Miscellaneous Files is a series of virtual studio visits that uses writers’ digital artifacts to understand their practice. Conceived by Mary Wang, each interview provides an intimate look into the artistic process.

In her latest book Imperial Intimacies, Hazel Carby confronts—and upends—the question: “Where are you from?” It’s a question familiar to those of us cast outside of whiteness, including Carby, who grew up in London with a Black Jamaican father and white Welsh mother. In her book, Carby moves between the “I” of the present and the “girl” of the past, tracing the “entanglements” between her Jamaican and Welsh family and the wider history of Jamaican slavery and British imperialism. By exploring the relations between working class Welsh life and the Jamaican colony, Bristol’s industrial center and the transatlantic slave economy, and the racial transgressions in the intimacies between her own parents, Carby’s critical project illuminates the histories of the British empire that are embedded in the spaces of our everyday lives.

Professor emerita of American and African American Studies at Yale University, Carby is part of an intellectual genealogy (along with Paul Gilroy and her mentor, Stuart Hall) that has broadened African American Studies to explore questions of race, gender, and identity formation within the wider context of geopolitics, diaspora, and colonialism across the Caribbean. In Imperial Intimacies, Carby delicately balances the critical distance of the scholar with the profound subjectivity of the memoirist. Like all of Carby’s work, it also dismantles the ”fictions of racial logic” that enforce binaries such as white and Black, colonial subject and citizen. It is these fictions, she suggests, that establish the conditional terms of who gets to inherit more than the family name. I spoke to Carby from my apartment in Brooklyn, while she was at home in Connecticut. Talking to her about researching, writing, and unearthing ancestors across two islands in this moment of powerful uprisings gave me hope that our entangled present may finally reckon with our entangled pasts, rescuing history from its totalizing logic of whiteness.

1. “The language that Black and brown bodies somehow are contagious is never very far away.”

Sabrina Alli: I’ve had a lot of nervous energy since the pandemic started, and I don’t really know how to spend my days sometimes. How have you been spending your time?

Hazel Carby: Lately, I’ve been researching seventeenth and eighteenth-century torture by crushing. I want to think about those eight minutes and forty-six seconds in detail. I want to parse out those minutes and seconds, but also give a historical background about the United States and torture. But I’ve either not been able to concentrate at all, or I’ve had to concentrate really, really hard. It’s very difficult—there’s so much we don’t want to think about, even while protesting.

Alli: To be out in the streets protesting is an interesting rupture to the pandemic. We’re inside, social distancing, and suddenly we learn about George Floyd’s death. Every season I have protested police brutality, but this time it feels like more people care. But I see a bit of disingenuousness to it: My well-intentioned white friends think they’re brave for speaking out about white supremacy and compiling an anti-racist reader. Everyone wants to educate everybody about white supremacy, and it feels like such an inadequate response right now.

Carby: In the 70s, when I was a public high school English teacher in the East End of London, I was an anti-racist activist. I’ve been here before, with the riot squad on every single corner and the police being extraordinarily aggressive. The person who is now my partner came to visit me in London and came on one of the marches—this was someone who had been involved in a lot of anti-Vietnam activity in America—and he was stunned at the brutality of the British police. But this has been going on for a long, long time. I know people feel they want to do something. I was a bit disappointed that the department of African American Studies at Yale thought that I should put together a reading list.

I’m interested in how we move from a call for change to actually imagining what that change would look like. I don’t think it is unrelated to COVID-19. The Black and brown people who were keeping the transport system going in New York City said they felt less essential than sacrificial. The structural inequalities that have lasted for many years suddenly erupted in the press. It was as if they discovered them for the first time.

Alli: When this quarantine first started in March, I was really diligent and used the time to read. Then I got the call that my mother had COVID-19, and someone had to go home to take care of my father, who has dementia. Somehow, I knew this would happen. It goes back to my family being the only brown family in this small white town in Michigan: We always seemed to be infected because of our difference and our closer proximity to illness, real or imagined. I’m thinking about how ingrained it is that I don’t get to feel safe. I went home and felt so ashamed. Mainstream media recognizes that, because of certain disparities, it’s mostly poor people of color who will suffer, but there’s a way in which we talk about Black and brown people as vectors for disease. I want to have a different discourse, but we always are the ones to suffer.

Carby: The language that Black and brown bodies somehow are contagious is never very far away. It was very explicit in the history of British colonialism. In schools in Britain, the history of migration after WWII was taught in terms of how Black bodies actually brought racism with them, as if it was a virus that infected the pure British body politic. These things take slightly different forms at different historical moments. But, yes, now when people want to blame Black and brown bodies for their own dying at a disproportionate rate, they say it’s because of their behavior.

2. “Even if you were extremely poor, imperialism could still make you feel that you belonged in a way that those in the colonies, who were your ‘subjects,’ could never belong.”

