The Polish Boxer tells the story of Eduardo Halfon, a Guatemalan professor chasing after a Serbian pianist chasing after invisible Gypsies. The book may be a novel or a short story collection, a memoir or an artful lie. The real Eduardo Halfon—the author of the pages we read—is an engaged, obliging interview subject, but on certain topics he prefers to leave his interviewer, and his readers, a little disoriented.

Halfon says that he often thinks in English, but finds that by the time pen reaches paper the words are in Spanish. In The Polish Boxer, his characters are after a variety of this same alchemy, sending Gypsy hagiographies by postcard, sketching out the sensations of an orgasm, and generally dancing, drinking, or smoking themselves toward oblivion. Coursing through their stories is the tale of Halfon’s grandfather, who saved himself from Auschwitz with a lost incantation and told his grandchildren that a forearm tattoo was just a reminder of his telephone number. The resulting work is a sort of unruly parable, told by a restless narrator who savors the people and places that unsettle him most.

The Polish Boxer is the first of Halfon’s twelve works of fiction to be translated into English. The translation was performed by a team of five, together with Halfon himself, who speaks fluent, vibrant English. He is a Guggenheim Fellow, a winner of the José María de Pereda Short Novel Prize, and was named one of Latin America’s thirty-nine best young writers by the Hay Festival of Bogotá. On May 2nd and 3rd, he will appear in New York at the PEN World Voices Festival. His story “Bamboo” is currently featured on the PEN website.

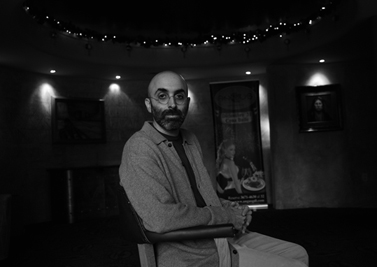

Halfon spoke with me by Skype from his home in Nebraska, where he now lives with his wife and the diabetic cats that occasionally visit from a local shelter. He takes obvious delight in conversation, leaning toward the screen from time to time, as though to better examine an idea or a turn of phrase. We spoke about his grandfather, his longing to be a musician, the art of ensemble translation, and the games he and his readers play. At some point during our conversation, a cat named Rocco nestled against Halfon, and the occasional stroke of Rocco’s white coat gave the author an air at once tender and sinister.

—Dwyer Murphy for Guernica

Guernica: You have a special interest in writers’ origin stories. In El Ángel Literario you imagined the moment of vocation for others—Nabokov, Carver, Hemingway. What’s yours?

Eduardo Halfon: It was accidental. I’m an engineer. I was never a writer, never a reader. The process of my finding literature had a lot to do with the frustration I was feeling in the time period after university. I had left Guatemala when I was ten years old, and spent almost twelve years in the U.S. When I finally finished my engineering degree, I had to go back to Guatemala. I didn’t have a choice. I had to go back to a country I didn’t know anymore, and to a language I barely spoke. I’d almost forgotten my Spanish—English had completely taken over, or almost completely. I had to go back to a profession that wasn’t really mine, to a family that was now alien to me. And that started a period of extreme frustration.

Guernica: The feeling of dislocation sparked your creativity?

Eduardo Halfon: I was what in Spanish we call desubicado, which is a word very difficult to translate into English. It means “not being situated”—in a profound way, not only in a physical way. And as the years went on, this sense of not belonging only kept getting worse. I was twenty-eight or twenty-nine when I decided to go back to university in Guatemala. I enrolled in a philosophy course, perhaps because I’m very rational and I thought philosophy would give me some kind of answer. But in Latin America, it’s a joint degree: Letras y Filosofía. If you want to study philosophy, you have to study literature. They forced me to take a literature course. And it was immediate—I immediately fell in love with reading fiction. Something about fiction, for some reason, at that moment in my life, just seduced me.

A number on my grandfather’s forearm was the beginning of The Polish Boxer: this one image in my head of growing up as a kid in Guatemala, and looking at my grandfather’s forearm, and him telling me it was his phone number.

I then decided to work only part-time as an engineer, and for about a year or two would read all afternoon. I just could not get enough fiction. Eventually, I quit my job completely and lived off my savings for a year. I just wanted to read. And a consequence of so much reading is writing. Writing is secondary. Writing is an afterthought of reading.

Guernica: Which writers were you reading in those early days?

Eduardo Halfon: Mostly North American writers, and most of them in the short story tradition. Maybe that’s why I constantly go back to that genre. I’m essentially a short story writer. That’s where I feel most comfortable, or least uncomfortable. My technique or approach in constructing a short story is very much based on the North American tradition, much more so than the Latin American one. I feel much closer to Hemingway and Carver and Cheever, for example, than I do to Borges and Cortázar and García Márquez.

