Miscellaneous Files is a series of virtual studio visits that uses writers’ digital artifacts to understand their practice. Conceived by Mary Wang, each interview provides an intimate look into the artistic process.

In a way, every family story is a ghost story. Memories become tales, and tales—when repeated over and over—can become legends, and the lost figures who star in them take on a mythic quality. Novels about family sagas can help us plumb the depths of our own histories even further, nudging us to consider the past’s tentacle-like grasp on our present and future.

Maisy Card did just that in the writing and research for her debut novel, These Ghosts Are Family, born out of her receding closeness and connection to her family in Jamaica. Wanting to investigate her own history as well as her home country’s culture, Card began sketching a series of stories following characters she had encountered there or hoped to see brought to life. The end result is a novel-in-stories that follows the ancestors, descendants, and relations of a fictional Jamaican man named Abel Paisley. In Card’s telling, in the 1970s Paisley faked his own death, abandoning his wife and daughter for a new wife in England and then a life in New York. A family tree laid out in the novel’s opening pages offers a glimpse of the narrators who follow, each of their tales entangled in the family drama, revealing how the actions of one man can have a butterfly effect in lives beyond his own—including those of his children in New York and Jamaica, deceased wives, and a generations-removed female relative descended from a slave owner. The book is an expansive portrait of history, family, and the inextricable ways the two shape perceptions of who we really are.