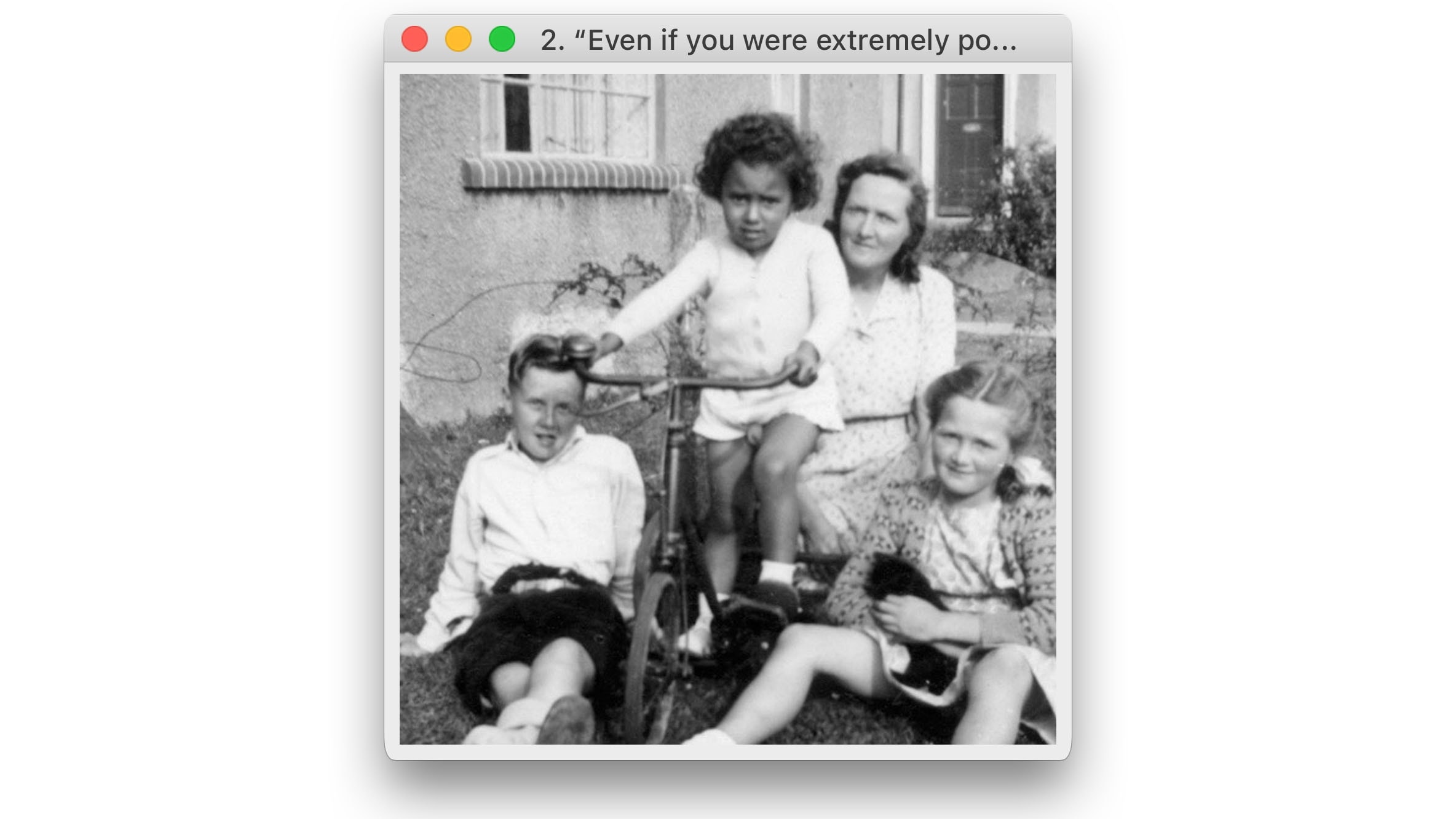

Alli: Can you tell me more about this photograph?

Carby: It was taken in South Wales, with relatives I used to stay with for the summer when my parents were working. On the one hand it was a loving relationship—they were caring for me—but on the other hand those cousins were always trying to wash the stuff off my skin. This is how I started to pick up on the language of racialized distinction. They lived forty minutes outside of Cardiff, and I started to realize Cardiff has had a Black population for 300 years. On our outings to the seaside, the brown bodies on the beaches were called pickaninnies. I was being inscripted into this racial thinking and the limits or the conditionality of how various relations of family were being thought of, how belonging was being thought of, and to what extent did you really belong.

I’m also very interested in the denial that the Lincolnshire family of Lily Carby [the slave owner ancestor of Carbyn who appears in Imperial Intimacies] was a part of. Many British families never acknowledged that they had family in Jamaica and that these enslaved people or their children were family. The familial term has never been applied to that imperial entanglement, that colonial entanglement. The only time you get a familial sense of belonging is when you’re talking about white settler colonialism in the parts of the Commonwealth that are Australia, Canada, or South Africa. There’s a sense that they somehow belonged to Britain in a way that, for example, the West Indies or India never did. Those populations were never addressed with the same familial terms. Rape was a form of control, which meant that they were family, but not recognized as such.

The conditions that dictate who belongs on what street are also interesting. On the New Jersey and the southern Connecticut shore, under social distancing, wealthy people who have houses are exercising all sorts of control to make sure that the shores are closed off to the “public.” These are battles that were rehearsed in the 60s and 70s, when wealthy white communities did not want Black and brown bodies on their beaches or in their waters. These are longstanding battles over space, proximity, and adjacency. You can be adjacent because you are washing the floor in the hospital, but you can’t be in any sort of proximity on the beach and in front of an extraordinarily wealthy person’s house. Though, you can clean it…maybe.