Guernica: What were the origins of The Polish Boxer?

Eduardo Halfon: Usually, when I write, I start with an image, and then improvise from that image, riff around it. When I sit down I have no idea what I’m going to write. I just have images in my head. I just sit down and start playing with images through words and let those images go wherever they need to. I let the stories or the characters take me where they need to take me. I think of a novelist as having an extremely detailed blueprint of what they’re going to do for the next few years. I don’t have one, and if I think I do, I’m deluded. I just have images.

A number on my grandfather’s forearm was the beginning of The Polish Boxer: this one image in my head of growing up as a kid in Guatemala, and looking at my grandfather’s forearm, and him telling me it was his phone number.

Guernica: And how did you go from image to story?

Eduardo Halfon: I guess that that image—of a Holocaust tattoo as his phone number—later became a conversation. One rainy afternoon, I was drinking whiskey with my grandfather when he told me the true story behind that number, behind those five green digits. A very brief story that had to do with Auschwitz, and a twenty-dollar gold coin, and a boxer, and the saving power of words. He spoke for hours that afternoon, about many things that had happened to him. But that story about a boxer instantly crept under my skin.

Guernica: Did your grandfather approve of you telling his story?

Eduardo Halfon: I published El Boxeador Polaco in Spanish in 2008, and my grandfather died in 2009. My mother had read it out loud to him, she told me, as he cried. He became very sick at the end of his life. He was delirious. He couldn’t sleep. He thought there were German officers in his room, waiting for him. On the morning he finally died, I went into his room and saw him lying on his deathbed. And there, on his nightstand, was my book, his book, his story.

I think he was very proud of the book, or proud that his story would stay behind. By him not wanting to talk about it for so long, his legacy was going to be lost. So perhaps he felt a sense of pride, not only in his grandson the writer, but in leaving behind his story, his testimonial.

Guernica: Is there a place where you feel most comfortable? A country or a community?

Eduardo Halfon: No, I’ve yet to find a place where I feel comfortable. Not only a place physically—not Guatemala, not Spain, not Florida, not Nebraska—but not a profession either. I was an engineer by nature more than vocation. I write because that’s what I do. But I’ve yet to feel at home. And I think that comes across in my writing. I haven’t arrived anywhere.

Guernica: Do you find it easier to write about a place—Guatemala, for example—when you have some distance from it?

Eduardo Halfon: Yes. There needs to be not only a physical distance from what I’m writing about, but a temporal distance as well. My grandfather told me his story in 1998 and I finally wrote it in 2007.

To give you another example, the book I’m working on now—called Monastery—is set in Israel, and it grows out of The Polish Boxer. It’s a continuation of one of the chapters, or one of the characters. It’s about something that happened during my sister’s Orthodox wedding in Jerusalem almost twelve years ago. I revisited something that happened twelve years ago, or something that might have happened twelve years ago, and wrote about it.

Fiction needs time. It needs to settle. It needs to be ready. It’s not an immediate genre. You can’t rush a story. It took me years to write my grandfather’s story, years to write those ten pages about my grandfather and a Polish boxer. And not because I wasn’t trying. I kept making attempts to put his story on paper. But I couldn’t figure out how, couldn’t find the angle, couldn’t find the voice or the tone. The story wouldn’t let me in—it wasn’t ready, or I wasn’t ready. Until I realized that it wasn’t really a grandfather’s story that I wanted to tell: it was the story of a grandson as he receives his grandfather’s legacy, his family story. If you read it with that in mind, from that point of view, you’ll see that the camera keeps turning back to the grandson. It was his reaction that I was interested in. And once I figured that out—it took me years to figure that out—then I could write it.

Guernica: So you wrote the other chapters in The Polish Boxer before you wrote the central piece—your grandfather’s story?

Eduardo Halfon: Right. The book was still called The Polish Boxer, and my grandfather’s story would pop up here and there. I was carrying it with me, and so in every other story I wrote during that time, I would allude to my grandfather’s story, or say a little bit about it, but I was always afraid or hesitant to tell it. I thought I had finished the book, and I gave it to my Spanish publisher without that story, without the title track. And he said, “This is not complete.” He was absolutely right.

Guernica: Should The Polish Boxer be read as a novel or as a short story collection?

