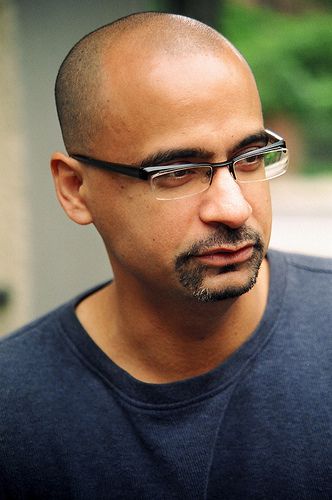

“We were on our way to the colmado for an errand, a beer for my tîo, when Rafa stood still and tilted his head, as if listening to a message I couldn’t hear, something beamed in from afar,” says Junot Diaz’s character, Yunior, to start the first sentence of the first story in Drown, the first book Diaz ever wrote. Since then, both the writer and his main character have gone on to garner a cult following across two subsequent works of fiction, the novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao and the recent short story collection This Is How You Lose Her. And though Drown’s first story, “Ysrael,” culminates with an unforgettably gory scene–a boy whose face has been mutilated by a wild pig is demasked in front of Yunior when his brother Rafa cracks a bottle over the boy’s head–that might have been lifted from the pages of a Stephen King story, it’s been rare, even among the flurry of attention surrounding Diaz’s latest book, for his fiction to be linked with a genre that has profoundly influenced him.

Until now. Fresh off the heels of This Is How You Lose Her, Diaz is openly at work on an alien epic, Monstro. In this interview, radio host Richard Wolinsky hones in on the ways in which science-fiction by the likes of Tolkein, Delaney, and Le Guin have helped Diaz to create a single character capable of conveying race, masculinity, and cultural displacement alongside nerdish preoccupations and misbegotten love affairs. “He’s a deceptive cat,” says Diaz of Yunior, the fictive figure who continually vacillates between the East Coast and the Dominican Republic, between languages, and toward the revelation that narrator and author are not necessarily distinct. “You realize that as one writer you can never capture your world,” Diaz says, though he notes: “Each book is an attempt to get closer, closer and closer and closer to that reality.”

Richard Wolinsky: I want to start by asking a little bit about your character, Yunior, because he appears in virtually every story, he appears in the novel, and he has your history, but he isn’t you. I would hope?

Junot Díaz: No, no. He’s not.

Richard Wolinsky: How many stories had you written before Yunior came along? Or was he there from the start?

Junot Díaz: I had an idea for Yunior at the beginning. My entire project had certain preoccupations. I kept looking for a protagonist that would allow me to address some of these preoccupations. I wanted to talk about gender. I wanted to talk about masculinity. I wanted to talk about race. I needed a character who was fantastically honest, fantastically observant. I also knew that if I was going to make him these things I needed him to be remarkably flawed and self-deceiving. I think I wrote for at least a few years before I stumbled on the perfect combination that would cohere around this character called Yunior. I think it was three or four years where I was dreaming of him but didn’t get him right. It wasn’t until about 1994 that I wrote my first story with him.

Richard Wolinsky: And was the voice then fully formed?

Junot Díaz: No, again Yunior’s voice has been a work in progress. This is what happens when you’re writing over a long period of time. Few of us are perfect and capture things right at the beginning. I think that Yunior finally hit his stride in The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. But he wasn’t half bad even in my first book Drown.

Richard Wolinsky: He’s got a very distinct voice, and it’s a voice that’s informed by your own reading, particularly science fiction and fantasy, which means you go back and read that stuff. You said you’ve lost count of the times you’ve read Lord of the Rings.

Junot Díaz: Yeah, I’ve certainly lost count. Without question I’ve read it once a year since I was nine. Plus throw in a few more dozen here and there. Whenever I feel real depressed, you go back to books that gave you great comfort and great information, and that’s the case.

I had gone from a 1970s Third World and then suddenly moved to New Jersey. It was as if you had gone in a time machine. It was extraordinary. The U.S., to a kid like me, felt like science fiction.