Alli: You write about your father recognizing Great Britain as his home. How can we belong to a nation that doesn’t want us?

Carby: It’s a double-sided question. One of the things I didn’t say in the book about those Welsh relatives or that whole maternal family is that it’s important to understand their racialization in the metropole, and how it cut across questions of class and poverty. Even if you were extremely poor, imperialism could still make you feel that you belonged in a way that those in the colonies, who were your “subjects,” could never belong.

I had to look at my Welsh relatives as historical characters. I wanted to understand how they became racialized and were conscripted into an imperial belonging as individuals in a way that wasn’t all that different from what was happening to colonial subjects in Jamaica. This sense of being conscripted into patriotism and national loyalties to the crown worked in very similar ways. I wanted to interrupt the narrative that when Black troops ended up in Britain during the war, or migrated after the war, they were somehow strangers. In fact, they were being educated in incredibly similar ways as white British people. In the book, I used the example of Empire Day, when there would be all these children in Jamaica waving their flags in their smart school uniforms, just like my mother was doing [in Great Britain]. Those who were colonially educated were in many ways world citizens, and when they landed into the metropole, they actually landed among an incredibly parochial, narrow-minded population who had no idea about what was going on in the world. The generation of my father knew everything about Great Britain, but perhaps very little about their own country. They were completely stunned to find that those they landed among knew nothing about Great Britain.

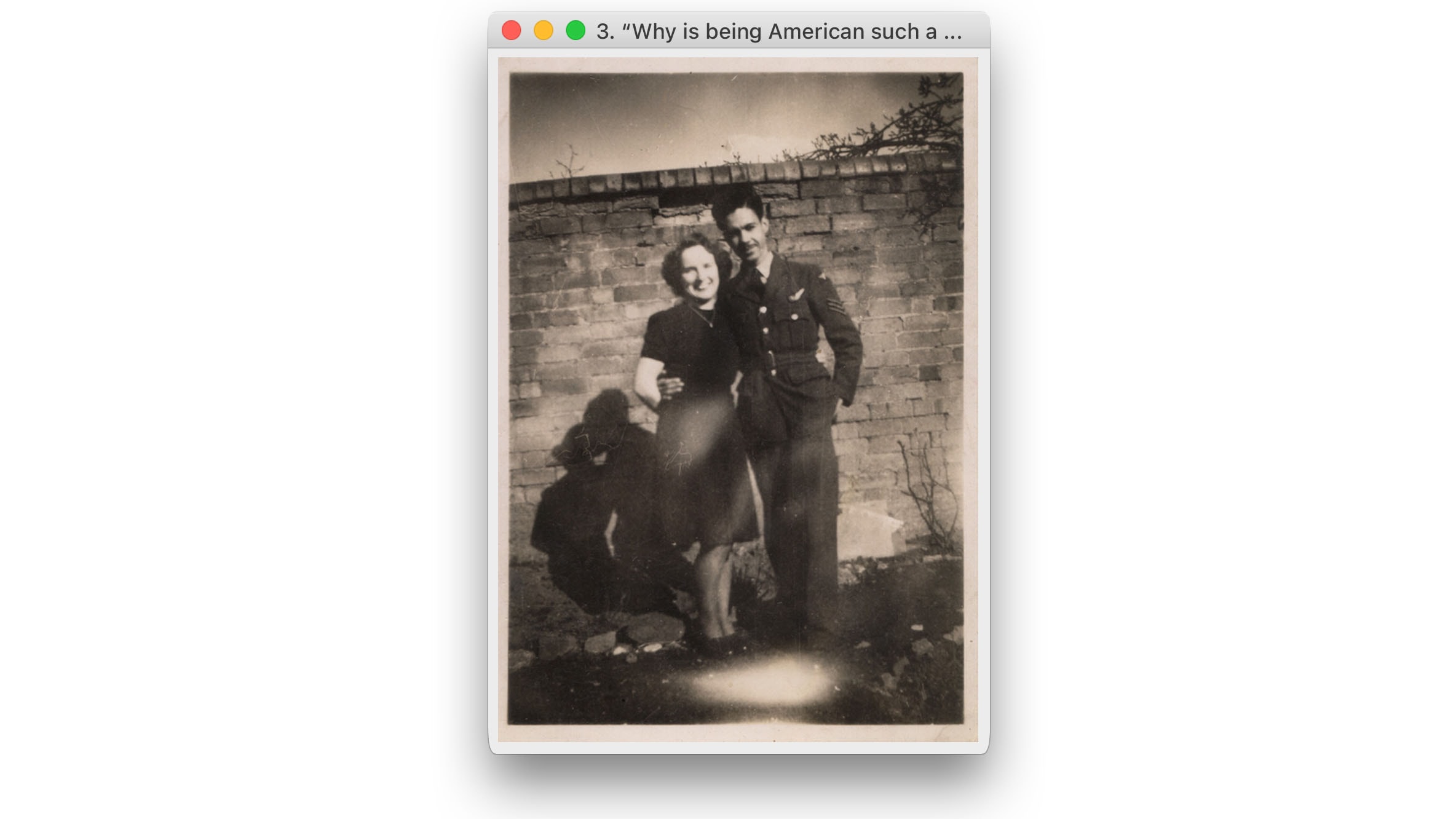

3. “Why is being American such an important part of that hyphen?”