Eduardo Halfon: Whatever works best for you. I really enjoy that there are readers who will fight to the death defending this book as a short story collection. And there are the same number of readers who will fight to the death defending it as a novel. Or as a memoir. Or as autobiographical fiction. Or as nonfiction. That’s great. Wherever you want to classify it. In whichever bookshelf you want to stash it.

Guernica: Why do you think this was your first work to be translated into English?

Eduardo Halfon: The English language marketplace is not the most open one. It’s very hard for any international writer—Spanish, Japanese, Russian, Chinese—to get their work into English. There is very little room for all of us. We just don’t fit. In my case, although I was so close to the English language, it still took a long time to break through. A lot has to do with luck, I suppose. Some has to do with the type of books I write, with the type of book that The Polish Boxer is—a very literary book. It’s not extremely accessible. It lacks a defined genre. Its structure is unorthodox. So it had to find a very special publisher. And Erika Goldman, my publisher at Bellevue, just got it from the beginning.

Guernica: You’ve suggested previously that thoughts come to you in English, and then you translate them into Spanish prose. Is that still your writing process?

Eduardo Halfon: At the beginning it was much more so. English was much more present. I’m actually thinking in two languages now, straddling two languages. I write from this junction of Spanish and English. But somewhere between my head and the page those words turn into Spanish. I don’t know how this happens, or why. But there’s a translation process as I write.

Guernica: Why choose to write in Spanish? Does it feel like a choice at all?

Eduardo Halfon: It was never a choice, no. Or I don’t remember it that way. When I began writing, I just began in Spanish. Maybe because I was living back in Guatemala then, back in Spanish. Or maybe because Spanish was my first language. It was my childhood language, during my first ten years, before being thrown out into the world. And all writing, all art, is just a means to find our way back to our own paradise.

Guernica: Does the English translation of The Polish Boxer, as published, match up with that primordial story you first thought out in some mix of English and Spanish?

Eduardo Halfon: I was very much present during the translation. It was very bizarre, because I gave the translators—it was a group of five translators working together—my words in Spanish, most of which had been originally thought in English. And then they gave me back their version of my words, which did not necessarily concur with those original English words in my head. So I was reading someone else’s English. I soon learned, however, that the English in my head wasn’t the most literary, or the most beautiful, and had to learn to let go and trust my very talented translators.

Translation has to be a collaboration, especially when five translators are working together. They workshopped the book. It was a group of five friends and colleagues—six if you count me in—collaborating. There was this sense of working together to produce a musical piece. All instruments needed to be tuned. Everyone needed to play on the same beat.

As a writer, I’m giving each reader not the words he wants, but the words he deserves.

Guernica: Did you have a particular role in the collaboration?

Eduardo Halfon: I was very involved in the music of the language, the rhythm of the language. Not so much the words, but trying to achieve in English the same music or rhythm that I have in the Spanish version, which is very important in the book. The book should read lyrically. There should be a cadence to the words and the sentences—at times longer, at times shorter, at times staccato, at times more drawn out. That is intentional. I want to create in the reader a visceral effect, an emotional response.

Guernica: Are you imagining a specific type of reader when you write?

Eduardo Halfon: I am always writing for someone. I don’t have a specific reader in mind —not a certain age, not a certain nationality—but I’m thinking of a reader who wants to be taken somewhere by literature. To be challenged and transported by stories. That’s the power of language. In my grandfather’s case, it was a lack of language. He saved himself at Auschwitz by saying what a Polish boxer told him to say, and by not saying what he told him not to say. “But what did the boxer tell you? What words did you use to save your own life?” My grandfather didn’t remember, or he didn’t care. He just used them once and they were done. As a writer, I’m giving each reader not the words he wants, but the words he deserves. I do this explicitly in my stories—the code word that gets you into the Gypsy bar, for example. But there’s also the code word that gets you into the page. The magic word. It’s almost a childhood game: what’s the magic word that’s going to open this universe for me, that’s going to let me into this book?

Guernica: How else do you go about opening up that universe?

Eduardo Halfon: Music has that key. I wanted to be a pianist when I was younger. I’m a frustrated musician, can’t you tell? In my writing, there’s this very profound longing and desire for the music I can’t reach, for the music I can’t have. I’m drawn not only to stories about music, but to language as music. I listen to Monk or Parker, for instance, and I can’t describe it exactly, but I feel as though I’m being drawn into something mysterious, special, all-consuming. And when I find a book that does that, I can’t wait to wake up in the morning, to get to it again. That is the best feeling as a reader, isn’t it? When you get it. When you find it. And it’s not very common that you come across that special book, that special writer.

