At eleven, I ask Brian if I can take my break early because I’m worried next time the phone rings I’ll say Safe Haven Insurance the way I’m supposed to, then start to scream and not stop. When Brian sees the look on my face he tells me to take as much time as I need. He’s worked here for seven years and he understands how bad Tuesdays can get. Outside, on the ground floor, I call my mother.

“Trisha,” she says. “Is something wrong?” and I want to curl up inside her voice and fall asleep.

“No,” I say. “Nothing’s wrong.” I pick at a thread dangling from the front of my work pants. “Can’t I call to say hello? I miss you.”

“Why don’t you come home, then?” she says. “You get Thanksgiving off, right?”

“I can’t,” I say. “I’m going out of town.” The bottoms of my espadrilles press into the soft flesh of my heels. I wind my toes out though the straps and balance on the soles.

“What,” she says. “You’re spending it with that boy?”

“Boyfriend,” I say.

She snorts. “What’s his name? Greg?”

“Henry. It’s not important. How’s work?”

“If you don’t have anything else to say, I’m getting off the phone. I don’t need to drive into a telephone pole listening to talk to you about nothing.”

She hangs up just as the thread I’ve been toying with comes loose, whipping out a row of stitches on the inseam. Something inside me unravels with it. If I thought she would answer, I would dial her again. I would tell her about the photograph, framed and hung up above a window in Henry’s bedroom. In it, you can’t see his ex-girlfriend’s face, only pieces: black braids swept up and away from the nape of her neck, a smooth rectangle of brown skin, a thin silver cross on a delicate chain pressed against one shoulder blade.

“It’s gone now,” I would tell her. “He took it down and asked me home for Thanksgiving and I had to say yes.”

And she would say, ”No, you didn’t. The only thing you have to do is stay black and die.” So instead of calling her back I stand alone in the parking lot until the sun shines so hot I feel myself start to melt, and then I head back up the stairs.

Henry and I met at a birthday party for the girl in the apartment next to mine, Katie of the golden highlights, the perpetually perplexed expression, the entire weekdays spent asleep beside the pool. She’d tossed the invitation into the air between us while we waited for the elevator to take us down to the lobby. When I showed up at Jones on Third that Thursday night in my cuffed office slacks and white button-down blouse, I understood she’d only been trying to be polite.

“This is Trisha,” Katie offered feebly to her cluster of girlfriends, three versions of each other in varying heights and hair color. They smiled in unison and melted away. I spent the next twenty minutes gazing sullenly at the bartender. Her unwillingness to look in my direction was, I decided, personal. She proved me right when she took the order of the boy behind me over my head.

“I’ll have a Scotch and…what do you want?” He looked down at me, like I was his date. The bartender and I made matching expressions of surprise. When my gin and tonic came, he paid for it.

“What?” he said. “I can’t stand to see a face so sad on a girl so pretty.”

I knew it was a line, but it was rare for anyone in LA to use one on me, so I followed him home. Later that night, my legs wrapped around his naked waist, I told him the secrets you save for people you expect to sleep with once and never see again, the MCAT I’d walked out of, the final exams I never bothered to show up for. Waking up in May my senior year to find that Melanie, my roommate, whose steady supply of prescription drugs had gotten us both into more trouble than I’d ever thought possible, had somehow been accepted to Columbia Law School. Her parents were lawyers in Philadelphia, and they had made some calls. My mother is a divorced home health care aide in Houston, so there were no calls to be made for me, I said, and then I laughed and rolled over, pulled my camera out of my bag to snap pictures of the soft brown of my thighs against his pale white ones, because I didn’t like the look in his eyes, hard and closed up as if he was about to tell me stop feeling sorry for myself, which wasn’t what I wanted to hear.

Still, he called me the next weekend, and then the weekend after that. Instead of bars in West Hollywood, he took me to a French bistro with walls draped in vintage movie posters, big-hipped blonde women and men with chiseled cheekbones smoking cigarettes. Henry had graduated from Harvard four years before and he worked the kind of job you get for going there but not being too ambitious otherwise, as the executive assistant to a man who owned a fleet of private jets. He set his own hours, worked from home, got paid in cash, and, in return, had to fly whenever he was called. His life was as far away from mine as it was possible for someone else’s life to be. I wondered what he saw in me until I found out his father was the chair of the History Department at BU and his mother was a psychology professor at Smith with a famous last name. How proud his wealthy liberal academic parents must have been of their oldest son for dating a black girl. Black girls. The photograph hanging over his window proved I wasn’t the first.

