Two months ago, in preparation for my conversation with Stanley Nelson, a publicist for his production company, Firelight Films, sent me the password to access his latest film, Freedom Summer, online. The film documents the coordinated effort to register black voters in Mississippi and send the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to the Democratic National Convention during the summer of 1964. The publicist asked that, after viewing the film once, I delete both it and the password. Thirty views later, Freedom Summer is still on my computer.

The entire documentary is captivating, but the stretch where the volunteers and the SNCC folk, led by the local residents of Mississippi, are singing their version of “This Little Light of Mine” is the most healing five minutes of art I’ve experienced in a long, long time. I feel at the center of everything Stanley Nelson is exploring in his film. And most importantly, I don’t feel alone in that center. You’re there with me, and we’re surrounded by hurt people, trampled people, beautiful sweaty black people from Mississippi filled with will and imagination, but so desperately in need of healthy choices, second chances, and art unafraid of nudging us toward freedom. Freedom Summer reminds us that our movement is present, and that the only reason we are wherever we are is because someone in Mississippi loved us enough to fight for the little bit of freedom we have. The film doesn’t simply remind me of home; it reminds me in absolutely brutal sight and sound why James Baldwin wrote, over fifty years ago, “I had said I was going to be a writer, God, Satan, and Mississippi notwithstanding.”

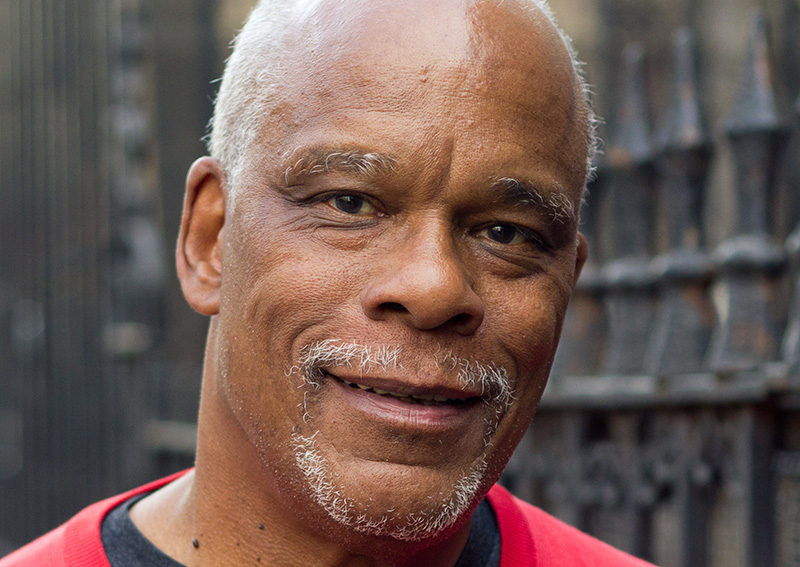

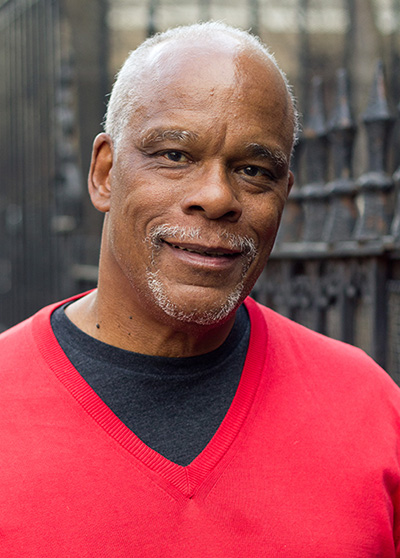

Nelson has directed a number of films, including Wounded Knee, The Murder of Emmett Till, Jonestown: The Life and Death of People’s Temple, and Freedom Riders, which Oprah Winfrey highlighted on a show celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the legendary activists. His work has garnered him a MacArthur “genius” award and an Emmy.

We met in his Harlem home, where I entered hoping to have enough courage to tell him thank you for loving us.

—Kiese Laymon for Guernica.

Kiese Laymon: Growing up in Mississippi, you see hundreds of renditions of Freedom Summer. So when I heard about this documentary, I doubted that you could possibly show us something different. But you did. Did you discover anything you didn’t know in the process of making the film?

Stanley Nelson: We really wanted to make sure we covered the Mississippians who were already there on the ground and give them their due because in some ways, they’re the real heroes of this story. The volunteers and the SNCC folks were important, but the folks on the ground in Mississippi had been struggling for a hundred years. They had the most to lose. They’re the ones who have to stay.

Kiese Laymon: I was surprised at how the film did a great job of showing the pressure a lot of the Mississippi black folks felt from the white people they worked for.

Stanley Nelson: Usually we look at it like, “Oh, black people couldn’t vote in Mississippi because they had to take a literacy test.” But one of the things you learn in the film is that there were major consequences for even trying to vote. You could be killed for trying to vote. You could definitely be fired from your job and many were, which is why so few black Mississippians even attempted to register early on. They put your name in the newspaper if you tried to register to vote.

That’s why there was an extra foot on your neck in Mississippi. There was the realization that if black people got their rights, then things could really change there.

Kiese Laymon: We’re sitting in a studio in Harlem. Talk to me about your desire to explore Mississippi when some might argue there’s a New York history that also needs to be explored.

