This was the plan before the good news became bad news: You would pack your bags and leave them in the car. You would drive down to Omaha after the ultrasound. You were traveling to visit friends, to see a total eclipse, though your real reason for going was to share the good news.

But then the heart stopped beating, like a light switched off. And when you cried together in the clinic parking lot, you asked one another what to do: stay home and grieve in bed, or go to Nebraska and be among friends? There was no right choice. You repeated this to one another like a promise.

You also promised, while in the car headed to Omaha, that when you arrived, you would tell your friends the truth. “Don’t hide your grief. Don’t pretend these things never happen,” you told each other. But when you walk into that warm house, where they offer you a drink, the bad news hardens and sinks inside of you and you cover it with a smile for the next three days. You gather on patios to drink and catch up, a music festival playing in the distance, the taste of alcohol twisting the knife. While one of you sits outside on the patio late at night faking it, the other is in the bathroom inserting hormone suppositories to trick the body into thinking it’s still pregnant, so you won’t miscarry on your friends’ wood floors.

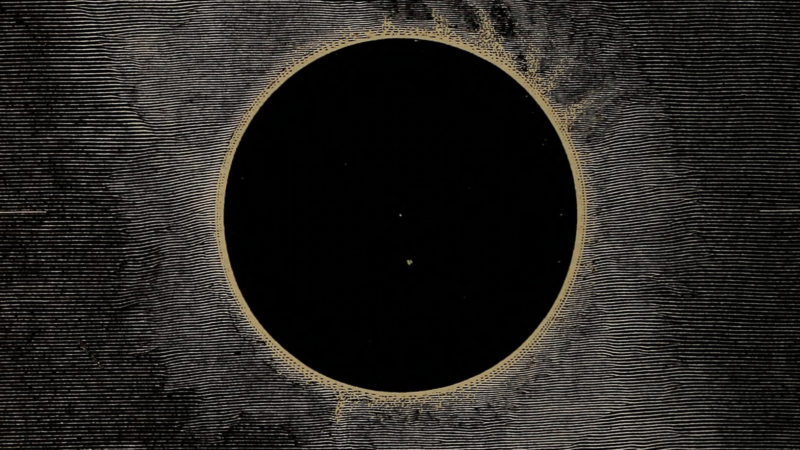

Most of the weekend ends up a blur, but you will remember the eclipse: how you stood in the ditch along a country highway outside of Lincoln while the midday sky went dark and cold and then lit back up as if nothing ever happened. The temperature drops like a storm is coming, but a few minutes later the day is sunny and warm and perfect again. Then you, and everyone else, begin the drive home.

The sun sets and the traffic from the eclipse is still thick, cars driving bumper-to-bumper across the Iowa farmland. Then it begins to rain. It’s your turn behind the wheel, and you won’t reach Minneapolis until well past midnight, but your husband wants to keep going; he’s determined to sleep in his own bed and slog through the workday half-awake. But you are already exhausted and it is only making things worse, so you keep looking for towns with hotels where you can pull off and collapse. You take an exit for Ames, a college town you’ve passed countless times but never seen. He spins the layover as an act of spontaneity, a return to your preferred style of travel: unplanned, barely prepared.

You arrive at the Gateway Hotel and Conference Center, a property of Iowa State University. You won’t find peace here, but you will find rest, which for tonight is enough. You eat in the hotel’s IowaStater Restaurant. The beers are local; the food is a pleasant surprise. Afterward, you watch Colbert’s monologue from your king bed and sleep ten hours before a morning dip in the indoor pool. You use up every last minute of the hotel’s late checkout. You both want another night in this sterile building, where time stands still and everyone is a stranger. Where it feels, in moments, like everything is okay.

Until you remember that the pit in your stomach is not just stress. You are running out of time. The body inside you has to come out.

You’ve gone to fertility specialists. You’ve had your eggs removed and inseminated and carefully placed back inside your womb. Your body once responded so well to a fertility medication that the nurse asked if you were okay having twins. But when the doctor called later that day, he said the medication worked too well. Your body was releasing too many eggs. and if you didn’t take a plan B pill, a pregnancy could put your life at risk. Set against these struggles, it’s a surprise when the miscarriage happens on its own. It requires no procedure, no meds. An ideal miscarriage. You see your midwife at 1 p.m. on a Tuesday, and the sloughing is underway, everyone is satisfied.

At 3:30, your husband calls 911.

He is sick today. He threw up this morning. You are in the bathroom, bent over in pain from terrible cramps, and he is lying on the wood floor outside the door, stripped to his underwear, fighting to stay awake in case you need something. And you do. You are soaking through pads every few minutes. It’s bad, you tell him through the door. Don’t come in. But there is so much blood.

Ask him to call the nurse line. Adrenaline will snap him awake. While he’s on hold, you yell that there’s no time, call 911. He disobeys and opens the door, but you won’t remember this because by now you’ve folded into your own lap, barely awake, naked, and you can’t open your eyes. You live close enough to the fire station that he hears the truck siren as it pulls out of the garage. He squeezes your hand and tells you to stay awake, as if it’s that simple, and when he asks if you can hear him he has to repeat himself three times before you respond, only with a hum, you can’t open your mouth, you might be leaving him forever and there’s nothing he can do to stop the bleeding.