Alli: I’m amazed at how generously you write about your mother, knowing that she refused to speak about certain things with you. My mother too is white and my father is brown. My mother has a steel wall around her about race. What was it like for you to write about your mother?

Carby: It was really difficult. The character of “the girl” [young Hazel] was a mechanism that enabled me to create a critical distance and make sense of what the child does not necessarily understand at the time and what it is the adult who’s writing knows—the adult who is also an academic and has thought a lot about the questions of race—without imposing that framework back on this figure of the mother.

I was also trying to understand my mother as a character and the role family secrets play. On the one hand, it was a question of exercising the recovery of memory, but on the other hand it was also about trying to take those shards of memories, sometimes very painful memories, and make sense of them historically. When you are a child, a parent seems fully formed. They’re just there, right? But I had to disrupt that process and try to understand them as historical characters produced in particular locations under particular historical circumstances, and try to use that as a critical framework to make sense of what the daughter was being told, what she remembered, what she didn’t understand at the time. At the same time, my mother was suffering more and more from Parkinson’s. She became an increasingly difficult person, and the resentments she had built up over her life became hardened. The Parkinson’s was reproducing stories I’d heard as a child, but I was now able to make critical sense of them. It was a complex, complicated process, and it hurt.

One of the difficulties I found about living in the US is how nationalistic the study of African American culture has been. What is that sense of belonging about? Why is being American such an important part of that hyphen? When I first came to the US, people would ask, “Why keep talking about the word diaspora?” There was a lot of resentment, because Black Americans were trying to make their way into the academy and the huge battles that had been fought in the street were then being fought in the university. They thought that this Black Briton, or worse, this West Indian, was taking a job an African American should have. So I had to listen very carefully to the way in which that resentment wasn’t necessarily directed at me as an individual, but at a wider struggle. Intellectually, the problem was that the history of African Americans was thought to be definitive of the entire Black diaspora, which it wasn’t. It’s always been important to me to show that what are thought to be Black bodies or brown bodies in different places are not exactly the same. For example, the history I tell of women of color in Jamaica is also about the larger questions of racial mixture, and what they have to do with class, and it’s different in the Caribbean than in the US and in Canada and in Germany.

Alli: I’ve always tried to find better ways to understand my race. I can’t be white and can’t be Black because the combination of my heritage doesn’t exist in people’s imagination. People didn’t understand that there could have been an Indian man, my grandfather, who migrates to the US to marry a mixed race woman in Ohio, my grandmother, who was a direct descendent of a slave. They had a child and that child married a white woman. In my family, there is a convergence around the auto industry, which for your family was the Great Western Railway. These forces of industrialization didn’t just bring people from the southern US to the north. People were coming from all over the world, but we still don’t have that narrative to understand how global the auto industry in the US was.

Carby: The only way to begin to come to terms with this sort of complexity is by thinking of race and ethnicity in a global framework. There’s no room in the framework of national narratives for these alternative narratives, and that’s one of the reasons I am so uncomfortable with this notion of anti-Blackness, because what does that exactly mean? If it can’t cope with the entanglement of all these histories—and indigenous histories—then, to me, it’s useless. Many people in the Caribbean will belong simultaneously to Trinidad and to Canada. Or to Jamaica and the UK. For me, nationalism is the problem. It’s the narrative that closes up precisely the story you outlined because that story cannot be contained within that national narrative. That’s a stumbling block not just for intellectual work, but a stumbling block for creating solidarities. In terms of the academy, it’s enough already with these very narrow units. How can it be that your narrative cannot be spoken, cannot be articulated within the frame of African American Studies?

Alli: The only home I’ve found in academia is in African American Studies. I was in gender studies and English departments, but it was really through the African American Studies departments that I felt like I was at least allowed the space for imagining an alternative sociality.

I’m grateful to the academic history that you are a part of, and this book is part of a tradition where academics are writing in the first person.

Carby: That’s because I have tenure, ha!

4. “Beneath the everyday soil, the everyday appearances, these entanglements of colonialism and imperialism are everywhere.”

