Aya de Leon wasn’t always known as a novelist. She was an activist first, a teenaged organizer with the anti-nuclear movement in the 1980s. In the late ‘90s, her writing career took off as she toured independently as a spoken word artist and slam poet. That led to her appointment, in 2006, as director of June Jordan’s Poetry for the People program at UC Berkeley.

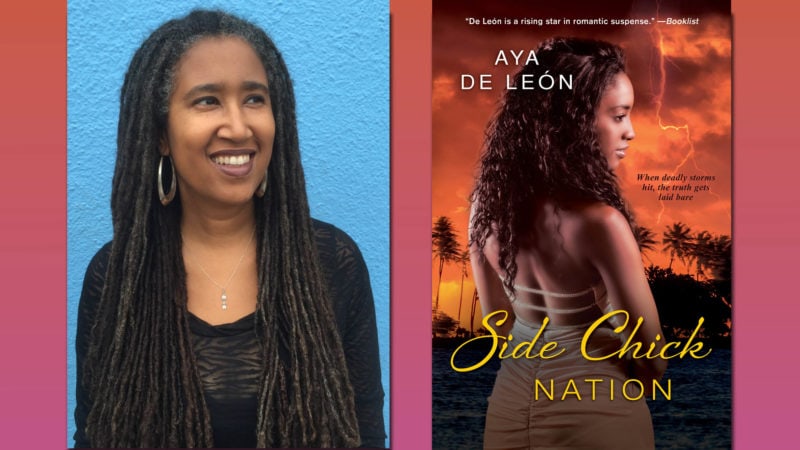

She’d been trying to write novels since early ‘90s, though, and it was through her fiction that I was first introduced to her. De Leon’s 2016 debut novel Uptown Thief is an adrenaline rush: It follows Marisol Rivera—a former sex worker, director of a public health clinic, and the madam of a high-end escort service—who adds another line to her resume when she and her employees become thieves, targeting a group of rich white men who traffic in young women. (It’s a plot that feels freshly relevant, with the surge of news about Jeffrey Epstein’s crimes.) Since then, de Leon has published three more books in her Justice Hustlers series: The Boss (2017), The Accidental Mistress (2018), and this past June, Side Chick Nation, one of the first fictional depictions of Puerto Rico during and after the devastation wrought by Hurricane Maria.

Side Chick Nation wasn’t supposed to exist; in 2017, when Hurricanes Irma and Maria hit Puerto Rico in quick succession, de Leon was working on a different fourth novel for her series. But as she watched the grim reality of Maria’s aftermath—and how it was compounded by the US government’s (lack of) response—she put aside that novel-in-progress and began writing through her grief and rage. It was personal as well as political: De Leon’s maternal grandmother was born and raised in Puerto Rico, married a US serviceman and immigrated to California with him, and was widowed shortly thereafter. She and De Leon’s mother (who was also a single mom) always felt a deep connection to the island, and the family’s link was kept alive in this matriarchal legacy. No stranger to the news cycle, nor to the long history of the island’s “lesser than” status as a US colony, de Leon wrote with urgency. She knew Puerto Rico’s plight wouldn’t remain in the news for long—and in Justice Hustlers she had built a world and a set of characters that could keep its troubles alive for her readers beyond short-lived Twitter headlines.

Writing in Jacobin in 2016, Jean Yang praised de Leon’s fiction for demonstrating that “activism is not only about questioning existing social hierarchies, but also about questioning existing ways of engaging in these discussions.” Indeed, many who notice Side Chick Nation’s gendered title and its cover, featuring a curly-haired model wearing a glittering, open-backed dress, might not expect to find in its pages a searing message of social justice, a rallying cry for equal rights, or what de Leon calls a “fiction of empathy”: one that centers women, people of color, LGBTQ folks, sex workers, poor and working 0class people, and immigrants. So many of us have been trained to believe that commercial fiction isn’t serious literature. But Side Chick Nation is serious. It is also a fantasy-fulfilling tale of sex workers saving the day by stealing money from the rich to give to the poor, having adventures full of good and bad sex, sugar daddies, fancy clothes, and celebrity.

When I met de Leon in person earlier this year, she excitedly told me about her newest book. “Last time, Dulce was saved,” she told me, referring to the protagonist of Side Chick Nation, who first appeared in Uptown Thief. “But this time, she saves herself.”