I’m trying to impose a disorder. I’m trying to have the reader feel the disorder that I feel—to feel the beautifully constructed chaos I feel with jazz.

Guernica: Are there subjects other than music that inspire that same longing?

Eduardo Halfon: The defiant search for roots is another. You see that in The Polish Boxer. These lost, nomadic characters all seem to be stubbornly searching for something they can’t quite reach—the scholar who teaches through humor, the classical pianist who only wants to be a Gypsy pianist, the engineer who wants to be a writer. There’s a common theme there. They all seem to be looking for something more profound and more intimate. But also, for all of them, reason is not enough—there’s something else. Ultimately, we don’t have the answers. I don’t have the answers. The writer is not the authority on anything.

Guernica: You’re not fighting an urge to impose order on your stories?

Eduardo Halfon: I’m trying to impose a disorder. I’m trying to have the reader feel the disorder that I feel—to feel the beautifully constructed chaos I feel with jazz, for instance. I don’t want the reader to be searching for an answer. There are more questions when you finish my book than there are questions answered, I think. There are all these loose ends that never really tie up. I don’t wrap it up in a nice little bundle. Life isn’t ever wrapped up in a nice little bundle.

Guernica: Do you use Eduardo Halfon—yourself—as a narrator for that same reason?

Eduardo Halfon: There’s a game that I like playing—blurring all types of preconceptions or genres or borders between what’s real and what isn’t. I’m lulling the reader—lulling myself, even—into not knowing what’s real anymore. Similar to achieving a hypnotic state, I suppose, while writing, while reading. You’re just in. You don’t doubt anymore. It’s all true, though you know it’s not all real. I’m usually asked why I do that. Why isn’t it just a differently named version of me, a thinly disguised narrator? I do it because I want to create an emotional response in the reader, and part of the way in which I do that is by drawing him into a comfort zone, into a more real experience. Then there can be a reaction to the book as though it were not fiction. Readers can completely erase the line between the narrator and myself. They absolutely believe—or should believe—that the narrator is me. And he’s not. Yet he is.

Guernica: Blurring that line—does it cause problems in your personal life?

Eduardo Halfon: Absolutely. My wife is jealous of Lía, my narrator’s girlfriend. Lía doesn’t exist. She exists only in fiction. Yet she’s very real.

Guernica: Lía is well served in the bedroom by Halfon. It doesn’t hurt to get some good buzz out there about yourself.

Eduardo Halfon: The narrator Halfon also smokes a lot. I don’t smoke. He seems to smoke like a fiend. He’s also all about sex. He also just seems to go off everywhere. He’s off to Serbia, off to Israel, off to Poland. He just isn’t as afraid as I would be, as I am. I overthink everything.

Guernica: You say he “seems” to do this or that—is he so liberated?

Eduardo Halfon: He’s got his own voice, which isn’t my voice. He’s got his own concerns, which aren’t necessarily mine. He’s very intrepid. I’m much more cowardly and rational and neurotic. By now he usually dictates his own actions. And a writer is like a proud parent when any of his characters outgrow him, and set off on their own, and get into some literary mischief.

Guernica: He’s quick to leave his job behind and go off on an adventure. What about you? Do you stick to a routine when you’re writing or can you manage it anywhere?

Eduardo Halfon: I have a very strict routine. I work every day. I work only in the mornings. I can only work at home. So when I’m traveling, whether it be to visit family in Guatemala or to give a reading in Philadelphia or New York, work just stops. But when I’m at home (and right now that happens to be Nebraska), I’m very strict with my routine. I read early in the morning, every morning, for a few hours. Then, at 9:30 a.m., I start grinding the coffee beans, and something about the sound of the grinding or the smell of the coffee takes me to my writing. And I work. But I can’t work if there’s anyone else around. I need the silence of the house. So everyone must leave the house. Everyone. Except, of course, my cat, Rocco, who always supervises what I’m writing.

Guernica: What projects is Rocco supervising at the moment?

Eduardo Halfon: Monastery, the short novel set in Israel, is finished and being published this year in Spain, next year in France. Now I’m starting to tinker with a Polish trip. Which is very unsettling. I went to Poland—Warsaw, Auschwitz, Block 11 in Auschwitz where my grandfather was held. I visited his hometown of Lodz, and found his home, which is still there. And then I came back and that was it. That was the trip. But to go from trip to fiction is not an easy bridge to cross. That could take ten years, or it could take ten days, or it could just falter. There is no plan to what I’m going to do next. There are only ideas. Only images like flashes of light. I never know what’s going to happen until it does.

To contact Guernica or Eduardo Halfon, please write here