“Who is she?” I asked him, only once.

“Her name was Angela,” he said. “Is.” He didn’t offer more and I didn’t ask. The day I showed up at his apartment to find the photograph gone, he invited me home to Boston to meet his family, and that was good enough for me.

Most days after work, I come home from the office and lie on my side and cry, let Henry stroke my back with one hand while, with the other, he types out emails to his boss. This week, though, Henry is in Seoul, so instead I take a long shower, stand under the spray until my skin wrinkles up and Tuesday swirls down the drain with the cursed phone and my murderous urges. Beneath the steaming flow, I’m reborn into a world without phone sheets. Without shame. After I dry off, I send Henry a text and he calls me long-distance from the cell phone his boss pays the bill for.

“You’re seventeen hours behind me,” he says. “I’m calling from the future.”

“Tell me what happens then.”

“Well. It’s pretty much the same, actually. In the future, I’m still handsome. In the future, you still have nice boobs.”

“Don’t talk about my boobs,” I say.

“Don’t yell at me,” he says.

“I’m not yelling. I’m just talking loudly. So you can hear me. In the future. Tell me more about the future. Tell me it isn’t the same.”

“Well. In the future you’re happy. In the future everything is great.”

“Except we’re both seventeen hours closer to death,” I say.

“Except for that.”

“Well, we’re not,” I say. “You are. I’m still here.”

“I don’t want to die without you,” he says, sounding tired.

“Hush,” I say.

“What’s the matter?”

“What do you think?”

“I don’t understand why you don’t just quit,” he says.

“No,” I say. “You don’t.”

“Hold on another week,” he says. “And then I’m getting you out of there. I promise.”

Tomorrow he comes back from Korea and next Tuesday we go to Massachusetts to spend Thanksgiving at his parents’ house. Henry has a brother and a father and a mom, which is several times more family than I am used to all at once.

After we hang up I open my rolling suitcase and start to pack. But in the months since I started dating Henry, I’ve stopped abusing the Adderall prescription I acquired under false pretenses with company health insurance and started eating again, and so all my dresses have become too small. I lie down on the floor and stare up at the ceiling. I blink and when I open my eyes again it’s morning.

A week later it is the future and everything is not great. Henry’s house in the Boston suburbs is too big and too cold and clean. When I try to speak to his father, it’s like talking to someone over a bad connection. His mother keeps looking at me like I’m something expensive she bought that doesn’t match the picture on the box. I keep answering the questions they ask me about my life in a way that is supposed to be self-deprecating but that makes me come off as insane. Meanwhile, the thought of my own mother alone in her apartment over Thanksgiving is too sad for me to contemplate, and I can’t bring myself to call her.

On Wednesday night, we pull out of Henry’s parents’ driveway, headed into the city where Henry’s best friend from Harvard, Graham, will read from his debut novel at the Brattle Theater in Cambridge. I only agreed to attend because my dislike of Graham seemed less important than getting away from Henry’s parents, and because Henry promised afterward he would take me on a date to get ice cream. Graham lives in LA, like us, but the Cambridge stop on his book tour happens to coincide with my visit. Some part of me suspects this is something Graham has orchestrated on purpose, as if it is his personal duty to be in Boston to show me precisely how much he belongs in this place and I don’t.

At Harvard, Graham and Henry were roommates. They studied Creative Writing together but after they graduated, Graham wrote a manuscript that sold for a quarter of a million dollars and Henry didn’t, so even though they are still close, it’s different. Graham grew up in Beverly Hills and the book, Coldwater Canyon, is about how tedious it is to be rich and white and live in a place where it is sunny all the time. I read some of Henry’s copy on the plane but stopped when I realized Graham’s prose was messing with my thoughts, pressing them into a monotone that made life feel like a movie I was watching. Still, what bothers me about Graham isn’t his writing; it’s the way he looks directly over my head at Henry when the three of us are in a room together, like if he ignores me hard enough I might actually up and disappear.