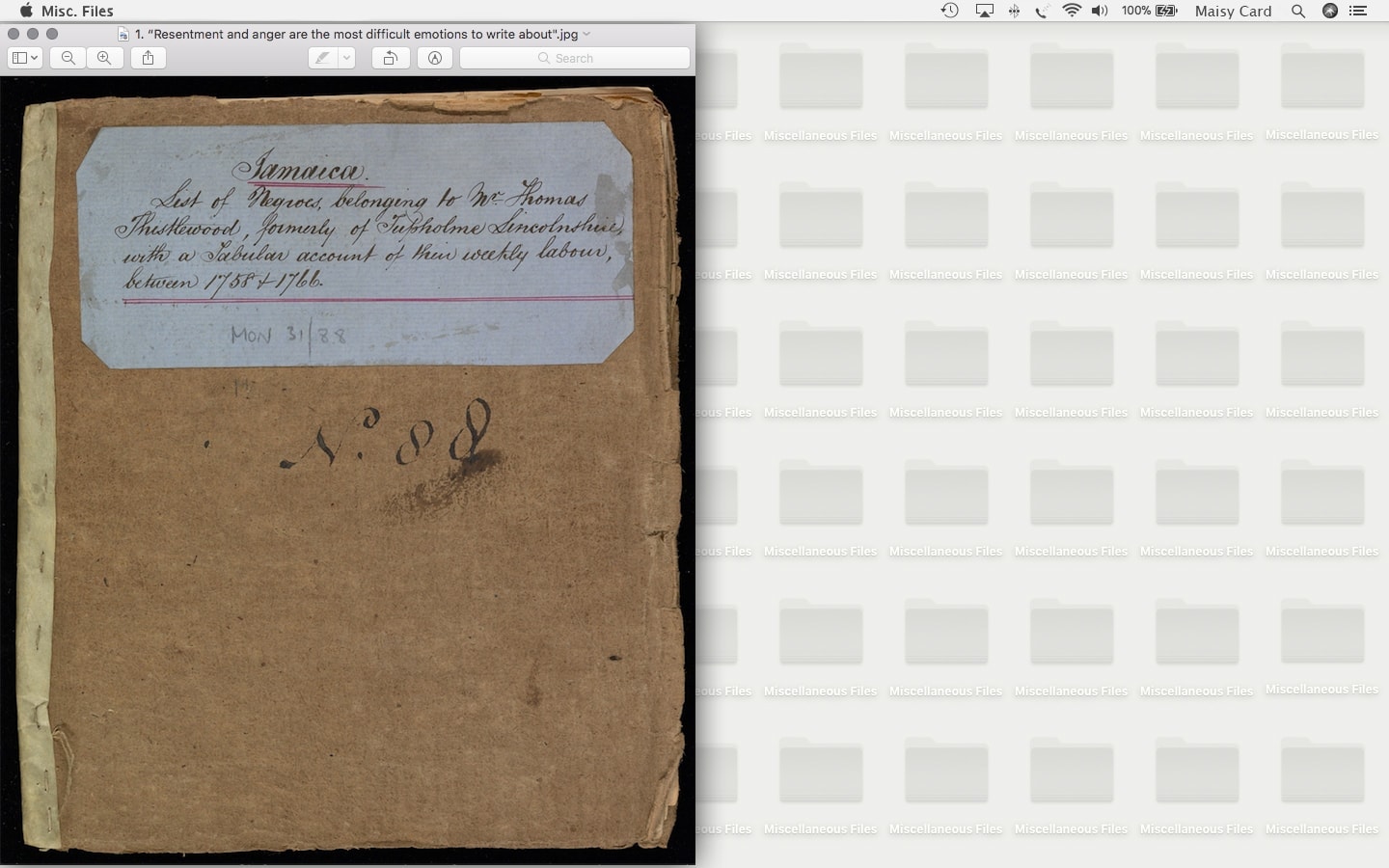

Card used her own grandfather as the basis for Abel Paisley. He was the reason she and her family immigrated to America—Card was born in Jamaica and moved to New York when she was five years old—but as he aged, she began to see a darker side of him, and to think more deeply about his complicated relationship with her family. Slavery and its impact are a primary subject too; These Ghosts Are Family stares down the history of colonialism in Jamaica and its continued legacy of colorism in stark, heartfelt prose. The novel took Card 12 years to write. Her background as a trained research assistant and credentialed librarian helped her undertake extensive research, which included uncovering her family tree dating back to 1834, when slavery was abolished on the island. A known diary of former Jamaican slave owner Thomas Thistlewood also provided (painful) inspiration. When Card and I spoke on the phone in February, just before her book’s release, we talked about her other influences—among them, works by Zadie Smith and Edwidge Danticat, and videos of “duppies,” or ghosts of Jamaican folklore.

1. “Resentment and anger are the most difficult emotions to write about.”

Mickie Meinhardt: Did you find using your family as a basis for the book painful, cathartic, or both?

Maisy Card: Both. On one hand, fiction is easier: I can imagine an emotional breakthrough (or breakdown) for each character, which doesn’t often happen in real life. On the other, I had to think about the emotions and experiences of myself and people in my family. That’s where the emotions got too real, perhaps. Resentment and anger are the most difficult emotions to write about. I can easily make a character’s anger my own, and I’ll find myself walking around with those feelings after working on the book, as if I forgot that I was writing about fictional people. But because the book took me such a long time to write, I was able to distance myself in the end.

Meinhardt: Howard Fowler, the slave owner character in the novel, was inspired by Thomas Thistlewood [an English slave owner in Jamaica] and his papers. What led you to them?

Card: I had read a couple of other novels set during the Baptist War, like Andrea Levy’s The Long Song and Marlon James’s The Book of Night Women. There’s a website called Jamaica Family Search that had some original testimonies from that time, and the Thomas Thistlewood papers came up there. Both Levy and James mentioned reading books about him and his diaries, too. So I continued my research and read Trevor Burnard’s Mastery, Tyranny, and Desire: Thomas Thistlewood and His Slaves in the Anglo-Jamaican World, in which Thistlewood’s diary is excerpted. There’s a section in which Burnard analyzes the diary to explain how slave women lived at that time, which was really illuminating. Even reading from the point of view of the slaveholder, you get a sense of the ways the women resisted.

One slave Burnard writes about is Coobah, who Thistlewood admitted to raping when she was 16. She ran away frequently, despite being violently punished every time she was caught. Thistlewood had her flogged and branded on the forehead, but she still defied him. At one point, assigned to work in the kitchen, she shat in a strainer. Thislewood had it smeared it all over her face and mouth as punishment, but she still wouldn’t submit. He eventually gave up and sold her to another plantation. Aside from the rebellions, I often read about slaves as passive victims. They were victims of course, but it was also comforting to know that, as brutalized as they were, many of them still found the strength to disobey. Many characters in the novel experience various kinds of trauma, but I wanted to show how their reactions were unique to their characters.