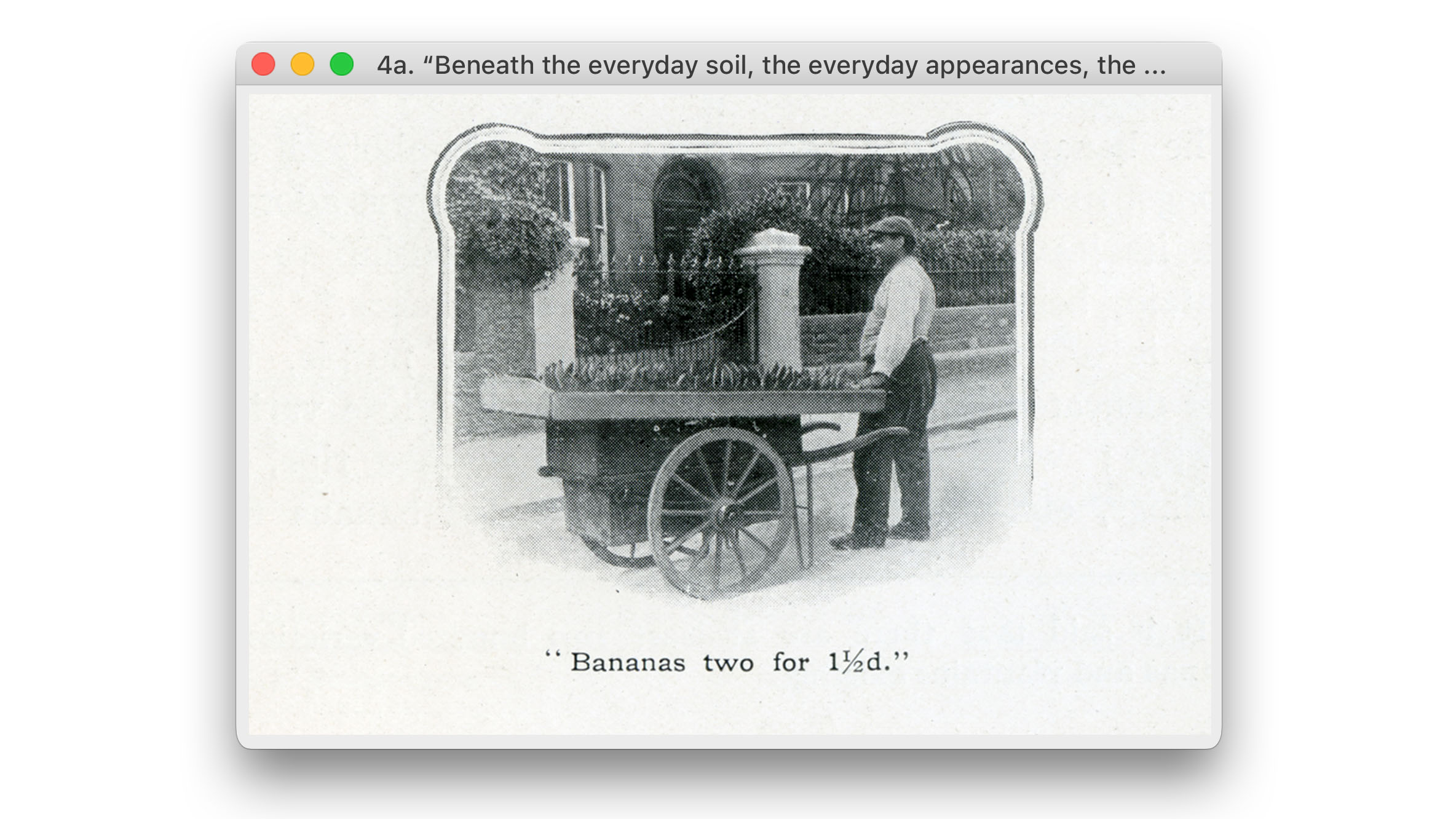

Alli: Can we talk about the photograph of a person selling bananas?

Carby: The story of Bristol was very important to my maternal family. But it was also important to me, because Bristol has this long history of involvement in the slave trade, so what my relatives appreciated in the civic culture and the opportunity in Bristol were because Bristol profited from the slave trade.

One of the issues I raise in the book is how the slave trade could be visible or invisible to the people who lived there. In terms of trying to imagine what my grandmother may have seen, it was very important to me to think about bananas, because that trade opened up when she was growing up. Joseph Chamberlain, who was Secretary of State for the Colonies, decided that Jamaican modernization was going to happen through bananas. The US was already getting involved in the banana trade, so the UK wanted to as well. It imported bananas on the one hand and modernized Jamaica by starting a tourist industry. I tried to imagine what my grandmother would have made of this banana seller who wasn’t in Jamaica, but was selling around the Bristol ports. Photographers were paid to take photos in Jamaica, to introduce it to the British. I try to imagine what it would have been like, with my grandmother sitting in one of the lantern slide shows that went all around Great Britain, how she could’ve been shaped by these encounters.