Stanley Nelson: Early in my career, I did a film about Marcus Garvey and another one on Madam C.J. Walker. But one of the most important things for us to say about Mississippi is that it was 50 percent black. That’s what made Mississippi different from everywhere else. That’s why there was an extra foot on your neck in Mississippi. There was the realization that if black people got their rights, then things could really change there.

Kiese Laymon: Tell me about your first experiences with Mississippi.

Stanley Nelson: First time I went to the Delta, I had this realization that there was nothing there that I knew. There was nothing I knew. There’s this quote in my Emmett Till documentary where a guy says, “The Delta is the most Southern place on earth.” It is. People describe the North and the South. Then they describe the South and Mississippi. Then they describe Mississippi and the Delta. Those are separate places, man. It’s amazing how separate, how different they all are.

Kiese Laymon: Black women in your film are explored with a particular kind of depth I haven’t seen in many other films of any genre. From, of course, Fannie Lou Hamer to folks like Daisy Harris, whom most people have never heard of. How did you find these black women who were so integral to the movement?

Stanley Nelson: To tell the story truthfully, we had to do it. We wanted to find black women who were central because they really aren’t given their due in many other films about the movement. For example, one of the volunteers said, “The man of the house never got comfortable with white women in his house.” Daisy Harris, one of the women in the film, said, “It was my decision whether these people came in my house or not.” You had these black women, not just organizing, but making a lot of the decisions that actually made the movement possible. But too often they get written out of the history of the decision-making.

I want to be able to tell black people something they don’t know, something about our own lives.

Kiese Laymon: Who do you make your films for?

Stanley Nelson: I want to be able to tell black people something they don’t know, something about our own lives. I just came from Bedford Prison and talked to these women in their documentary class. Someone asked me, “Who do you make your films for?” I said I make my films for black people. If I can tell black people something new about Emmett Till or Freedom Riders or Freedom Summer of the Black Panthers, well, then, of course I can tell the white people something new. I also want my films to entertain. My job isn’t just to tell you something. My job is to entertain you and make you stay long enough to learn something.

Kiese Laymon: Can we talk about the importance of music in the movement? When you went down there, did you know that music was so important to the movement?

Stanley Nelson: We did. We knew that music was really important and wanted to give you that sense as much as we could.

Kiese Laymon: There’s that scene in the church during one of the mass meetings, and someone starts singing “This Little Light of Mine.” And the song goes on for about four minutes as you take us through different scenes and different voices. It’s breathtaking. Can you talk about the decision to allow the song to go on so long?

Stanley Nelson: One of the most important parts of the civil rights movement that people don’t talk about was these mass meetings. It’s like “Movement Church.” It’s a combination of the music of the movement and the church. Those mass meetings are where people got the energy to go on to the next day. Instead of feeling like there’s two or three of us in this town of hostile crackers, I’m in a big church filled with people who believe the same thing I believe and the power of song is raising what we’re trying to do, raising it up to the rafters. We spent a lot of time on that scene. We actually went back and remixed that scene and I kept saying to the sound guy, “Louder. Put the music up loud as you can.” As the voices beneath the music are talking, you find that the music is just as important as what they’re saying. The traditional thing is to lower the music so you can hear the dialogue. We just couldn’t do that for that song.

Young people today have never seen a movement work.

Kiese Laymon: When you look at the nation today, do you see the crumbs of any kind of movement that could rival what happened during Freedom Summer? And is it wrong for us to expect that kind of movement given the way new media runs everything?

Stanley Nelson: My generation didn’t pass the movement on. Young people today have never seen a movement work. Think about that. They’ve never seen a social justice movement actually work. And we haven’t effectively told them our story. We haven’t shown them how our story is their story. As black people, we want our story to be this constant ascendance from slavery. But it’s not like that. You push and it goes up. Then there’s a backlash, and if folks stop pushing, it goes down. Let’s face it, it’s a lot more complicated today. Part of the problem with Occupy Wall Street was that folks were never really clear on what they were fighting for. If you don’t know what you’re fighting for, how do you know when you’ve got victory? In some ways, new media makes it easier for people to connect. It’s hard, though, because we’re much more seduced by the Internet, by big-screen TVs, by cell phones that can do everything. I read this article this week about how poverty in our country is peculiar because it’s marked by big-screen TVs, cell phones. Makes you wonder if all of it is just another way to seduce people whom we don’t want to rebel.

Kiese Laymon: If we’re going to be seduced by big-screen TVs and movies, are you trying to create art that counters that seduction?

Stanley Nelson: That’s good. Can we use that as part of our motto?

Kiese Laymon: Yes, indeed. When you looked at the murders of Trayvon and Renisha McBride did you think that would spark a movement?

Stanley Nelson: I hoped that there would be more coming out of it, but I understand our history. Those are little steps on the way. Emmett Till was killed in 1955 and the movement as we know it didn’t start until 1961. One of the most interesting things I’ve heard from folks in Freedom Summer, no matter if they were volunteers, SNCC people, or Mississippi people, was that a lot of them were Emmett Till’s age when he was murdered. Five years later, they’re the ones who really started the movement. So let’s look at what the kids who were Trayvon and Renisha’s age do five or six years from now.

Kiese Laymon: When I watch and hear all your work, I feel extremely cared for, extremely loved as a black boy from Mississippi. I wonder if you could talk about how important this ethic of love is to your art.

Stanley Nelson: There’s this abiding love that has to be present in our work. It’s a real love of who we are and what we’ve been through. We have to recognize the love of where we’ve been a little more. But seriously, that’s one of the nicest things anyone has ever said to me. So thank you.