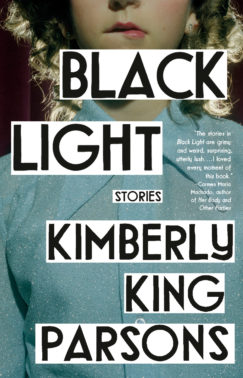

Kimberly King Parsons’ Black Light (Vintage) announces a singular new talent; it is bold and lyrical, cutting and comical. The voices in her story collection include queer teens experimenting with psychedelics, a man in a rage treatment program, young women suffering from anorexia, children compulsively catching insects—a slate of characters caught up in various games with drugs, sex, love, and deprivation. They are connected by a furious desire to flee the everyday.

Parsons’ stories revel in a kind of gallows humor. Heartbreak and dark comedy are inextricably linked. Take for example the story “Glow Hunter.” Sara, the narrator, is infatuated with her female friend Bo, a free spirit who “smells like weed and body lotion, some heavy-berry bullshit I’d normally hate.” Sarcasm is Sara’s shield, but it becomes very apparent that she is at Bo’s mercy, keeping not only the way Bo smells, but her birthmarks, scars, and odd turns of phrase “tucked into the hot folds of my brain.” Sara laments, “It’s cruel, really, what Bo can do to me.”

Humor becomes an antidote to dread, but sometimes only quiets the terror into an over-hanging anxiety. In “Starlite,” the final story in the collection, co-workers Jill and Rick skip work to snort drugs in a motel room all day. Jill revels in the seedy experience and their bad decisions. “It’s fun now,” she says, “but it’s gonna get so bad.”

Black Light was recently longlisted for the National Book Award, and Nathan Deuel at the Los Angeles Times says, “Parsons is an exhilarating, enchanting, charming, and irresistible new voice…Occasionally a debut collection lands with such a wet, happy thud that you immediately start imagining the rest of the writer’s long career.” Born and raised in Texas, Parsons is at work on a novel in Portland, Oregon, where she now lives.

I wanted to talk to Parsons about the humor in these stories, and the way her characters’ anxiety is reflected in her fractured narratives. We discussed her attraction to “hot, strange novels,” creativity, motherhood, and feeding her children lots of chicken nuggets so she could finish this book.

—Robert Lopez for Guernica

Guernica: Here we have the occasion of this excellent debut, Black Light, a collection of stories, and I know you’re working on a novel. So, the first question I have is how do you know what’s a story and what’s a novel? What might be similar about the two forms and how do they differ? And, do you prefer one or the other?

Kimberly King Parsons: The novel I’m working on now used to be a short story, though it never really wanted to be. Usually I’m circling and circling with every sentence, getting tight toward some feeling. But this story wouldn’t circle. And the narrator wouldn’t shut up. Because I knew it wasn’t right for Black Light, I’d set it aside, but I never really put it down. Then it was published (as a personal essay, which is hilarious) and I still didn’t put it down—a very rare thing for me. Usually when I’m done, I’m done. The document kind of festered on my desktop for months. I’d scroll down and add a line or a paragraph every few weeks at the end, but not in an artful way. Just the narrator being like, “Oh, and another thing…”

Later, when my publisher was talking with my agent about trying for a two-book deal, I pulled out that story and stared at it and knew it was a voice I could ride for a long time. I had ideas about where the narrative might go (most of which turned out to be wrong, by the way), and I wrote a synopsis and a little outline (also wrong!) and then I officially started calling my weird, swollen story a novel.

As a reader, I go for short stories first and short novels second. I respect compression above most things. I’m not saying a huge, baggy novel that spans generations and switches perspectives can’t be good—it’s just that those books aren’t usually about voice, and voice is what I want. My favorite novels are generally quick, hot, strange ones: Renata Adler’s Speedboat, Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights, Paula Fox’s Desperate Characters, Michael Ondaatje’s Coming Through Slaughter, Didion’s The Last Thing He Wanted.

