My favorite dessert is carrot cake, though I’m not sure exactly when or why this happened. I never seek it out, but often find it. I have neither a favorite recipe nor purveyor. My preference is that it contain walnuts. Raisins I could take or leave. I have never actually baked one myself and don’t have a cake pan. I am, generally speaking, trying to go easy on the carbs.

We all have our indulgences; the price we are willing to pay. It’s easy to imagine that carrot cake’s is something of a bargain. The vegetal aura, the warm, unthreatening spice—it seems (questions of dessert tend to slip sideways around rational thought, into realms of baseless intuition) almost monastic where nutrition is concerned. The carrot, taken on its own, I associate most closely with crudités edging toward room temperature on lonely tables at a chaperoned dance. The shredded carrot, postiche of shitty salads, is particularly useless for self-indulgence. The very word feels like repentance. It’s hard in the hand — a small, smooth stone hurled through a window at the lab where they fry our taste buds, dunk us by our ankles in triglycerides. Just the carrot cake, for me. The carrot is simple. It is honest and demure.

But rhetoric, as the ancient saying goes, holds sway only from the palate up. The facts on the ground are that the standard carrot cake recipe involves somewhere between one and three pounds of sugar, inclusive of the frosting, which, along with cinnamon or nutmeg or whatever else you feel like putting in, is most of what you taste. The carrots themselves are more of a texture thing, and keep the cake moist, being primarily (88 percent, for the completists) made of water. So, on the one hand, I’m lying to myself. On the other, that’s essentially how this works.

It was not always so. Carrots have a decent amount of sugar in them—nowhere near what we’re accustomed to (annual per capita consumption of caloric sweeteners in the US stood at 128 pounds in 2016), but enough that they’ve been used in desserts for a good chunk of recorded history. The earliest documentation of a proto-carrot cake comes via Abu Muhammad al-Muthaffar ibn Nasr ibn Sayyār al-Warrāq, who, a thousand-plus years ago in Baghdad, wrote a cookbook. It is a masterpiece of recipes, poems, jokes, and anecdotes entitled The Book of Cookery, Preparing Salubrious Foods and Delectable Dishes Extracted from Medical Books and Told by Proficient Cooks and the Wise. Among its 132 chapters are four dedicated to the Khabis, a kind of pudding or custard, and among those are a couple with carrots. One calls for sliced carrots to be softened in milk, flavored with cloves, cassia, ginger, nutmeg, and spikenard (which used to be all the rage—Achilles anoints the body of Patroclus with it in the Iliad), then thickened with egg. The other brings dates to the party. Both actually sound pretty good.

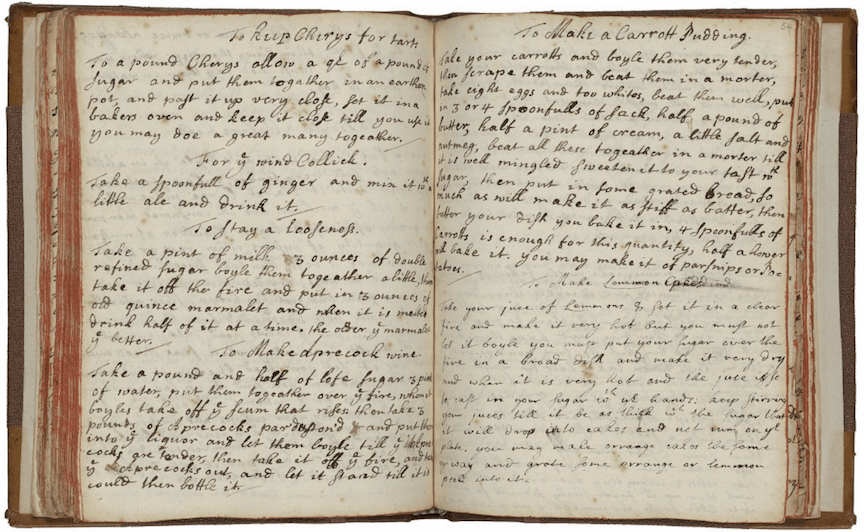

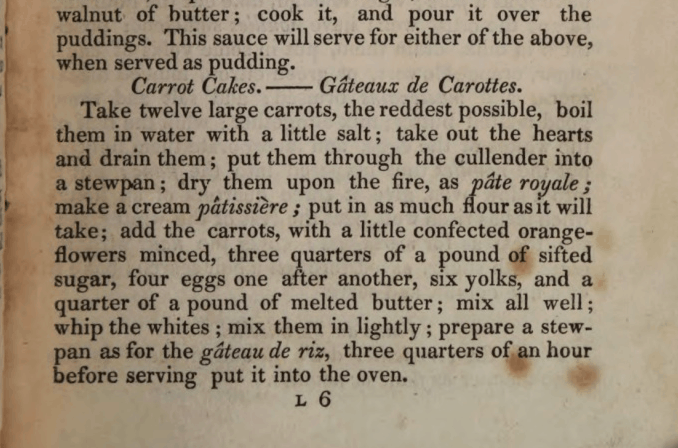

Similar dishes continue to crop up over the centuries in the form of puddings, approximating what we’d recognize as an unfrosted cake. Constance Hall’s endearing, hand-written 1672 cookbook has an entry, “To Make a Carrott Pudding,” baked with eggs, butter, cream, salt, nutmeg, breadcrumbs, and boiled carrots. A century later, George Washington was offered something similar when he hosted a feast at Fraunces Tavern in Manhattan after the final British evacuation in 1783—carrots, butter, flour, eggs, cinnamon, and nutmeg. (The tavern is still there, so I went by and checked: Washington’s face is plastered all over, but carrot cake is off the menu.) The early-nineteenth-century Art of French Cookery by Antoine Beauvilliers calls for boiled carrots, flour, eggs, sugar, butter, and orange flowers, baked for forty-five minutes and served plain. For hundreds of years the recipe had more or less remained unchanged, having reached what could be presumed its ideal form. These are delicate, thoughtful cakes, unfrosted save for an occasional dollop of cream. They’re dignified, restrained, civilized. Things might have kept on like that were it not for Hitler.