You know, I grew up in a time where a lot of the libraries still had the golden age of science fiction on their shelves. I group them by ABC. I grew up with Asimov. I grew up with Bradbury slash Bova. I grew up with Clark. Of course, go over to H and Z, we’ve got Heinlein and Zelazny. And then there’s the final D which is Delany. I grew up surrounded by that stuff.

Richard Wolinsky: There aren’t that many people of Hispanic origin writing science fiction.

Junot Díaz: No. This is an area that’s growing the hell up. You see a lot more new writers of color, a lot more writers of U.S.-Latino descent, but as a kid science fiction made perfect sense to someone like me who had lived such extreme reality. I had gone from a 1970s Third World – we’re not talking about a 2012 Third World – a 1970s Third World and then suddenly moved to New Jersey. It was as if you had gone in a time machine. It was extraordinary. The U.S. to a kid like me felt like science fiction. For a kid like me who grew up in the shadow of dictatorship, American realistic fiction or realistic stories, and their sitcoms, didn’t have any traces of the world I left behind. In science fiction and fantasy I saw a lot of myself reflected.

Richard Wolinsky: You say in Oscar Wao and you’ve actually said in an interview, that Trujillo was like Morgoth from Lord of the Rings. Or worse.

Junot Díaz: Sure, he’s our dark lord, a shadow that extends through time and that haunts the very people he afflicted.

Richard Wolinsky:: And then Balaguer is a kind of Sauron?

Junot Díaz: Yeah, or a minor demon. I always call him the election thief. But these two characters, man: the Dominican Republic certainly could have done worse, but not by much.

Richard Wolinsky:: There’s one story in This Is How You Lose Her which is about Yunior and his brother and family first coming to New Jersey and dealing with snow. Is that autobiographical?

If Yunior’s New Testament, Rafa is Old Testament. Rafa’s the guy who comes through your house and takes your eye out because you tried to punch him in the face.

Junot Díaz: I think the physical elements of it are. I think my experience is very, very different. We weren’t locked in. We weren’t on house arrest. I also had two sisters, and their experience really added to ours. The memory of the cold and the memory of the neighborhood, I drew upon. But these particulars of Yunior’s experience, with his crazy father and being locked in the house, were invented.

Richard Wolinsky: The brother, Rafa, is he still alive now?

Junot Díaz: Yes, I have a brother who is completely different from this brother. The brother in the book is sort of a satanic extremity of my brother. He’s completely, completely different. When I was arranging and creating Rafa I always kept saying if Yunior’s New Testament, Rafa is Old Testament. Rafa’s the guy who comes through your house and takes your eye out because you tried to punch him in the face. I don’t think Yunior lives in that reality.

Richard Wolinsky: And they’re both very much into body building, particularly Yunior after Rafa dies. Were you into body building too?

Junot Díaz: I lifted weights for a very long time. Yunior’s the kind of guy–again I abstract from my experience and put it on to Yunior–I enjoy the thought of how much Yunior attempts to hide his vulnerabilities, encasing it behind all this flesh. Whereas the brother doesn’t seem to be particularly aware of vulnerability. The brother throws himself on the point of a knife any chance he gets, but Yunior lives most of the time terrified.

Richard Wolinsky: In all of these stories did you ever work out any timeline about their lives?

Junot Díaz: Of course. You always have to leave room for the fact that there’s more than you can ever recount. Any recollection of your life is by it’s nature incomplete, and so I leave room for it to breathe. I leave holes. But certainly–I filled a whole darn notebook sketching out which way this family was going and which way Yunior was going till about his fortieth birthday.

Most people don’t naturally put a Toni Morrison next to a William Gibson, but I could never have become a writer if these two books hadn’t been next to me on my shelves.

Richard Wolinsky: So in the last story in the book, “Cheaters Guide To Love,” is that Lola from Oscar Wao?

Junot Díaz: In the last story of the book, it is implied that it has something to do with Lola. But I’ll tell you what, there’s a story, “Miss Lora,” in the book, with the girlfriend that he meets at Rutgers, who has his head shaved, and is a mujerón, that is Lola.

Richard Wolinsky: Let’s go back a little bit. You grew up in this environment and you read a lot. Were you always thinking about being a writer?