Guernica: This is an excellent list of novels and Speedboat is one I return to again and again. I also respond to voice as a reader and we’re simpatico on doorstopper novels. The voice you’ve established here in these stories is taut, urgent, and poetic. How did you come to this voice? Was it an evolution or were you born with it, so to speak? You hint toward your method of composition on a sentence level, which certainly comes through in the work. The sentences are all meticulous and artful and deliver a gut punch when that’s what you’re after, but I’m wondering about the relationship between the voice and the sentence. Certainly the voice resides in the sentence, but is there more to it?

Parsons: I work line by line with each sentence being guided by the one that came before, (I suspect this is your method as well?) and with each story adhering to its own set of rules. Those rules always come organically, by “listening” to the thing I just wrote. I hope that doesn’t sound bonkers—it’s just that I know when each sentence feels “correct” and then I can move on to the next. This is how it goes for the first paragraph or two, when I’m figuring out who is talking and what they’re saying (or what they’re trying not to say), and who they’re talking to. Once I know who the players are, setting and circumstance comes through. But I definitely don’t sit down to write a story about kids catching spiders or whatever.

I intend for every story to have a different voice, or as different as they can possibly be when they’re all filtered through me. At the same time, some of my favorite writers sound very similar from one story or novel to the next, and I don’t mind this at all. Gary Lutz is incredible, and I don’t believe his goal is to embody a bunch of different voices. Lutz always sounds like Lutz, and that’s a beautiful thing. My friend Mark Doten is great at doing all sorts of voices; the writer Chris Dennis is a fucking ventriloquist. I don’t think I’m reaching all that far, at least not in my last two books, but hopefully my queer teenager from a shitty small town sounds a little different than my abusive, oblivious old guy from a shitty small town. That’s the goal anyway.

Guernica: The process you describe is the only one I’ve ever employed and all I could imagine doing. In almost all of the stories there’s darkness and light, people struggling with desire and need and rejection, yet there is humor all over the place. The first story, “Guts” is a perfect example for this. Tim seems like a typical doctor douchebag, but the narrator, Sheila, is raw and funny. Her encounter with the bald woman in the bar is a great scene. I suppose my question is about dark humor. The work I think both of us respond to the most is funny on some level. For all the talk about Lutz’s sentences, for instance, his humor doesn’t seem to come up as often and I think he’s hilarious on the page. How does humor work for you in a story? I imagine it’s natural, that it comes out naturally, but are you on the lookout for it? Do you think light is a necessary component in worlds full of darkness?

Parsons: I’ve always gravitated toward funny people—people who pay attention and are quick, sharp, maybe a little bit mean, but mostly self-deprecating. Humor is where I go almost immediately when things get bad in real life, like how can I punch this up? Which of my friends can I call right now to help me reframe this terrible thing? And it works, it really does. That’s the natural part. But I was afraid to be playful in my fiction for a long time. When I was a younger writer, I worried that going for the joke or undercutting lyricism would somehow make the work less important. I held on to that for the first five years or so, the idea that I had to keep that part of my personality out. I think ultimately it’s just the old adage about it taking a long time to sound like yourself. Having Sam Lipsyte as a professor during my MFA helped too. He’s of course known for humor, but my favorite book of his is still his first one, Venus Drive, which is hilarious, but also full of some of the darkest stuff imaginable—suicidal junkie humor that (somehow!) manages to not be bleak. A lot of the characters I write about are screw-ups, people making bad decisions or else letting life drag them around, but almost all of them are self-aware. I think that requires a sort of droll detachment. It’s Sheila realizing she’s in love with a person who is terrible for her but sticking around anyway. Or it’s the coworkers doing drugs in a motel room, knowing from the second they start how bad things will get. Sometimes you can only laugh at your terrible choices, even while you’re making them.

Guernica: Formal questions are always the most interesting to me and I’m a big fan of fragments and fractures. “Glow Hunter” is told in fragments and “Foxes” is fragmented as it moves back and forth between the story the mom is telling to her daughter and her thoughts about so much else, including commentary on the story, while other stories are told in a more traditional fashion with paragraphs and normal breaks. Do you find the form for each individual story immediately? Do you experiment with form until the right one presents itself? What are your thoughts on form?