American business has always been a kind of freak show in general, but the things we do to food are really something. To take one famous example, we engineered tomatoes to look perfectly smooth and beautifully red, and in the process made them taste like wet sand—which is to say that we don’t meet demand so much as manufacture it, so that eventually everybody forgets what came before. The Second World War is where the path of carrot cake branches, where the American propensity for lunatic entrepreneurial freelancing takes over and I find myself staring at a half-eaten slice, bewildered. It is, if you will indulge me just a moment, the fork in the road.

In early 1942, when the American government started rationing goods, first on the list was sugar. Pretty much everything else followed shortly thereafter. But with US forces all over the globe, from Europe to the Pacific, quantity wasn’t the only issue—there was the practical matter of transportation and spoilage. In stepped industrialists contracted by the government to sort out logistics. One of them was George C. Page, a Nebraskan farmboy who’d moved to Southern California with a couple of dollars in his pocket and a sincere desire to be rich. Page washed dishes in a restaurant until he’d saved up enough to rent a storefront, then started a company called Mission Pak, shipping California oranges to people for Christmas.

Page made a killing after Pearl Harbor by buying up warehouses and renting them back to the war effort. Northrup and Hughes Aircraft built planes in his buildings, and he made another fortune jacking up the rents on their short-term leases because it was too much of a hassle for them, what with all the machinery, to move. He bought up the Malibu beachfront, which people were abandoning for fear of Japanese invasion, and turned it around at a massive profit once it was clear they weren’t coming. He volunteered to fight, but the government sent him to Berkeley instead. He would learn how to dehydrate food. Studs Terkel interviewed him for his oral history, The Good War: “I reasoned that dehydrated products were so concentrated that there would be a good demand after the war as well.”

He was wrong. Frozen foods got hot, but nobody wanted the dehydrated stuff. When the war ended, the government slipped out of his contracts, and he was stuck with a warehouse of dehydrated carrots.

Angelinos might be familiar with Page because, annoyed that the La Brea Tar Pit fossils were housed seven miles away in the Natural History Museum and not right by the sludge where they’d ingloriously struggled and died, he built the George C. Page Museum that sits there now. I know him because I eat my anxiety. Saddled with a mountain of carrots, Page called his old boss from the restaurant he’d worked as a teen. “He took some of those tins off my hands and came up with the idea of the carrot cake. It became so popular that other bakers used it. Every pound of those carrots was taken off my hands. I got out of everything.”

So began the popularization of carrot cake in America. Things built slowly at first, then exploded in the late ’60s, when carrot cake was finally mated with the cream cheese frosting so ubiquitous now. It was a fad food—the carrots and chopped nuts convincing everybody it was basically a salad, driven on by Philadelphia Cream Cheese’s marketing efforts. You might think of carrot cake not as a way to prepare carrots but a way to get rid of them.

I still can’t help but think of carrot cake as an honest sort of food. I think of all the vaguely autumnal desserts this way—pecan pie, for example, strikes me as a legitimate thing, organic, born of a proud culinary tradition and centuries of evolutionary tinkering. But pecan pie, as we know it, was essentially invented by corn syrup manufacturers, just as Adams Extract turned food coloring into a red velvet phenomenon. There are a ton of these Frankenstein desserts, though most have fallen by the wayside over the years. Campbell’s jumped on a depression-era stopgap of using tomato soup as the basis for a cake (which functioned much as carrots are supposed to, keeping things moist and imparting a little sweetness). Propelled by magazine ads and the company’s suggestions, it had a moment about the same time that carrot cake took off—tomato soup cake was the first recipe Campbell’s ever published right on their cans—but never quite caught on. Soup cake, I suppose, doesn’t have much of a ring to it.

The carrot cake that emerged from the ’60s, with its ridiculous little sugar carrot decoration, is a fake, a fraud, an absolute disaster calorically speaking, but somehow, still, my favorite. That is not nostalgia. There were no carrot cakes at holiday dinners with my family. I’ve never had carrot cake for my birthday. Never split a slice with a woman I was falling for. In fact, I could not describe for you any particular thought or feeling I have ever had while eating carrot cake, nor pinpoint any dates or times, nor distinguish one slice from any other. I can’t seem to remember ever having eaten it at all. Carrot cake is my favorite dessert, but I have no memory of it. What I remember instead are Wayne Thiebaud’s cakes, those perfect cylinders, gleaming immaculate shellacs smiling from behind the glass, their little dunes of pigment catching just a hair of light.

What comes after I want no part of. The first half of a piece of cake you can eat without realizing what you’re doing. The second half is where I get into trouble. Craving, then the flash of anger. The tar pit pulling at your feet. My eyes are always bigger than my stomach, though not always for lack of trying. It’s annoying, to be fooled and fooled again by what is by now a pretty old and predictable trick. But then, on the subject of rhetoric: in Welsh, the word for carrot is moron.