Since we got in the car, I’ve been feeling wavy, and everything I look at glows. Up to now, I’d thought migraines were for white girls. But whatever is going on inside my head I can’t file under the word headache because headaches aren’t supposed to feel like a fanged animal is trying to birth itself into the world through my eyes.

“Pull over,” I say.

“We can’t pull over,” Henry says. “Graham’s thing starts in twenty minutes.” He turns, and his face looks covered in a layer of glass.

“Pull over,” I say. “Please? I forgot something.” I can’t remember when I developed the habit of lying to get what I want, but now it doesn’t seem to be one I can break.

“Henry, we’re only a block from the house. Turn around,” Henry’s little brother, Mark, says from behind me. Mark, a taller, sweeter version of Henry, is a peacemaker the way other people are redheads or close-talkers—he can’t help it—and I am happy he exists. He’s the only member of Henry’s family besides Henry himself who doesn’t cock his head to the side when I talk, like I’m speaking in a language I just invented.

Henry pulls over. I run down the block, up the driveway and back into Henry’s parents’ house, headed for the downstairs bathroom and the little middle drawer filled with pills. But by the time I reach the front door, my headache is gone. I wonder if the pain wasn’t maybe the warning pulse of a tumor, but then remember my brain already has plenty of non-medical reasons to want to self-destruct. And then I make myself take this thought back, silently, in my head, because I am working on being less dramatic about my feelings. On the first floor, I look around for something to pretend I forgot, but thanks to Jana, Henry’s parents’ live-in housekeeper, the rooms are as bare and sterile as icebergs.

Upstairs in Henry’s bedroom, I find my digital SLR camera lying forlorn at the bottom of my suitcase. I’d bought it off Craigslist in a fit of optimism just before I met Henry, and now, for some reason, it won’t work. I grab it and, on my way out of Henry’s room, I catch sight of myself in the full-length mirror on the closet door. All the weight I put back on after I realized using ADD medication to starve myself just created new problems instead of fixing the old ones stares back at me, so I grab a giant wool sweater to hide beneath and then I run back downstairs. I jump into the back seat just as the sky opens up and a thunderstorm that wasn’t supposed to break until tonight pours down on us through a crack in the clouds.

“Fucking fantastic,” Henry says to the raindrops that careen against the windshield. “We’re going to be late.”

“Don’t be nasty,” I say. “You bought Graham’s book already. What do you need to hear him read it out loud for?” I’m kidding, obviously, but only sort of.

“That’s not the point,” Henry says. I ask him what the point is, then. In the rearview mirror, I see Mark’s girlfriend, Harriet, shift in her seat, obviously uncomfortable. There is a certain type of mousy white girl who finds all black women terrifying, and I’m pretty sure Harriet is this type. Henry and I have been bickering since she arrived at the house this morning, and I know she wishes we would stop. But I can’t help it. I can’t be angry with Henry’s mom and dad so I’ve decided to be angry with him.

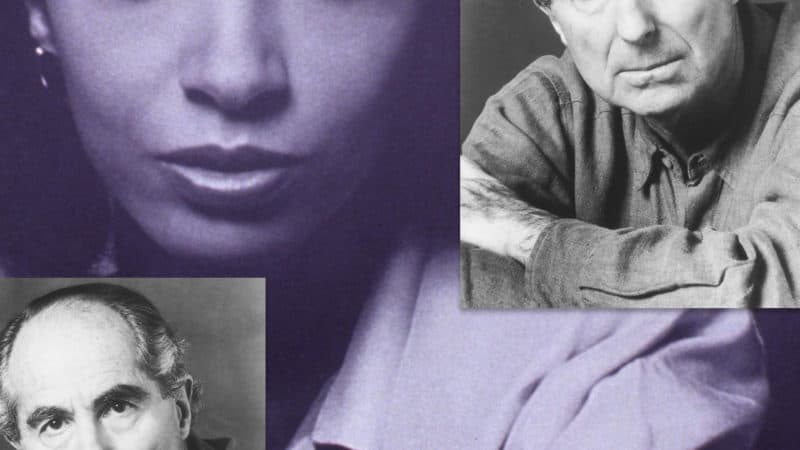

“Anyway,” I say. “The only thing Graham knows how to write about is himself. Why call yourself a fiction writer if you’re just going to write about your own life all the time. He’s as bad as Philip Roth.”