Junot Díaz: No. I always wanted to read. I always thought I was going to be a historian. I would go to school and study history and then end up in law school, once, you know, I ran out of loot trying to be a history high school teacher. But my dream was always to place myself in a situation where I was always surrounded by books.

Richard Wolinsky: Yunior goes to college late. He starts when he’s in his twenties. Did you start right after high school or did you wait as well?

Junot Díaz: No, I started immediately after high school. I was in one of these situations where my mom was like, “Either you’re taking college classes, even though you’re working full time, or you can live on the street.” And it was a smart thing for her to do. Because if I hadn’t been kept busy, I would have definitely just lost my way. I was one of those kids who, I gotta tell you, man, I was not one of the smartest kids growing up. But who is?

Richard Wolinsky: But you went you went off to college, and were you writing in college then?

Junot Díaz: Well, my first year I went to one of these kind of small state schools, a commuter’s college. I wasn’t writing then, I was just working. Hustling, classes, delivering pool tables, chasing girls the way we did at that age. It was only when I went to Rutgers that I began to discover a totally different world of literature with the power to transform lives, literature with the power to intervene in larger questions of society. And I have to say, before that I’d never really appreciated how profoundly powerful literature could be. It wasn’t until that experience at Rutgers College, that I began to take seriously my love of books, my love of storytelling, my love of narrative and think, “Hey, this might be something that I could do.”

Richard Wolinsky: Well, around that time, I know when I was in college, I probably read the same books you did. Then after that I kind of moved away from science fiction and fantasy and expanded outward and semi sort of stopped looking back. But you kept reading it too.

Junot Díaz: No question. Listen, I always put Toni Morrison, Sandra Cisneros, Leslie Marmon Silko, Maxine Hong Kingston, my most important university authors, with William Gibson. William Gibson struck me at the same damn time. Neuromancer had basically come out a few years before I went to college, and when I went to college it was all the rage among the hip little nerd kids. And it struck me: Gibson, not only as a sort of social critic, not only as a stylist, not only as a superb artist, was really, really important to me. He was such a great, smart progressive. And he lived in this world! Most people don’t naturally put a Toni Morrison next to a William Gibson, but I could never have become a writer if these two books hadn’t been next to me on my shelves.

Richard Wolinsky: What prompted you to write then realistic fiction, rather than go directly into science fiction, particularly because people like Octavia Butler were using science fiction, and Chip Delany were using science fiction, in the social context? And Le Guin as well.

Junot Díaz: Well, I can’t speak for any of those three, but they seem to come out of traditions where there had been an enormous body of work about the reality that they’d come out of. Even Samuel R. Delany, Butler, Ursula Le Guin–we already had dozens of books about the African American experience, about the African American experience at Harlem, about the woman’s feminist/intellectual experience. So I think that in some ways there was a certain amount of freedom. Now I’m just sort of thinking aloud.

I don’t think my book is any more political or any less political than, say, a mainstream novel.

Whereas, I come at a time where the Dominican diasporic experience was completely non-present. It had been almost barely narrativized. And I felt like my Middle Earth, the world that I was going to retrieve, the world that I was going to create, was this world that no one had ever ever encountered, that no one had ever voyaged to. All the skills that I learned in science fiction and fantasy for world building, I brought to bear in building the world of Yunior de la Casa’s family. Building the world of the Dominican Republic in the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s, ’80s, ’90s, and 2000. And in many ways, I feel that no more is Dahlgren a constructed world than The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.

Richard Wolinsky: In reading Oscar Wao, I noticed that the footnotes take Trujillo and the Dominican Republic and put it into this science fiction construct, so that in a sense, we are walking into an alien world.

Junot Díaz: No question. And we are taking a world that some Dominicans think they know, and we’re making it alien. We’re estranging them from it. Plenty of Dominicans who read this book are not used to thinking of Trujillo as a Sauron. It destabilizes our definitions. Many who are familiar with Sauron are not used to it being linked to a twentieth century Caribbean dictator. I think that it’s a helpful conversation. A helpful cross pollination.

Richard Wolinsky: The historical material in those footnotes–those are all real? That’s all research?