Meinhardt: Was the diary painful to read?

Card: Yes. Unlike some other slave owners, Thistlewood specifically wrote down every time he had sex with a slave. In his book, Burnard explained how Thistlewood had these codes [in the diary] for different acts. You want to think the stuff you read, like in James’s novel, is an exaggeration. But the original text is far worse than you could have imagined.

Meinhardt: In your novel, a white ancestor finds Howard Fowler’s diary. How did you decide on that?

Card: I was thinking about the idea of atonement. I wanted the novel to be about characters reacting to the same people and texts in different ways; I didn’t just want to write a character who was basically me doing this research and getting angry. I wanted to see how somebody who thinks they’re woke or educated would react to the knowledge that they’re not the victim, but the perpetrator. I kept thinking about the Henry Louis Gates/Ben Affleck scandal, where Affleck didn’t want to admit to the world that his family owned slaves. When we talk about reparations and atonement, admitting unpleasant realities is so important.

2. “The structure mirrors the way I learned about my family history, through stories told by relatives, filled with truth and untruths.”

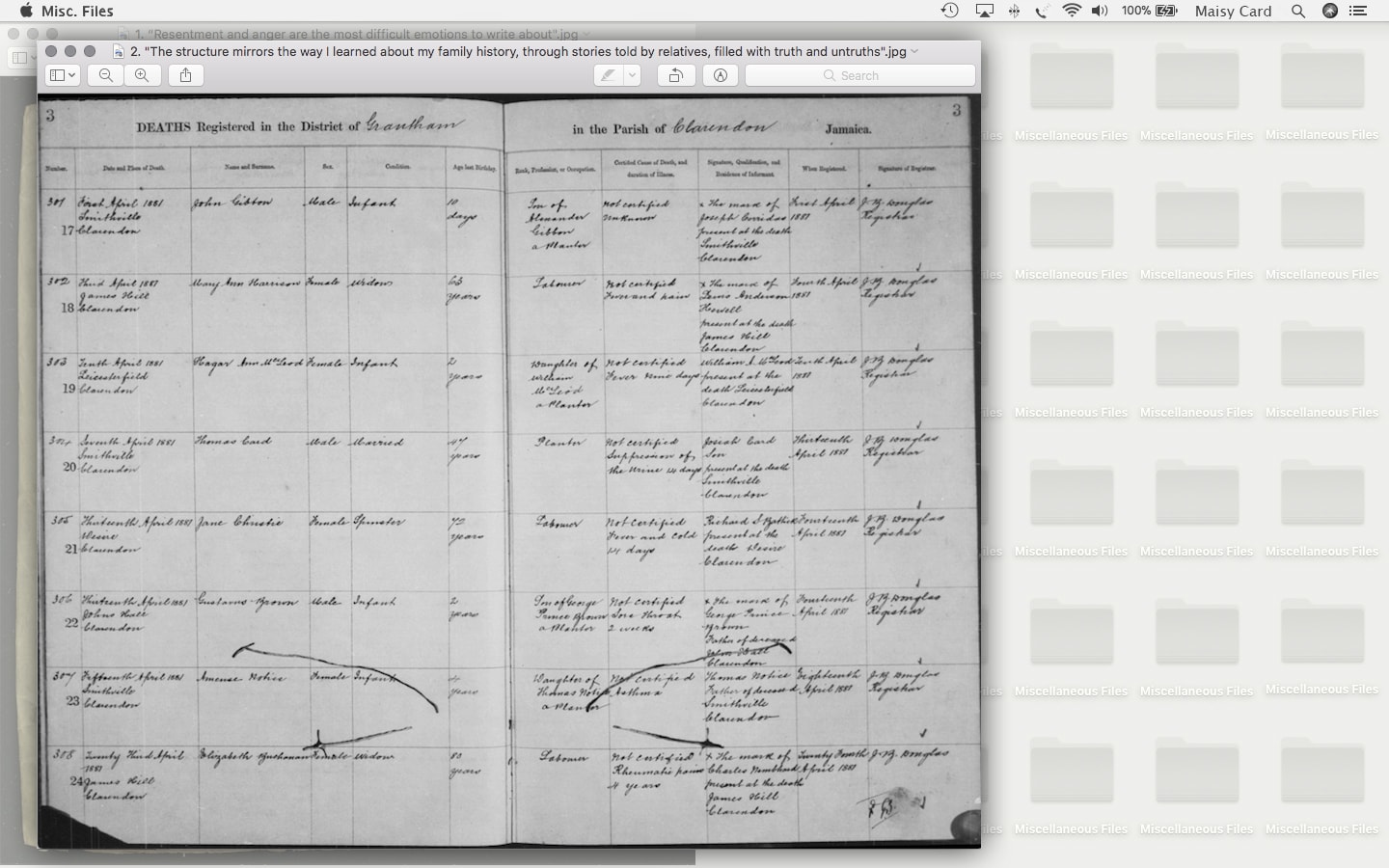

Meinhardt: I want to look at the log book. This is the oldest record you found of your ancestors, right? It’s a registry of deaths from 1881 in Clarendon, Jamaica.

Card: I did a DNA test on Ancestry.com, which shows you who your third or fourth, fifth, sixth cousins are, and I noticed that some of them were white and lived in England. I thought about how slavery could be our connection, and how they might react if they knew. The DNA test made me want to do more genealogical research. There’s another website, familysearch.org, which is actually run by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints—Mormons do a lot of genealogy, and a lot of genealogist training courses are in Utah. That site contains a lot of Jamaican birth and death records, all free, so I was able to find a lot.

It was very hard with my mother’s side of the family, probably because they moved around a lot and their last name, Golburn, is the same as many plantation owners. My father’s last name, Card, was a lot easier to trace because they’ve always lived around the same mountain area. For his side, I was able to go back to 1834, but because of slavery, that’s as far as I could go. It said that this ancestor—I think he was my great-great-grandfather, though you can never be sure—was born in 1834, which was the year the official slave system ended. There is this hazy quality to the past and to my family history that no amount of research can clarify. I had to accept that, and make sure those gaps in knowledge remain because they feel more true, even in fiction.