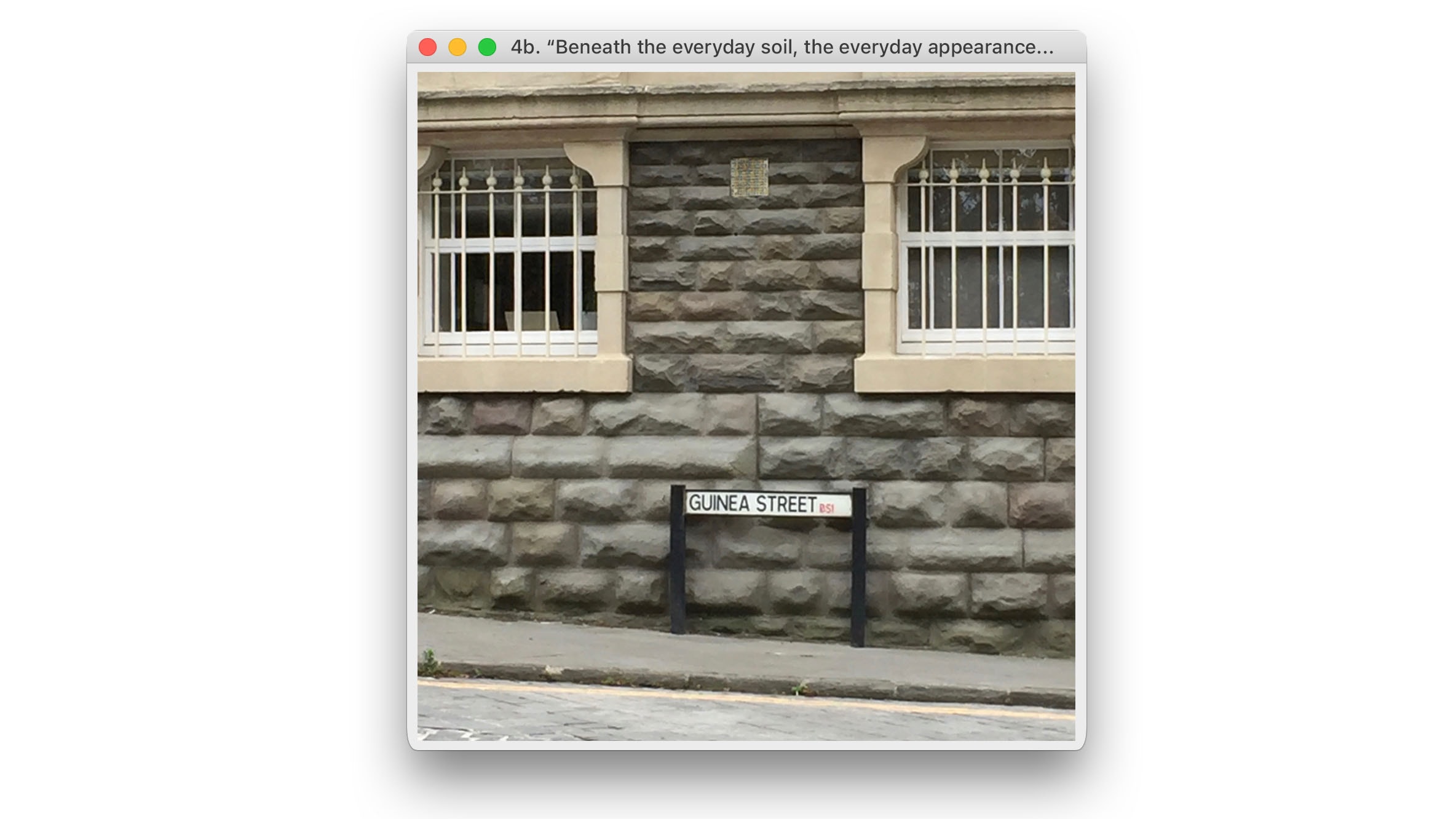

There’s also a photograph of a street sign, Guinea Street. How many people have walked down that street and seen that sign but not thought about what the origin of that term meant? Its origin comes from the artifact of currency, the guinea, which has its roots in the slave trade, but can you see that at a daily level? You’re left with this artifact devoid of history, and I want to return that sense of history. Bristol is a wonderful, incredibly rich place to do that in. Writing the book was ten years of research. I couldn’t tell the story of every city in Britain or of every single village, but the ones I chose were related to my family. One of the problems in contemporary Britain is that people imagine that the slave trade is a history only meaningful to aristocratic history—the big country houses built from its profits. But beneath the everyday soil, the everyday appearances, these entanglements of colonialism and imperialism are everywhere. Lily Carby was from a tiny English village. He was a British soldier. This is an ordinary story: It’s not about sugar barons, it’s not about the extremely wealthy. It’s about how ordinary people profited and had family in these colonies and profited from them, whether they recognized it or not.

Alli: You mention in your preface you’re writing to an ideal reader. Who is that?

Carby: I’ve worked on the book for so long and have been to many different places, and I realize there are very different readerships, particularly on either side of the Atlantic. In terms of conferences and gatherings, which attract more conventional historians, there was such deep wariness and resentment around thinking about race. “Not again,” I heard one historian say.

Alli: When do we stop thinking about race?

Carby: I had one British historian lecture me about how the concept of race was completely inappropriate to British history. He thought I needed to understand that the British were just very wary of strangers. There have been so many major books published recently that are apologies for empire, and they’re getting tons of attention—Niall Ferguson’s Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power, for example. Ferguson is an example of a historian who wants to recover the fact that empire did wonderful things all over the world. There’s this moment in Empire where Ferguson talks about being a child of empire, about growing up in Kenya and remembering that he would fall asleep to the sound of Kekeli women singing. It’s disgusting stuff, with a sense of absolute entitlement.

Academic readerships are often content to talk about how the notion of Britishness was formed in the eighteenth century, just thinking about the Welsh, the Scots, and the English, but taking absolutely no account of all the Black intellectuals who were writing then. These contemporary histories don’t feel like they have to talk about [Olaudah] Equiano, Ignatius Sancho, or any of the people holding together a multiplicity of possible meanings of Britishness that included Africanness.