Henry coughs like he’s been punched. “What about Philip Roth?” he asks. He glares at me. Even though he pretends he’s moved on, secretly Henry still wants to be a writer and secretly Philip Roth is his god. His father brought home the Library of America edition of Roth when Henry was ten. The first adult book he read all the way through was Zuckerman Unbound.

“Nothing,” I say, because the fight I’m trying to pick isn’t worth having. Besides, I haven’t actually read any Roth, which is something I think Henry knows. The rain seals the four of us into the car, trapping my anger and leaving it to settle in a cocoon around my body. On the radio, a celebrity whose voice I recognize but can’t place informs us that we are the only people who can stop the senseless clubbing of baby seals. In my lap, I turn the camera off and then I turn it on again. NO ROOM ON CARD flashes across the screen. But there IS room on the card, I want to yell. I deleted half my pictures and the card is full of room.

“No,” Henry says. “Seriously. I want to hear what you have to say about Philip Roth.”

“What?” I say to my hands. “Besides the fact that he’s a sexist, misogynist narcissist?” I’m parroting things I’ve read online and Henry, aware of this fact, laughs in my face and turns back to face the road. I hold my functionless camera up like I am going to use it to club his skull. In the backseat, Mark and Harriet look everywhere but at us. I lower the camera back down to my knees.

It takes us nearly an hour to navigate the line of cars sitting stunned and unmoving on the highway. By the time we get to Cambridge, all the spots near the theater are gone so we have to walk two blocks in the rain. Henry holds out his umbrella for me to share, but I ignore him and walk ahead, concentrating hard on not sliding on the wet cement. One thing about Henry is that he is incapable of holding a grudge, but I cup mine inside me like someone protecting a tiny flame.

“You missed the reading,” says the usher when we get there. “He’s doing a Q&A now.”

“Fine,” Henry says, not looking at me. “Can we go in?”

“It’s full,” the usher says. He pulls open the door to the auditorium to show us. It’s crowded with people standing and sitting on stairs, filling up the aisles and leaning against the walls.

“We’re on the list,” Henry says.

“What list?” says the usher. “There isn’t any list. There might be some space on the balcony,” he points up, like he is doing us a favor. We sit down just in time to hear the audience erupt into cheers. On stage, light skates over Graham’s face, highlighting his pale baby-smooth skin, his chipmunk cheeks and blue eyes.

When the Q&A starts, Graham calls on a man with a shimmering shaved head and thick, black-rimmed glasses. I can see the hero-worship glinting on his face from twenty feet above.

“Hey Graham,” the man says, “Your book changed my life. It’s incredible how well you capture the mood of the era. I have to ask, though. How much of it is autobiographical? I mean, is Luke Flynn you?”

Luke Flynn is the disaffected main character of Graham’s novel. The New York Times called him the voice of his generation, which I think says a lot more about what the Times thinks of this generation than it does about Graham.

“Clearly,” Graham says. “Because clearly that is what the definition of fiction is. Me, writing about myself.”

“Well.” Says the man. He sits back down.

“That wasn’t very nice,” I whisper to Henry.

“He doesn’t have to be nice,” Henry whispers back. “He’s Graham. Anyway, it was a stupid question.” I don’t understand what the one has to do with the other and I say so, but Henry shushes me and I spend the rest of the Q&A feeling indignant. When it ends we ride the surge of smiling, North Faced college students out into the street. The rain has let up, but the air is still damp and colored with sunlight that filters in like weak tea.

“Now what?” I say. I am expecting Henry to say “ice cream,” because he promised, but before he can, Graham is standing next to us. With him is a friend with bone structure like someone tapped at a block of marble for a hundred years until the stone fell away and what was left was his face. The friend is tall, in a rain-spotted silk tie and a black suit that looks expensive.

“Henry, this is Quentin,” Graham says. Henry and Quentin shake hands. “And this is Henry’s girlfriend.” Graham and Quentin nod at me. “Quentin is in law school here,” Graham announces to all of us.