Ultimately, The Methodology of the Oppressed, by the anticolonial feminist theorist Chela Sandoval, was what gave me language to understand and discuss so much of what I admired about de Leon’s work: the way it moves between modes, doing the work of concientización (or consciousness raising) through clear ideological underpinnings of equality and justice, while also appealing to readers who are looking for an escapist romp that acknowledges the realities of our world without sugarcoating them. De Leon treats her characters as full human beings with complex thoughts, desires, and contradictions, living in a world as complicated as they are—and with the same potential for transformation.

—Ilana Masad for Guernica

Guernica: You’re a poet, fiction writer, activist, and teacher. How do those roles relate to one another?

Aya de Leon: In many ways the activist comes first. When I started writing fiction, I had ideas. I had a novel in my head. But I didn’t yet have the skills to do two things: create a character or set of characters that go on a journey, and create the sentences out of words to tell that story.

The work I’ve done to write and study poetry has really helped with the latter—creating the language to tell the story of a character’s experience and journey. Fiction writing has been a huge undertaking for me. All my fiction comes to me as action and dialogue: She throws the pad Thai against the wall and cusses him out. But there’s a lot more going on in that moment that’s in my imagination, that doesn’t get on the page. It’s taken me a long time to develop the skillset to put the activist message out in the world through character-driven fiction, and to enhance the reader’s experience with fresh language.

My poetry teaching has really pushed me here. In June Jordan’s Poetry for the People program, where I teach at UC Berkeley, I inherited a set of rules about how to write poetry. They forced me to learn how to show instead of tell, and I was able to translate that skill set into my fiction. Those guidelines were really hard for me to master, because my spoken word poetry was all “tell”—like a monologue—so I had to develop the capacity to create a world through language that could stand on its own. After years—decades, really—of working on that with my fiction, I finally feel like I can get the picture in my brain into a reader’s mind.

Guernica: The Justice Hustlers series draws on a few genres: romance, street lit, thriller. Were you a reader of these genres before you decided to write them yourself? Was there a particular audience you wanted to reach?

De Leon: I’ve been laughing lately as I look back at Uptown Thief, because I was literally trying to throw every genre at the reader that I could. I was determined to write a book that would appeal to the widest array of women readers possible. It’s street lit, it’s a thriller, it’s a heist, it’s a romance, it’s erotica—it’s got straight sex, gay sex, romantic sex, addictive sex. Tropes? I’ll give you all the tropes. It’s got fabulous shoes. It’s got women going shopping. It’s got women betraying each other and fighting over a man. But it’s also got girl power, where women band together and overcome that. It’s got a big deadly confrontation with the villain at the end. It’s got women being rescued, but they’re being rescued by other women. I try to flip the tropes.

I came up reading mostly mystery. I always loved a mystery with a good romance. I can watch a rom-com, but a romance book usually wasn’t the right balance for my tastes. I always loved spy books and heist books, but it was harder to find them written by women.

When I started the series, I loved the idea of writing heist because the politics are inherent: Who is stealing what from whom? And the perspective is often that the person with the money doesn’t deserve to have it, and that the heroes are stealing with good reason. That worked perfectly for what I had in mind with these women. More recently, I came across a few fabulous YA girl spy books, all with white teens. Now I’m working on a YA spy series with girls of color.

Guernica: Many writers believe that art can change the world, that fiction has power and importance in and of itself, as a pure kind of art form. At the same time, many writers and artists today feel their work can’t end with fiction, because while art matters, immensely, it doesn’t change the world on its own. Do you find yourself doubting the power of fiction as you write, or believing in it more?

De Leon: I also write non-fiction, because sometimes I need to just say something, as opposed to building a world and characters to live out a political reality. But one of the things my fiction does is give an interior to women of color from poor and working-class backgrounds, most of them current or former sex workers, some immigrants.

Whatever I think about stories, the reality is that people in all cultures consume them and they affect how we see the world. I’m moved to write stories about women who are usually written off, or who typically appear in service to other people who are more powerful. And I think that makes a difference. Our world lacks empathy, and fiction creates empathy. I’m creating a fiction of empathy toward women, POC, LGBTQ folks, poor and working-class people, folks targeted for incarceration, immigrants, and sex workers. I’m also creating fun and joy. I’m portraying people who don’t usually see themselves and their communities as heroic, even though they’re up against obstacles that require acts of heroism just to survive.