But there are other audiences. I gave a lecture at Bristol and the people who put the talk together advertised it on local Black radio. I found a younger generation bringing the older generation in from the street, and not necessarily their relatives. To them, I was speaking a history that they longed to hear. They knew it. They lived it, but it had never been written and published in that sort of way. In the US, I found that people wanted to understand my lectures as being about the history of Black/white romances in the style of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.

5.“You can’t separate the history of accounting from the question of enslavement.”

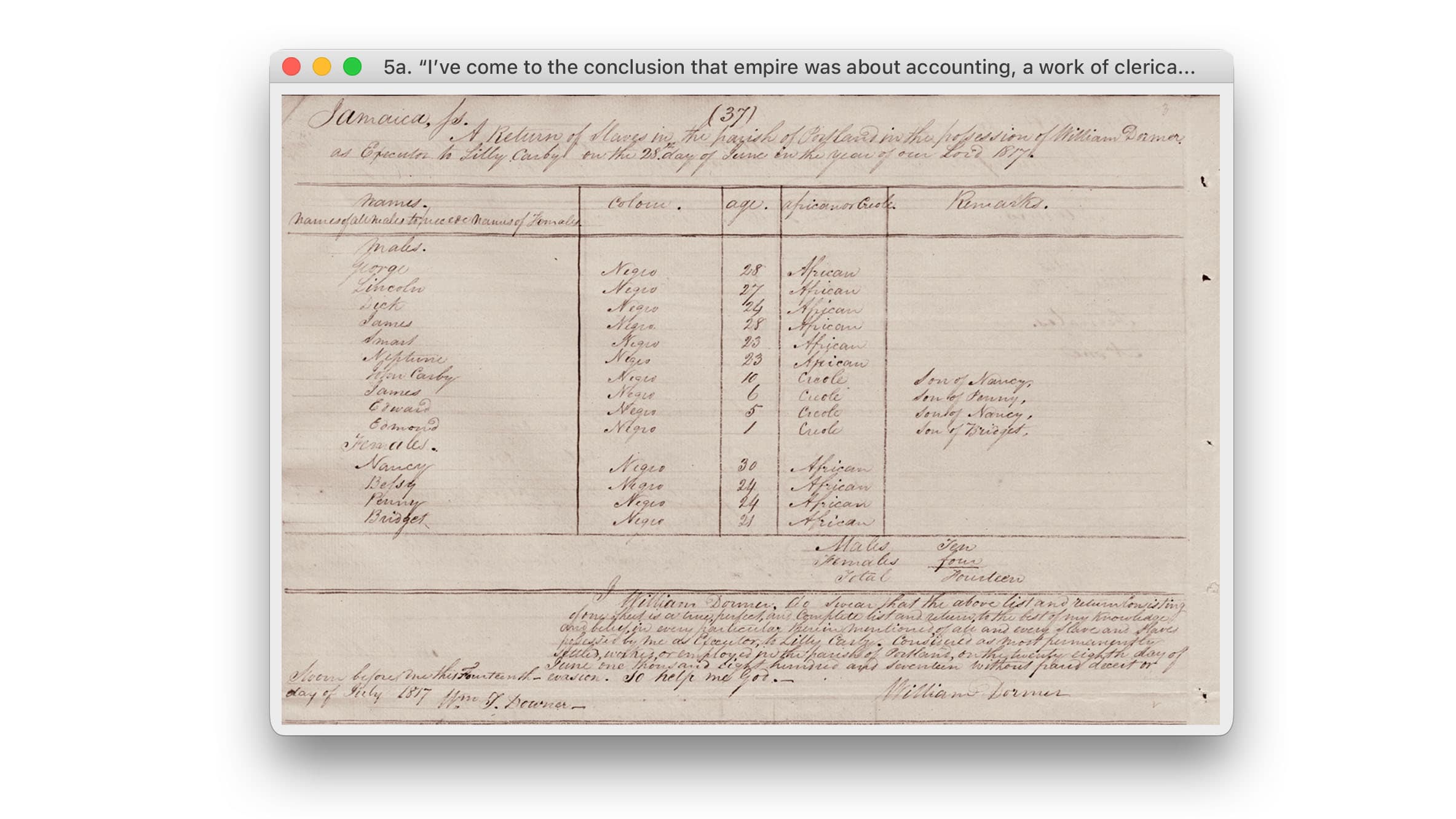

Alli: There are some photographs of documents from the archive. There’s a ledger of names.

Carby: That’s the slave register. That’s where Lily Carby is named as the owner of the plantation. I figured out who the other people were who signed it. You know, the clerks. I went to the Jamaica archives to make sense of it.That is where I found Lily Carby’s will. This was a product of scrupulous, painstaking archival work. It was a very unequal story too, because there were so many records in Britain about my maternal family. It was much more difficult trying to access records in the Caribbean.