Junot Díaz: Oh I would be very, very cautious of heeding those footnotes. They’re not historical dissertations. We must remember that in the book, Yunior keeps flagging his unreliability. Yunior keeps flagging that he’s lying and making stuff up. He’s like, “Oh, yeah, remember that last footnote? Yeah, that didn’t really happen then, I just did it because I liked it.” As soon as you meet someone who’s that cavalier with information, I would beg you, I would exhort you to be cautious.

Richard Wolinsky: Is Yunior as unreliable in This Is How You Lose Her as in Oscar Wao?

Junot Díaz: I think that Yunior’s difficulty with revealing who he really is is not just a matter of his character world it’s also a matter of his relationship with anyone reading him. Because in all three books, Yunior is the persona that is writing the books. And the actual reader is encountering Yunior’s persona even as they’re reading. Yunior is asking them to play games, to believe him or not to believe him. I think in the game of This Is How You Lose Her, the question of whether Yunior has changed or is reliable are fundamental questions for a reader.

I think Yunior is incredibly honest about how he sees reality. Part of what makes a reader squirm is how he will describe things as if he is an alien.

Richard Wolinsky: I want to go into some of the other issues that you were talking about, the political and gender issues, but I noticed in Oscar Wao that it took awhile for me, not having read Drown, to understand that Yunior was writing the whole book.

Junot Díaz: Yeah, he’s a deceptive cat that way. Listen, Yunior’s ability to mask his hand has been an important part of my project. Most people read This Is How You Lose Her and don’t make immediately the connection of the one story that feels like it’s not about Yunior–don’t make the direct connection that this is Yunior writing about the other woman because Ramon is his father. The woman writing in Santo Domingo, her name is Virta, that’s Yunior’s mother. Yunior in Drown mentions that his mother lost children before he and his brother were born. You would have to be a super, super nerd and have to have Drown coming out of your ears to make those connections. But this is the way Yunior likes to play. I’ve always enjoyed that about him. I think of him, of his writerliness, as much a character as the character we meet on the page.

Richard Wolinsky: When you were writing Yunior’s perspective, how conscious is the manipulation?

Junot Díaz: Very conscious. I always ask myself when I’m writing a book, especially since Drown, what is the trick Yunior wants to play on the reader?

Richard Wolinsky: Really?

Junot Díaz: Of course! Because that’s Yunior’s gift–his ability to lure readers into a labyrinth, herd them into a house of mirrors. In Oscar Wao, I knew what the trick was–that Yunior reveals himself to be that narrator but also that Yunior is hiding what a dictator he is in this book. Second of all, what is the trick that Yunior plays in This Is How You Lose Her? It’s that the book we are reading is not directly from me. It’s Yunior De La Casa’s book. He, at the end of the book, is seen writing the book that now we realize that we have been reading. And the question is now, how much of this book is Yunior trying to convince us of something and do we believe what he is attempting to convince us of? And again, most people don’t care. But for big time nerdy grad students this stuff is embedded so that they can pick over it.

Richard Wolinsky: It also means that when he is talking about what a bastard he is, the question is does he really think he’s a bastard or is he lying to us?

Junot Díaz: No, I think he thinks it. This book would be a hard book to read and not feel palpably his regret and his recognition of what he’s done wrong. We can say anything we want about this character but unlike most of us who do bad stuff and don’t want to look back over our shoulder, Yunior hovers over his crimes, and he’s a very different character for that.

Richard Wolinsky: In bringing in the Dominican-American experience, as an immigrant and as a Hispanic in the United States, how conscious are you of bringing in political ideas?

Junot Díaz: I think no more that say a John Updike or a Jonathan Lethem or a Rick Moody. I think that most of us are aware that as writers we are seeking absences, we’re seeking silences, we’re seeking spaces that people haven’t entered. No writer is saying, “Hey, I want to go to this very well trod territory and say exactly what someone else has done.” I think the nature of a writer, because we are attempting to bring to light areas that people haven’t seen before, tends in some ways to be progressive, at least in that light. I don’t think my book is any more political or any less political than, say, a mainstream novel. It’s just that our politics are recognized in different ways. If you’re a status quo writer, you’re considered to not be political but that’s as political as if you’re a progressive writer. Some politics are asked to show their passports and others aren’t. In this country, if you’re slightly progressive, people have a lot of suspicions that you’re up to some sort of conspiracy, that this is some sort of plot. On the other hand, if you’re conservative and mainstream, people tend to take that as a given and don’t notice the politics. So I guess I’m no more and no less aware than your average writer I assume.