I guess I see these stories as being part of a larger conversation and movement. I don’t expect my novels to shoulder the burden of solving anything all by themselves. The things I am saying—women are people, sex work is work, Black Lives Matter, immigrants deserve human rights, people are poor due to structural inequalities, not bad personal choices—none of these is being said for the first time. My goal is to get these messages into fiction that has a mass appeal. I want women—particularly low-income young women of color—to be reading fiction that has these messages embedded in it, when they may not be getting them in other ways. Also, in this country, our literature is very segregated along class lines. I want to reach a really broad range of women readers, so that women from different class backgrounds can be part of the same conversation through fiction.

Activists often like commercial fiction, but have to ignore the sexism or racism or homophobia or classism to enjoy a fun, fast, sexy book. Now people don’t have to choose. And if people who don’t think of themselves as political pick up my books and gain any political insight while enjoying them, then all the better.

Guernica: In her profile of you in the Washington Post, Jessica Langlois quoted Audre Lorde’s famous statement—the master’s tools can never dismantle the master’s house—and then wrote, “but that’s what de León is trying to do.” I understood her to mean that your books use mass market appeal to package social justice messaging. Do you think Lorde is wrong? Or are there just many ways to dismantle the master’s house?

De Leon: I am not ready to concede that storytelling is the master’s tool. The commercial literary industry is definitely part of the corporate infrastructure, particularly with the consolidation of so many presses over the past few decades. In that way, I see these books as Trojan Horses. “Oh, I’m just hanging out here in the master’s house being sexy…” But meanwhile, my characters are stealing ill-gotten gains and forming stripper unions and challenging respectability politics and fighting colonization and climate change. The more the “master” expands his house, the more we need to have organization for resistance in every room.

Guernica: In the author’s note of your newest novel, Side Chick Nation, you wrote that you had to scrap the novel you were originally writing in order to write this one about Hurricane Maria and Puerto Rico. How did you emotionally approach that switch, and what was it like writing into that real-time tragedy?

De Leon: I just knew I had to write it. I wanted to talk about Puerto Rico on the biggest possible platform, and the biggest platform I had was the feminist heist series I was writing. So it was just the logical conclusion that I needed to pour my emotion and effort into this novel.

For several weeks, I was frozen. Eventually, I had to cry a lot to get past the feeling of being immobilized and defeated. I felt totally inadequate to tell the story. But I had this opportunity, and I knew that Puerto Rico would have faded from the headlines by the time the book came out, and I didn’t want that. There’s this typical challenge that children and grandchildren of immigrants have, the feeling of not being enough. I’ve always felt not Puerto Rican enough. But the demographic shifts in PR, combined with the hurricane, have changed the relationships between Puerto Ricans on the island and in the diaspora. We need to show up for each other. So I decided that I couldn’t stand on the sidelines wringing my hands. I needed to dive in, get help, and do my very best.

Guernica: How did you approach this novel in terms of craft?

De Leon: When I was writing the previous books in the series, I was anticipating what was coming in the next book, and introducing characters and situations and relationships so that everything would be set up for the next one. This time, I didn’t have any of that.

I needed to dig through my own past work to find the people and the situations that would give this book life. I found Dulce in Uptown Thief; she’s a tragic figure who had been rescued. I had to figure out how to un-rescue her and get her to Puerto Rico where—at that point—she had no roots. So I got her from Cuba [where she is at the end of Uptown Thief] to Miami, and into trouble. Then I had her running to Santo Domingo to get out of trouble. I was trying to figure out how she would get to Puerto Rico, and the idea of the sugar daddy came up. It was perfect, because he could also be the obstacle in the romance with a really great guy. So I had a triangle going, and that solved a lot of the romance.

Then I had to figure out how to get some heists going, and I recalled a short story I had written back in 2016 about the debt crisis in Puerto Rico. I figured out how to work it into the book, which introduced new characters. I realized they would be really important in the hurricane, because it wasn’t enough to just have Dulce, an outsider, be there as witness. I also needed women who had been on the island their whole lives, who were losing their home and everything they’d ever known.

Guernica: What was your research process like?