“Hey. Good job man,” Henry moves past Quentin to clap Graham on his back. I wonder if I’m the only one who notices the way his eyes squint more than usual when he touches him, as if he is in pain. “You were great up there.” He takes a step back and says “No, but seriously. Tell me. Are you Luke Flynn?”

Graham laughs. “I got the same question in Brooklyn, too. And in Iowa City. I’m going to start wearing a nametag so next time somebody asks, I can point to it.”

“I’m having a few people over,” Quentin interjects in a satiny voice that reminds me of music, “to celebrate. Just some crackers and wine, that kind of thing. No big deal.”

“Sure,” Henry says. “Fun.”

“But I thought—“ I say, then shut my mouth and don’t say anything else about ice cream. Everyone is already walking down the sidewalk in rows of two, Graham and Henry, Harriet and Mark, and me and Quentin bringing up the rear.

“So how did you two meet?” Quentin asks me politely. A question with enough other questions stacked inside to fill a library basement. Who are you? Where did you come from? If you two get married, will you name the children something other people can spell? Normally, I would lie and say we met through a friend from Harvard, so I could watch as the line of questions percolating behind his eyes changes. No, I’m not just a phase Henry is going through. Yes, the children will have pronounceable names. But I’m tired today and I don’t feel like proving anything to anyone, so I give him the version that is closest to the truth.

“At a birthday party,” I say. “For a mutual friend.”

We pass through the Harvard gates. The air shifts suddenly, and the red brick library comes into focus. Even the light that falls over the buildings here is more defined. Up ahead, I see Graham and Henry visibly relax, like finally, they are home.

“What are you up to these days?” I hear Graham ask Henry.

“You know,” Henry says. “This and that.”

“You working?” Graham asks.

“As we speak,” Henry says, tapping out a text on his phone.

Mark and Harriet walk in front of us, not saying anything, holding hands and staring at the sky. Mark smokes a great deal of pot, so it’s hard to tell sometimes whether he is in a trance or just stoned. Harriet, freckled and moon-faced, graduated from Boston College last year with a degree in medieval literature. I think she’s confused about what we’re doing here, unable to understand how anyone could get so excited about a book written after the year 1500. Both of her parents are doctors and I wonder, sometimes, what it might feel like to be her, to have both the enormous self-confidence and the financial security it would take to devote one’s whole life to Old French poetry.

We follow Quentin across Harvard’s campus and onto a residential street, slick with rain. The houses here look permanent and monolithic, as if they grew up from the ground a thousand years ago, and then waited for civilization to build itself up around them. We stop at one on the edge of the block that looks like a fortress.

“I know,” Quentin says when he sees my face. “It’s not mine. I’m housesitting for the head of the department. He’s taking a sabbatical to work at The Hague.”

Harriet and Mark and I cluster around the front door and peer inside. The pale wood floor spreads out around us from the entryway, shimmering and flawless like the surface of a lake. If I step into it, I am certain I will drown. But then Quentin and Henry and Graham walk into the house in front of us laughing, shattering the still. Music drifts in from somewhere on air that smells like the inside of a museum.

“A few more people are going to drop by in a minute,” Quentin says. “Friends of mine from school. They wanted to meet you, Graham. I hope that’s okay.”

“Why would they want to meet me?” Graham asks.

“Ask them when they get here. Can I give you all a tour?” Quentin says.

In one corner of the drawing room, a teen-aged boy plays the piano. When I walk over to him he looks up at me with kind eyes, then reaches up to turn the page of his music. I am trying to work out what the deal is, whether he lives here or if Quentin rented him for the evening or what, when Quentin calls us all upstairs. The house has three bedrooms, and in all of them, I keep expecting a photographer to step out of a closet and set up his umbrella and reflector, start shooting for Town & Country. I stay near the back of the group, next to Mark.

“This is confusing,” I say.

“I’m glad you think so too,” he says. “My grip on reality is tenuous right now. Listen, I’m sorry things got weird in the car. I learned young that life gets easier when you accept the fact that Henry and my father are both always right.”

“Sure,” I say. “It’s fine.” The fight in the car feels very far away, like it happened to somebody else. I still feel angry, but it’s about something different now. Something whose edges I have to think around because I don’t know what will happen if I stare directly into it.