Meinhardt: You’ve cited Zadie Smith’s White Teeth and Edwidge Danticat’s The Dew Breaker as influences. White Teeth is a family saga; I imagine that helped inform your book.

Card: I read White Teeth in college, and it really resonated with me. There’s a moment when one of the characters, Irie, is at the house of the white family she befriends. She’s looking at their family tree and she realizes it goes all the way back to 1675. Irie’s mother, Clara, knows when her own mother was born, but the rest of their genealogical knowledge was “rumor, folktale, and myth.” In the book, Smith draws a family tree from Irie’s imagination with few concrete dates, and relatives whose names are unknown or are based on speculation—including an uncle who was rumored to have had 34 children by too many women to name. The issue of genealogical knowledge is presented for what it really is, something that mostly the privileged—those who aren’t descended from the colonized, the enslaved, or the poor—possess.

Structurally, I was inspired by The Dew Breaker, a book about a woman who finds out her father was a torturer for a dictator in Haiti. Every other chapter is from the point of view of someone he affected, either through torture or else. That was the first novel-in-stories book I’d ever read.

Meinhardt: Why was the novel-in-stories approach the best way to tell this story?

Card: The novel is a panoramic view of a fractured family, one that doesn’t know the truth about its recent history. The structure mirrors the way I learned about my family history, through stories told by relatives, filled with truth and untruths. Those stories that are just bits of a narrative that will never be complete.

I didn’t know my maternal grandmother. So what I know about her, I know from my mother’s memories, from stories other people told about my grandmother, or from stories my grandmother told my mother. Though my grandmother is dead, the person she was in my mind kept evolving based on the new stories I heard. I wanted the reader to share that experience. We get to know different versions of her, depending on whose story we’re experiencing. The challenge of this kind of structure is that it is incomplete by design, which I know that will frustrate some people.

