During college, I visited a friend who was teaching a summer session at a boarding school in leafy Western Massachusetts. The school had neo-classical buildings, a farm, and a principle of community contribution, which meant the children performed wholesome chores like milking cows or chopping wood on regular rotation. These tasks were called “workjobs.” I could not get enough of hearing people say this. Workjob. Workjob! In “workjob,” I could sense the prep school creaking towards an idea about labor, inadvertently tipping towards a philosophy about the roles we perform: abstracted, interchangeable, maybe even perfunctory. They almost got there—they almost made it—but they didn’t get the name quite right.

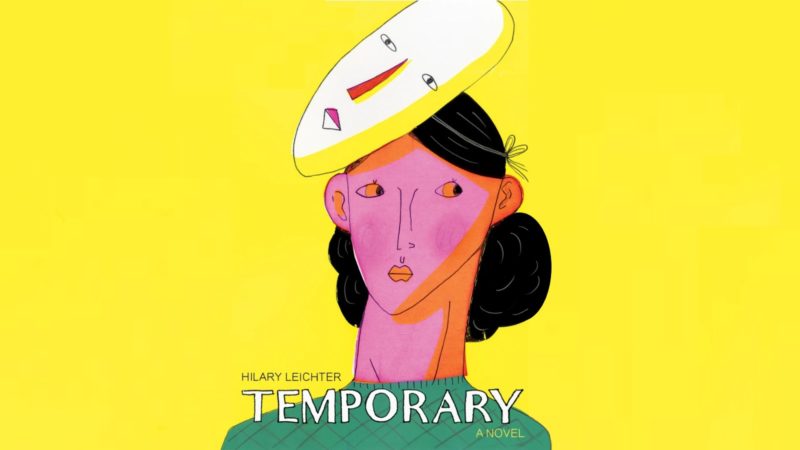

Temporary, a dizzying first novel from Hilary Leichter, presents a world so dogged by interchangeability that “workjob” kept floating in my mind. Temporary is a surreal extreme of gig economy slacker fiction. The protagonist, who is simply called “the Temporary,” is a type of work temp who never drops her temporary status, but careens from place to place eternally. Over the course of the book, our Temporary has twenty-three jobs, eighteen boyfriends, and no name. She, like all Temporaries, takes on the name of whoever had the job before her. The Temporaries occupy something like an underclass in Leichter’s world—which is similar to ours, but just to the side of it—a group whose success is predicated on their skills in the art of transience.

The book’s structure follows the Temporary on a run of job placements—each one stranger, more dangerous, more hallucinatory, and farther-flung than the last. Her world is marked by choppy brevity. As she says, “I have a shorthand kind of career. Short tasks, short stays, short skirts… My boyfriends call these positions A Great Opportunity, but they’re company men. They carry comedic mugs to their offices.” In our world and hers, we know not to trust someone who carries ready-made humor to the job.

For a second, you might be lulled into thinking that there’s freedom in the disruption—anything could be anything!—before you’re desperate for sense. The case Leichter makes here is not for freewheeling flexibility or a fantastic Nabokovian labyrinth, but for investigating the uneven foundation on which we already skitter around. At one point, when a boss asks our Temporary to emulate the persona of the previous Temporary, Darla, she assures him, “I’m putting my best self forward.” The Temporary then considers: “I think of my available selves, coagulated and discrete, compromising themselves for one another.”

Leichter paints a bleak portrait of a spreadsheet-capitalist, productivity-centric, personhood-agnostic dystopia, one similar enough to ours that we can understand how it works. “Temporaries measure their pregnancies in hours, not weeks,” Leichter writes at one point, which reminds me of companies paying their employees to freeze their eggs—childbearing considered for its perceived effects on productivity.

But allegorical simplification keeps Leichter’s work quite light on its feet. Though there’s little joy in the book, there is absurdity. The Temporary’s gigs are sometimes rearranging shoes, sometimes supporting assassins. Murder means little in this world, but the achievement of accomplishing the task of murder carries all the weight—it has a quantifiable result, plus a permanence to it. “Murder,” she thinks with satisfaction, “is a task that lasts.”

What Leichter provides for her readers in terms of her social landscape is not a bracing shot of clarity, but a recognition of the mess. Temporary seeks not to understand how we got here, but to capture the wooziness that, it’s true, we can’t understand how we got here. It’s a field report on how it feels to be stuck inside intractable inequality, to never get your feet on sturdy ground, to live in a loop. By nature, temporary-ness should be passing, but in its accumulation of moments, the book considers: Can temporary be forever?

And I haven’t told you about the boyfriends yet! Extreme interchangeability is not limited to labor only. Even lovers take shifts. For the Temporary, each partner has a better epithet than the last: my earnest boyfriend, my tallest boyfriend, my mall rat boyfriend, my pacifist boyfriend, my frugal boyfriend. Her casual tone about the many seems radically normalizing. And what could be heteronormative rigidity is both acknowledged and efficiently side-stepped: the Temporary’s great-grandmother had girlfriends, presumably just as swappable.

Leichter’s novel is emotionally convincing not just because of its narrative, but because of the linguistic dislocation that proves its premise. Language flips like it’s about to fall off the edge of the world. In one scene, the Temporary’s grandmother urges the Temporary’s mother (also a Temporary in her time; the Temporaries go back generations) to “be careful or you’ll end up unemployed.” The heft of this unmentionable word is palpable after it’s spoken. The Temporary even notes: “My mother had never heard her say that word out loud before.” Leichter strategically shifts weight here, moves things out of the way in order to illuminate. “Parent company,” too, becomes a haunted phrase. These feel like holes punctured into our communication; they offer a precious glimpse into the clockwork, and the brief idea that you might understand how the whole thing works. But then you’re up in the air again.

Leichter follows in a lineage of writers—Lucy Corin, Donald Barthelme—who displace language, often by just one notch. In Yorgos Lanthimos’s 2009 film Dogtooth, siblings trapped in a physiologically-twisted hothouse change out their nouns (“zombies” instead of “flowers”). Temporary also recalls Anne Carson, in Short Talks, when she writes: “I fear we failed to understand what he was saying or his reasons. What if every time he said cities, he meant delusions, for example?” Each of these writers aims at a different target (personal madness or authoritarian madness, just to name two) but achieves it through verbal swaps. The state of linguistic temporary-ness allows for flight and lands us in a new location.

Ultimately, Leichter’s is a universe of entropy. She skips back in time to show us the gods creating animals, only to let them go extinct. These are the same gods, we come to understand, responsible for thinking up the Temporary, for dictating chaos. We’re steeped in a world characterized by shift, begging for something sturdy to grab hold of. And so, when the book takes its few moments to soften and show its narrator’s yearning for stability—“The thing I admire about the arthropods is the way they… cement their houses to sturdy spots for good”—it shakes loose something similar in ourselves and hits the hardest.