Quentin leads us back downstairs through the open back door, and out into the yard, where a caterer in a black silk vest with shining gold buttons holds out glasses of champagne on a tray.

“No, thank you,” I say. Last time I drank when I felt this out of my element, I started a fight. I still don’t remember what I said, only the way Henry looked at me that morning and all the next day, like I was a stranger with the face of someone he’d once loved.

Harriet and Mark each take a glass and we step out onto the back porch, into a web of sticky air. On a wrought-iron table sits a platter of dates wrapped in prosciutto, a handful of crackers and a wedge of blue-speckled cheese. I eat a date, and watch Henry slap at a mosquito on the back of his neck then scrape absently at the streak of blood it leaves behind. Graham has pulled him aside to tell a story about something that happened on his book tour in Paris, an anecdote that involves much waving of arms on Graham’s part, while Henry nods politely, looking sad. A caterer brings out glasses of red wine on a tray and I take one to have something to with my hands. I take one sip and then another and then somehow the entire glass is gone. I replace it with a second one, which disappears just as quickly.

“So what do you do?” Quentin has appeared from nowhere to stand beside me in the yard. “In Los Angeles, I mean.” His glossy hair tumbles over his forehead like an ocean wave. His silk tie gleams. It occurs to me that this landscape filled with real live characters from F. Scott Fitzgerald novels and boys with faces out of Dutch paintings has existed for my entire life, but without Henry I would never have known.

“I take off my clothes for money.” I set my wine glass on a nearby tray and replace it with a glass of champagne. A raspberry lolls at the bottom like a wet marble. I concentrate on getting the berry to roll down the sides of the glass and into my mouth.

“Like for performance art?” he asks.

“No,” I say. I swallow the raspberry. “For men. For money. At a bar.”

Quentin’s outline wobbles. I squint at him.

“I had a rough childhood,” I say. “Like many women in my field. My mother—But it wasn’t her fault.”

“Do tell,” Quentin says, though he sounds as if he would like nothing less.

“My mother used to lock me in the closet.”

Quentin’s smile is a gray line stretched tight.

“One night, she forgot about me. This was summer in Texas, and we didn’t have central air. She used to leave a digital clock in there, for light, and I remember watching the red numbers turn. An hour passed. Another. At some point, I guess, I passed out. The next morning, when I woke up, she was gone.”

“Does anybody need a refill?” Graham says. He and Henry are back, standing at the edge of our little pairing.

“I’m good,” Quentin says. I make eye contact with Henry and keep talking.

“She didn’t find me until that night, after she got home from work. I’d been locked up for almost an entire day. I was so dehydrated, I could have died. I had to go to the ER and everything.”

“Hey.” Henry puts his arm around my waist and looks at my empty champagne glass. “What number is that for you?” I shrug his arm off and take a few steps away.

“I was six,” I say. “Like I said, though, it wasn’t her fault. My dad left when I was a baby, and her mother was crazy, too. She did the best she could.”

Quentin shudders. “I’ll bet there are a lot of stories like that one in your line of work.”

“What?” Henry looks confused. “Trisha? What did you tell him?”

“Nothing,” I say. “We were talking about our careers. He asked me what I do.”

“She tells me she’s an ecdysiast,” Quentin says.

“She’s not a stripper,” Henry says quietly, into his glass. “She’s a temp. At an insurance agency. Data entry. Answering phones.”

Quentin looks from Henry to me, trying to figure out what the most politically correct course of action would be. “Henry,” he says. “It’s okay. I mean, it’s her body. She can do whatever she wants.”

“Trisha,” Henry sounds stern in a way I find offensive. “Tell him.”

“Tell him what?” I say, not looking at anyone. I refill my glass from the bottle of Moet some thoughtful person has left out near the hors d’oeuvres. After that, for the rest of the night, it’s as though a window has gone up, and on one side of it is everybody else in the yard, and on the other side is me. Mark, I can sense, is still on my team, but he’s too stoned to be much help and Harriet is a mystery who only talks when Mark does. After the party, we give Graham a ride to his hotel. All the way home, I can feel his body pressing away from mine, towards the edges of the car.

Back at Henry’s parents’ house, the silence is a curtain hanging in the air between us.