3. “Writing the book definitely gave me the courage to ask more questions.”

Meinhardt: Tell me about this footage, which is from a visit by Haile Selassie [the former emperor of Ethiopia, who traveled to Jamaica in 1966].

Card: I was fascinated by Rastafarianism as a religion that came out of Jamaica. It represents the push and pull of the two sides of Jamaican culture: the colonial side that has ingrained anti-black mindsets, and the side that embraces everything African and is trying to decolonize.

Meinhardt: Is that dichotomy still very much alive?

Card: That was how I grew up. My father’s side, because they’re still based in the same area, were, after slavery, isolated in the mountains unless they worked in the city or migrated. Whereas my mother’s side is more coastal and urban, so there tends to be—I don’t want to say anything too negative—more colorism in that family. A little bit of that colonized mindset.

Meinhardt: Was that something you had words for growing up, or was it something you came to realize through research?

Card: My mother’s side of the family tended to be light-skinned. When I was younger, I was the only dark child. It didn’t look like I fit in, and that always affected my mindset. I heard these anti-black comments and had to accept [the family members making those comments] as they were. But at the same time, the mainstream interpretation of Jamaica is that we’re all Rastafarians, which of course isn’t true. Perhaps because of that, and because they were so positively black, there’s no sense of how they were persecuted. That affected me a lot growing up. That’s even the case with my name: Most of my family calls me Matara, a name given to me by a Rastafarian aunt. But my mother didn’t like it because it sounded too African, so my father had to change it to Maisy.

Meinhardt: Do you prefer one over the other?

Card: When I was younger I definitely didn’t feel connected to Maisy. Nobody in my family calls me that, so it was only used in school. But now I’m used to it. My legal name is actually Maisy-Ann but I dropped the Ann. Whenever I hear that, I cringe. It’s a British-sounding name, and I guess that’s where they got it from. It seemed like an appropriate name for a child, I suppose.

I’m used to being called Maisy now. Because I’ve ventured out and away from my family, it’s the only name I really hear. I only hear Matara or the other couple of names they have for me when I go see my family. It might be a sign that I’m not as close to my family as I was.

Meinhardt: It’s interesting that you say you’re no longer as close to your family as you used to be, since you just published a novel that evokes much of your family history. Was there any interplay between your relationship to your own family and your intimacy with the fictional family on the page?

Card: Writing the book definitely gave me the courage to ask more questions. I was doing genealogical research on my own family as I wrote, so I ended up quizzing my parents a lot. I had to get names, but I also wanted to see how far back their knowledge of our family went. I was writing about forgiveness in some sense, so I think over the course of working on this book, I also had to learn how to let go of some personal grudges.

4. “Jamaica is such a religious country, and ghosts are tied fluidly to religion.”

Meinhardt: Your book has the quality of a ghost story, and “ghost” is right there in the title. Were you investigating Jamaican myths, or did this have to do with something you encountered with your family? I was really interested in those sections that explore the power of abnormal or paranormal forces.

Card: I grew up hearing those stories. There are people in my family who say they have seen ghosts, but my mother flip-flops. She’ll tell a ghost story—just last week, she told me a story about how she heard a ghost when she was visiting my aunt—but then won’t say whether or not she truly believes it. It’s something that constantly came up when I was younger. My mother would say that the house she grew up in was haunted and that even though she didn’t see anything, other people did. Or she would talk about how she was in her mother’s room and something would knock the sewing machine over and the door would slam by itself. It’s a part of the culture but it’s also tied to religion, which I didn’t really think about at first. I thought of it as superstition.

But I was watching these videos, especially the one set in Rose Hall, trying to make sure I was correct in remembering that “duppies” [ghosts in Jamaican folklore] are perceived as being malignant. And I realized that Jamaica is such a religious country, and ghosts are tied fluidly to religion. Like if you can believe and if you use the power of God, you can exorcise these ghosts.