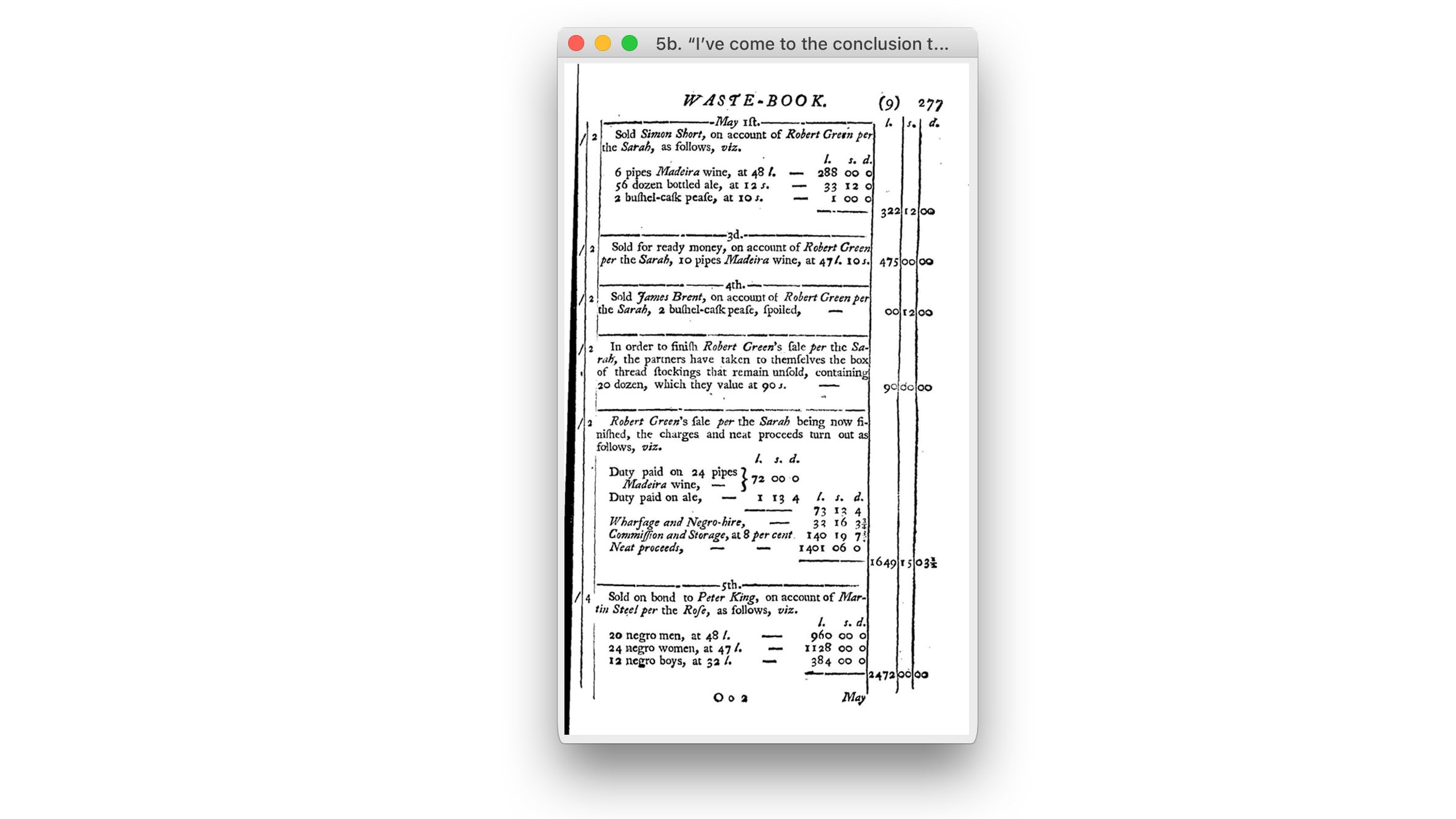

Alli: There’s also a document with the title “Waste Book.”

Carby: I’ve come to the conclusion that empire was about accounting, a work of clerical bookkeeping, in many ways. Double entry bookkeeping is actually an Arabic invention which was then imported to Italy and England. This [document] is a handbook for how to keep your accounts. In this teaching manual, “negroes” are listed alongside barrels of whatever goods. I spent a lot of time thinking about what that means. You can’t separate the history of accounting from the question of enslavement. I don’t think that accounting courses in schools of business are going to adapt this argument any time soon.

Alli: It’s very absurd, the performance of it. Even the handwriting. You write a lot about penmanship.

Carby: There were many things that I could never learn from the records themselves, so I had to think about it the other way: If it can’t tell me anything about where these Africans were coming from that were listed, what can it tell me about British character? I was taught in school that much of your character could be revealed through penmanship. If this is British penmanship, what does it say about British character?

6. “They had a sense of belonging even if they were rejected.”

Alli: I always forget how great Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song” is.

Carby: It was so important to me growing up. My generation was looking for different sources of affirmation than my parents’ generation. For my father, it was still important to him whether you were Jamaican, Trinidadian, or Barbadian. A lot of these ideas scripted who he thought I could go out with. But it was unclear to me that his generation really understood how to relate to my generation. We were born in Great Britain and the question about being Jamaican or Trinidadian, even West Indian, was totally irrelevant. Bob Marley, apart from being an incredible musical influence, articulated this very important process and urgency of needing to clear your mind of colonialism and imperialism.

The Lord Kitchener comes from my father’s generation of the Jamaican migrants coming to Great Britain. As I was saying at the beginning, they knew London, they knew Britain. They were bringing this knowledge with them and they came to rebuild Britain after the war. Britain was in terrible condition, and they built the national health service, they built the public transport service. They had a sense of belonging even if they were rejected.