“Unlike some people,” I say, when I can’t stand it any longer, “at least I can tell a good story.” I’m thinking of Graham and his terrible novel, but I realize too late that Henry might think I’m talking about him, about his fledgling college writing career that never took off.

“Do you have to be this weird all the time?” Henry asks, pulling his shirt off over his head. “I don’t know if anyone ever told you this, but it gets boring after a while.”

He climbs into bed and turns off the lamp on his nightstand and when I wake up the next morning, it is Thanksgiving and I am alone.

I walk downstairs to look for Henry but the house is empty, the kitchen floor freezing against my bare toes. I pick at a bunch of fat purple grapes someone washed and left in a silver bowl and lean against the counter, feeling sorry for myself. I hear footsteps on the stairs and I wonder if they are Henry’s and if they are, what will happen now. The fight we had last night feels both final and unfinished in a way I can’t yet define.

Harriet materializes in the doorway, her thin brown hair drifting in a listless mass from a rubber band at the top of her head. She rubs her eyes and yawns when she sees me. She seems surprised that I’m still here.

“Where is everybody?” I ask. Around us the kitchen is cold and white and antiseptic, tinted with the smell of Henry’s mother’s face cream.

“Mark and Henry went to get stuff for Thanksgiving brunch. Brioches or something. The bakery’s in Natick. He didn’t tell you?”

“He might have,” I say. “I wasn’t exactly lucid this morning.”

“I’m going to the drugstore to pick up some tampons,” Harriet says, surprising me. It’s the first time she’s spoken to me directly since I got here. After what happened the previous night, I guess she’s realized I’m not substantial enough to be a threat. “There’s a place over there where you could get your camera looked at, if you want to come.”

“Sure,” I say. I follow her outside. Her tiny black Honda overflows with a sea of empty diet Coke cans, binders, loose papers and half-graded exams. I remember Henry telling me she teaches French at a charter school in Framingham, part-time. I sweep a wave of tiny, brightly colored scissors off the passenger seat and onto the floor.

“How do you like it?” I ask her. “Teaching.”

“I don’t know,” she says. “It’s fine, I guess. I started doing it to make my Ph.D. applications stronger, but now, I might put off applying until next year. It’s better than I thought it would be.” Outside, ancient, massive trees sweep by, and then a lake, a plowed field. Harriet parks in an empty strip mall anchored by a Dunkin Donuts and a CVS. On the far end sits a store called Doug’s Camera and I head towards it, broken camera in my hands, telling Harriet I’ll be right back.

When I walk inside, a bell on the glass door tinkles. A man I assume is Doug organizes film canisters behind a glass desk. I pause in the doorway and try to remember the last time I saw actual film.

I tell Doug about my camera and he hooks it up to his computer. A parade of photographs I’ve never seen before dances across his screen. A white girl, eyes caked in thick black eyeliner, stands posed with a life-sized cut out of Jesus. In some of the pictures her hair is blonde. In others it is yellow or pink or green. There she is in a park. In front of a statue of a Woolly Mammoth. In a high school cafeteria. The girl smiles with her lips closed, but she seems happy.

“Friend of yours?” Doug asks me.

“No,” I say. “I bought this thing used.”

“Well there’s your problem. Somebody else’s pictures clogging up your memory. Let’s get rid of that.” He presses a button on the keyboard that selects all the photographs, and then he hits delete and they are gone. “That should be much better.”

“Thanks,” I say. “How much?”

He waves me away. The bell tinkles again as the door shuts behind me. Above me, the sky feels low and heavy, like if I reached up I could tear a hole in it and climb through to the other side. At CVS, Harriet is up front at the register. She has tampons, but she’s also grabbed dry-erase markers, construction paper in primary colors, glue. She laughs lightly when she sees me and shrugs.

“I can’t help it. I see this stuff and I have to buy it. It’s like, Pavlovian.”

I imagine Henry’s family around the giant mahogany dining room table with his grandmothers and his mother and his father and his brother. I wonder if they’ve noticed yet that we are missing, and how long they will wait for us to return.

“Hey,” I say. “I have an idea. Want to go into Boston? Like we did last night? But just us this time?”

Harriet looks unsure.