You are awake when the paramedics come through the door. You are not so far gone to allow strangers to find you flopped over naked on the floor; you have pulled on a T-shirt and shorts, but are still too dazed to speak. Because the firefighters never relay your initial blood pressure, the paramedics assume you overreacted. “She was scared,” someone says. They never ask to see how much blood you’ve lost; they don’t turn on the flashing lights when they take you to ER. During the ambulance, ride a male paramedic, commenting on the situation, mentions those online videos of fainting goats. Their dismissal is contagious. It spreads to the ER nurse and the doctor, who treat you with the same dismissive tone. Not until they open your legs to clean you up do they grasp what has happened. Their faces grow more focused, their words more clipped as they begin to clean you up and realize how much blood you’ve lost. The doctor finds a clot lodged in your cervix that caused you to bleed too much, too fast. Later, he sits down and insists you did the right thing by calling 911, but his tone suggests that he’s also speaking to himself, correcting his own false assumptions. The nurse tells you to stay in bed until your IV bag is empty. She has suffered miscarriages, too, and she knows better than to say everything will be okay. False hope will not help you heal. What helps are intravenous fluids and a caring voice that understands. So that is what she gives you.

You will relive these events together, the loss and trauma and fear you both shared. But only one of you was cleaning your own blood off the bathroom floor as more poured out and your vision went dark. One day, you will look back and say you never felt more alone.

Three days after the ambulance ride, you and your husband are on a flight to Portland. The trip was planned before the miscarriage, and in keeping the promise you had made with one another that you wouldn’t stop living life while you struggled to conceive, you went. You both feel half-dead, and your face is still pale from all the blood you lost, but you’re too tired to rewrite the rules, and again, you think there is no right choice.

In Portland you stay with a friend who is pregnant, who had called you after she heard about your loss to tell you, in a tear-choked voice, that not only is she pregnant, but that your due dates—hers and the one you would have had—are just one day apart. You didn’t want to appear resentful by deciding not to stay with them, but as soon as you go to your room for the night, you break down in sobs.

It is supposed to get better with time, but the next day a fire breaks out in the nearby Columbia Gorge. Teenagers with fireworks have started a flame that chokes the city in smoke and ash, making you so sick you spend an entire day in bed. The world’s burning is no metaphor for what’s happened to you, but the poisoned air and blood-red sun make for nice imagery.

You stay home sick, coughing and nauseated all day long, while your husband goes out with friends in the city, where ash is dusting the streets like snow. He tells your friends what happened, and they ask, “Is that why you guys have been so weird?” And that’s the first indication that the two of you aren’t getting by as well as you think.

Back in Minneapolis, back at work, you are asked to lead a series of training sessions for your fellow psychologists. The role-playing script you follow casts you as a female patient who has suffered a miscarriage and is at the hospital to see her doctor. None of the other therapists knows what happened to you. No one knows you’re still grieving your own loss and wondering when you’ll feel better.

The script always ends the same way: the patient is prescribed antidepressants.

And then one day you’re pregnant again. For most people this is the happy ending they’ve been seeking, but for you it marks the start of a new torment. Inadvertently, you have prepared for this. You now know, for example, that the validation of each ultrasound lasts only for five minutes, because by the time you sit down for a celebratory brunch, you are certain you’ve lost it—there’s a cramping feeling at the back of your hip, so much like the period cramps that signal bleeding and loss and starting over.

When you start bleeding at five weeks, no amount of Internet research or insistence from nurses and doctors that “This Could Be Normal” can override the fact that you didn’t bleed the first time around. You’re bleeding the last time you have to endure the role-playing exercise, trying to swallow your own real fear while a fake provider recommends pills because science hasn’t killed the myth of female hysteria.

You discover the symptoms of pregnancy and miscarriage are the same. Every new change is excitement and dread, every moment of quiet a screaming alarm. When you lost the first pregnancy, you knew before the ultrasound tech told you so. You knew when the sickness lifted too early. Your body stopped speaking; you knew.

Now, you are always knowing. Every moment of worry feels like the thirty minutes the two of you spent on a bench in a hallway outside the room with the ultrasound machine, waiting for them to fit you in. You watched expectant mothers enter nervously and exit with a smile. Your husband put his arm around you and said you’d both be okay, no matter what. He said this because by now he knew, too; his body was cold and he was trying not to shiver, and you were very quiet because you knew.

That’s how every moment feels the second time around. Every good moment, every unsure moment bleeds into terror and fear. That you will survive offers no comfort. To survive means to suffer and you don’t want to suffer, you’re not sure how much more suffering you can do. One of your best friends died, and then your father died, and neither of them were there for you when the bloom withered in your womb.

When will it end? It’s ten weeks now. You’re reluctant to engage in the rituals of shopping for strollers or maternity clothes. You tell the news to your family, your nieces, and the oldest one, the empathic, loving seven-year-old, leaps out of her chair in a room crowded with strangers and yells, “YOU MEAN YOUR OTHER BABY DIED BUT NOW YOU HAVE ANOTHER?”

Yes, you say.

I hope so, you think.

Fourteen weeks. They say it’s going well. They print ultrasound photos to take home.

But you know.

The two of you still joke about that conference center in Ames. The bland comfort that satisfied your needs and offered little more.

Twenty weeks.

You’ll go there to mourn the next one, too.