is specific to the nature of movie scores, which ferry some soft echo of narrative. When you return to them after watching the movie, they carry emotional weight as well as image cues. They come pre-textured. They tell me how to feel, but elliptically.

Movie scores carry the comfort of repetition itself: this has already happened. There’s nothing so chill, when you’re sitting down to do work, as hearing a note that captures the feeling of work already done. Scores are particularly satisfying to listen to over and over again because they multiply the effects of musical repetition, holding all the memory of the film they were born into. They’re slow and easily inhabitable. They let you stay past your welcome, to get more and more wrapped up in this blanket, to have a spot of your own to dip around in, whenever you want, wherever you are.

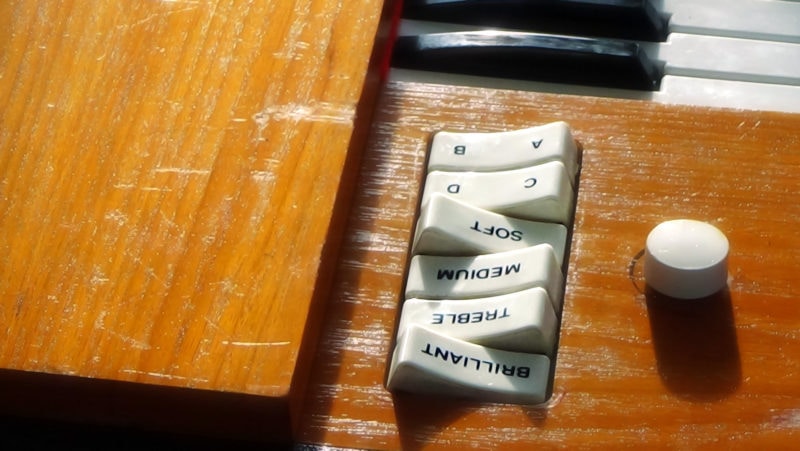

Atlantics, the movie behind the score, is about the tenuous position of labor, female autonomy, and torn love in Dakar, after a young woman’s lover is lost at sea. Al Qadiri pollinates her electronic symphonies with digital choirs, and her score is a propulsive current through this ghost story. The notes sound washed-out, at sea themselves, with an electronic Hohner Guitaret issuing big, mourning pangs.

The Atlantics score is mostly void of speech. You feel like you’re slipping through it, like rain through a tree. In an interview with Film Comment’s Sierra Pettengill, Al Qadiri says she wanted the waving synths to be on an aqueous churn: “Basically, I wanted it to feel like a washing machine, you know?” It’s the perfect combination for our precarious times: a wash and a push through the constant cycle.

After my time with Atlantics, I found myself listening to Emile Mosseri’s soft-hearted score for 2019’s The Last Black Man in San Francisco, which I’d seen some months earlier. In some ways, these two scores are diametrically opposed. Mosseri’s work is filled with swelling strings and warm, alive, un-ghostly voices. But they share an elliptical quality, maybe because they both accompany movies about very present losses—in the case of Last Black Man in San Francisco, a house and familial history departed.

Both movies are also about constant returning, ghostly lingering on something that has left. It’s a very “score-like” message: a score, while it traces narrative, is the shadow of narrative. This past week, my partner and I have been listening to Miles Davis’s (please don’t tease) score for a French movie I haven’t seen: Ascenseur pour l’échafaud. I would not be surprised if it was also about some haunting; that’s kinda what it sounds like—full of drums and trumpets circling each other, hovering like they’ve got some sexy bad blood and they’ll never forget it.

Because I’ve been listening to movie scores more, I’ve gotten into a habit of returning, into a habit of sticking around. Listening to a movie’s score after you’ve seen the movie is like running on a track around a game field well after the game has been played. It’s returning to the field and lingering, days later.

A few months ago, I discovered a clarifying explanation in Jenn Shapland’s new book, My Autobiography of Carson McCullers, when Shapland cites McCullers’s yearbook quotation (can you imagine McCullers being forced into compulsory pith?). Next to the black-and-white photograph is a snippet of Shelley: “Music, when soft voices die, vibrates in the memory.” This is antithetical to our world of cultural over-abundance—the imperative to constantly consume, to move on quickly, doesn’t leave much space for memory vibration. It’s hardly ever silent enough; we’ve got to pursue it now.

In an interview with Mind the Gap’s Zoë Elton on composing for Atlantics, Fatima Al Qadiri brought up a Muslim expression, kitabak maktoob, which she defines as, “your book has already been written.” Movie scores also make things feel fated in an especially exaggerated way. Everything is preordained—you know what happens next, you know where this thing goes, you know where this thing ends, but for right now, you’re just hearing this exact moment. You’re always in the instant where fate is being sealed.