“Come on,” I say. “Don’t act like you couldn’t use a break.” I snatch Harriet’s keys from her hand, where she’s been cradling them alongside her phone. “I’ll drive.”

To my surprise, she goes along with it, at least at first. I pull out of the parking lot and onto the highway in the wrong direction, away from Henry’s house, towards the city. Next to me, I feel Harriet wondering if I have a plan. In Harvard square, we park and look around for a record store or a Starbucks to go into, but their windows are all dark, closed for the holidays. It’s only four in the afternoon, but evening is already settling in. We walk in the quiet for blocks and blocks, but nobody appears. Streetlights blink on, one by one. We pass a Denny’s, the glow of its cheerful yellow sign pathetic and useless in the gloom.

“Hungry?” I ask Harriet. She looks up at me and for the first time, I can see that she’s afraid, of me again, or for me, I don’t know. Inside, the white hostess doesn’t try to hide her surprise. Alone, Harriet might be mistaken for a college student alone in Cambridge for the holidays, but I add an extra layer of complexity. Luckily our waitress is matter-of-fact and no-nonsense, ultimately as uninterested in us as we are in her.

“Y’all want some coffee?” she asks.

“Hot chocolate,” I say. “Yes. And I’m ready to order. I’ll have pancakes. And eggs over easy. And home fries. And—Harriet what do you want?”

“I want to go back,” she says. In the greasy fluorescent light, she looks suddenly ill.

“What?” I say.

“I’m not supposed to be here. I want to go back,” she says again.

The waitress taps her pen against her pad. “You need a minute?”

“This is stupid,” Harriet says. She sounds like a petulant child, but still, I notice she said “I” and not “we.”

“Fine,” I say. “Go back.”

She stares up at me with pale grey eyes and grips the edge of the table.

“You want to go back so bad, then go,” I tell her.

“You’re being ridiculous,” she says, standing up.

“I want to go back, too,” I say to her. “I want to go back as bad as you do. I just don’t want to go back there.”

“Then where?” she asks.

But I’m not sure how to answer, because I’m thinking about my mother, angry and alone in her apartment, about the red numbers of the digital clock in the closet turning one by one, about Angela, Henry’s ex-girlfriend who looked both too much and nothing like me, about the girl in my camera, about Philip Roth.

“Are you coming or not?” Harriet asks.

When I don’t say anything she leaves. I hear the whoosh of the November wind as she lets the glass door swing open into the night. I follow her out into the empty evening and hand her the keys. In the passenger seat, I flip through my old photographs, looking for traces of the girl, but she is no longer there.

If Henry and I break up and never speak again, the version of me that I am now will live forever in his head. I’ll be a forty-year-old woman somewhere with kids and a house, or with no kids and no house, and, either way, a younger me will be alive inside his memory, exactly the way I am now, for always, immortal, like this.

When we get back to Henry’s parents’ house, the kitchen is filled with the smell of catered sandwiches, chicken and mayonnaise and tiny French pickles on big pale chunks of baguette. Henry’s mother is telling everyone to leave them alone, but Mark is gnawing on one. “What?” he says. “I did all the work and now I can’t reap the rewards?”

Next to him, Henry holds a white plastic bag with the words Barrow Street Bookstore written out across it on both sides in script. Harriet and I hover on the edges of the little family bubble awkwardly until he turns around and notices we are there.

“Surprise,” Henry says. “We stopped in Concord. I got you these.” I reach inside and pull out The Ghost Writer and The Human Stain. When I look back up at him, Henry’s eyes darken. “You don’t have to read them if you don’t want to.”

“No,” I say. “I want to.”

I mouth the words I’m sorry to him across the kitchen island, and a few minutes later Henry excuses himself from his family, and follows me upstairs. In his bedroom he doesn’t give me time to take my clothes off, just pulls down my jeans and turns me over so my chest is against his bed and he is behind me with his hands on either side of my waist, the way we used to after we first met and his hands were the most important thing.

“Calm down,” I say from beneath him. “You’re hurting me.” He isn’t really, and it doesn’t matter anyway because he doesn’t hear. He’s busy trying to tell me something. He wants to make sure I understand. “Trish, I love you,” he says into the back of my neck. And what I want to say is that I know that, that I knew it already. But I also know that love is not the only thing, and all by itself it is never enough.