De Leon: I started online, reading everything about the hurricane I could. Then I went to local gatherings where people were talking about and reporting on the hurricane. I went to a conference in Chicago about the hurricane in the spring of 2018, and that really grounded me. I read Naomi Klein’s The Battle for Paradise, which grounded me a lot in the contemporary political situation. And then I went to Puerto Rico in June of 2018 for the first time in a decade. It was powerful to connect with my folks there, and painful, and eye-opening. I needed to be a witness, before I could write a witness character.

Guernica: There are some very powerful metaphors in this book: Dulce gets a gold Cartier chain from a sugar daddy early on, a chain that later literally hinders her. Another metaphor is the title, which evokes Puerto Rico’s status as a kind of “side chick,” treated like an afterthought of the US, a place to invest and play and live tax-free and then abandon when it starts getting old or dirty or unpleasant or dangerous.

De Leon: In 1999, I wrote a poem called “Grito de Vieques” which compared the US military’s treatment of Vieques to that of a sexually abusive stepfather. After the hurricane, I wrote the side chick poem that shows up in the book, because the sexually abusive metaphor didn’t work, but there was still the sense of gendered exploitation: I want you there for my gratification, but when you need me, I don’t owe you anything.

The Cartier chain came from my visit to Puerto Rico. I was looking around for a hotel that could be the setting for Dulce’s first sugar daddy arrangement. And there was the Condado Vanderbilt Hotel. It was eight months after the hurricane, and the hotel was cleaned up and back on its feet, but across the street was the wrecked and shuttered Cartier jewelers, and it just captured my imagination. I spent a long time on hold with Cartier to find someone who could confirm that the store was open right up until the hurricane. Chains hold things together, but they also restrain and constrain.

Guernica: Delia Borbón is your fictional celebrity, a former stripper and sex worker who works for incredible causes while also being glamorous and popular. Did you base her on any real celebrity? Is she aspirational, the kind you wish we’d see more of?

De Leon: I think many of us love Cardi B and Amber Rose because they own their histories. Delia Borbón isn’t really based on anyone, but I invented her as someone who could bridge the worlds between celebrity and sex work. A sort of female OG who could command huge audiences, but would donate her time to support a low-income women’s health clinic. A ride or die for the old hood. I keep finding ways to put her in each book, because I love her so much.

Guernica: In this novel, Dulce finds her voice through a burgeoning journalism career. Her path reminded me of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s recurring Hamilton lyric, “I wrote my way out.” Is Dulce writing her way out? How does her path to writing echo feelings you’ve had about your own writing?

De Leon: One of the things I’ve loved about writing Dulce in this book is getting to know her. And giving her an arc to move from a tragic figure that Marisol [the protagonist of Uptown Thief] could rescue, to a three-dimensional character who could grow and become a full subject. In Uptown Thief, I was playing with the sex work trope of rescue, but instead of affluent white US women rescuing sex workers who don’t want to be rescued, I had a sex worker rescuing a young woman who’d been pimped.

That seemed important for a couple of reasons. First of all, it showed this sex worker, Marisol, as a woman with agency helping another woman, Dulce, whose agency had been stolen. Sex worker activists are forever pushing back on narratives that paint everyone in the sex industries with the same brush, because the needs of those who do sex work by choice are different from those who do sex work for survival, which are different from those who are coerced or trafficked. And any one-size-fits-all approach to the sex industries will do as much if not more harm than good (see SESTA and FOSTA). But having this rescue also points out that sex workers are naturally part of the solution to trafficking.

Depending on your definition of trafficking, Dulce may or may not fit. But she’s definitely a survivor of sexual exploitation, abuse, coercion, and pimping. Jerry, her abusive pimp, intended to break her spirit so he could control and exploit her. And for a time, he did. But after Dulce is rescued, she moves slowly through the process of putting her life together. First, she has to do some emotional healing, getting through the PTSD that came up the moment she got out of the situation that had her in constant crisis and survival mode. She finds a new normal, but it’s one that still includes a lot of misconceptions about herself and her worth. So she turns to Zavier [a sweet journalist she’s gone on a couple dates with], to rescue her from post-hurricane Puerto Rico, but in the process she recalls her earlier love of writing. It was exciting to write her love of writing into her back story. It also really added to the sense of this young girl’s life being derailed by sexual violence.

That’s the thing about objectification: Every girl who is pimped was interested in something else before some guy groomed and exploited her. I loved the idea that Dulce could get enough support and healing that she could go back and reclaim some of the life she’d wanted before this abuser and exploiter made her world so small. So yes, Dulce is definitely writing her way out.