Parsons: I’m also a big fan of fragments, especially fragmented novels. I love how they give room for your mind to keep whirring in the white space. Plus, I loathe writers opening and closing scenes for me. I’d rather be dropped in late and taken out early and given silence instead of answers.

That said, sometimes I have to ask myself if I’m using fragments because they’re what the story requires or if I’m using fragments because I haven’t figured stuff out yet. I think sometimes you keep writing and the fragments start sending little tendrils out to each other. They connect and suddenly time and space and the arc of the thing changes. But other times there is a resistance, a kind of commanding separateness of each block of text. No matter how hard you try to push them together, they repel. So, no, I don’t always know if I’m working in fragments or a more traditional narrative immediately—in the same way that at the beginning I’m trying to feel my way into a voice, I’m also trying to feel my way into form. But I love that, all the not knowing.

Guernica: I’ve always thought a good epitaph for me would be, “He didn’t know”, so I’m with you on the not knowing. Now that you’re about to publish a collection of stories, what’s something you do know? About the writing of stories, about the assembling of a collection, about all the jive that goes into putting a book out into the world? What’s enjoyable, what’s a drag? What’s surprised you, either with individual stories as you wrote them or anything about this process?

Parsons: That’s a brilliant epitaph. My initial response to this question was: not much! But I don’t think that’s exactly true. I know a lot about this particular book—how to write it and talk about it and hopefully sell it—but that knowledge probably won’t extend to the novel that’s due soon, and any knowledge I gain from the novel probably won’t help me understand the next book I write. And that’s okay. It’s great, actually—every project is so singular you get to be stupid over and over. I like to be in the dark, curious and baffled and bewildered every time.

Nothing about this process has been a drag to me so far, I swear. I get to talk to writers I’ve long admired (like you!) about writing; I get to have a team in this process with me; I get to do the thing I’d be doing anyway but as my job. I’ve said yes to damn near everything and sometimes that means I’m doing well with writing stuff and dropping the ball with responsible human being stuff. I volunteered to chaperone a field trip at my kid’s school and forgot about it. I forgot my mother-in-law’s birthday. I’ve fed my family a thousand chicken nuggets this month. But I know the flurry leading up to publication is temporary, and every single person who loves me has seen me work at this for fifteen years, so they’re letting me slide.

Guernica: This is all great to hear and you deserve all the sliding. Last question, in several parts…We talked earlier about cultivating different voices for each narrator and I’m curious if one or two of the stories were harder to complete, if the voices were more difficult to realize? And finally, we know you’re finishing a novel, so that’s what’s next, but have you thought about what you might want to do after the novel? Rest? Crime? Other books?

Parsons: I’ll say that finding the voice in any story takes me a really long time, but once I’m in it, things come (somewhat) quickly—it might still take months, but that’s quick for me. “Foxes” was one that gave me a lot of trouble, not because of the narrator’s voice, but because of the daughter’s. For a long time, she wasn’t truly on the page. There were a few gruesome lines from her stories, but they were taken out of context, heavily filtered through the mother’s voice, and they had no real parallel to the actual traumatic events that were occurring in the daughter’s life (the dad being gone, the dogs being gone, the mom’s drinking). I knew something felt off with that story, so I left my life for a little bit and spent a few days in an Airbnb messing with it, tearing pages apart, spreading little scraps out on the floor. That’s when I realized I needed to show the daughter attempting to wrench the narrative back from her mother, in her own words.

As far as what’s next, I like your suggestions—I could use some rest, maybe some light crime—but I’ll probably get right into a new book. The novel has been the center of my creative life for so long, but I’m never not writing stories. I have three new ones, plus a few that didn’t make it into Black Light for geographical reasons. If I had to guess, right now I’d say another collection will come after the novel, but it’s too soon to say for sure. I think it’s important to keep a secret—a project removed from the marketplace that nobody knows about or is asking for, something just for you. One day, when you’re ready, you drag the side project into the light, and it becomes the project project. Then, and this is my favorite part, you have to come up with something brand new to hide.