Richard Wolinsky: From what I know from mystery writers, they’re hyper-aware.

Junot Díaz: Mystery writers are among the coolest of the cool. Because they can get away with doing wild stuff that very few mainstream writers can do.

Richard Wolinsky: And using the voice of Yunior, you’re creating a kind of kaleidoscope of his relationships with women. Now we assume reading the book that he is being honest and these women exist but they may not even exist.

Junot Díaz: Well, I don’t think we want to go to the “it was all a dream” Dallas thing–

Richard Wolinsky: No, no, I was just thinking it was all made up by Yunior to illustrate a point.

Junot Díaz: I highly doubt that. I mean, the one thing about Yunior again–I’m talking for my character here and I take it for granted–but I don’t think Yunior’s problem is that he’s a dishonest chronicler of reality. I think Yunior is incredibly honest about how he sees reality. Part of what makes a reader, if they read this book, squirm, is how he will describe things as if he is an alien. As if he doesn’t know that this is embarrassing, that he doesn’t know that this is going to be shameful. He says a lot of things that on the surface one would have to say it couldn’t be anything but the truth.

Richard Wolinsky: Well I walk away from it going–and again I don’t know if this is all men or just Dominican men–the men are bastards and the women are right to leave them.

In the movie Lord of the Rings, Gandalf gets played like Santa Claus. In the books of Lord of the Rings, Gandalf is a sharp, touchy, bristly, proud old man who isn’t there to give anybody a space hug. And I prefer him.

Junot Díaz: Well, I would say as goes one group of men goes all men. Rare is the culture that is immune to any of the stuff that’s happening to these characters. I feel like the only reason I have readers is because women from all sorts of cultures and all sorts of backgrounds read these characters, or at least the readers I do have, they see themselves, they see their men, they see their women, in these characters from this tiny little island in this tiny little state called New Jersey. They see them reflected in these people. All my queer and gay friends feel like, “Wow, where’s our lives?” You realize that as one writer you can never capture your world. Each book is an attempt to get closer, closer and closer and closer to that reality.

Richard Wolinsky: It seems like This is How You Lose Her would be getting closer to the lives of Latinas, of women in particular.

Junot Díaz: There’s that, and that moment. I always think this is the book. Oscar Wao was about these larger national, these larger profound, ancestral questions. This is a book that really, really focuses. It drills down on the daily quotidian demands of intimacy. Every time Yunior gets close to being vulnerable, Yunior does something to destroy it.

Richard Wolinsky: What was the purpose of putting a couple of the stories in second-person?

Junot Díaz: Second-person is a way to get some distance. It’s a really interesting form because it allows for a certain cooling down. Not everybody likes it, but for me the only way these stories worked—and again I tried these stories for years and years—and the only way they came together was when I finally created a certain kind of cool, collected space between the reader and the work.

Richard Wolinsky: I understand you’re working on this giant epic called Monstro. Is that correct?

Junot Díaz: Yeah. I don’t know if it’s giant, and I don’t know if it’s an epic, but I’m certainly working on an alien invasion, virus, giant monsters eat Haiti and Dominican Republic novel. I don’t know if I’ll ever finish it.

Richard Wolinsky: Do you plan to continue writing about Yunior then?

Junot Díaz: No. This book is a bit of science fiction, science horror. I’ll see where it takes me.

Richard Wolinsky: How do you feel about moving into genre? How do you think it’s going to be accepted, or don’t you care?

Junot Díaz: What do I know? There’s stuff you can control and for me the only thing I can control is whether I can write this book. Even that I don’t think I have a great amount of control over, because sometimes books die on the vine.

Richard Wolinsky: How far into it are you?

Junot Díaz: Not far enough.

Richard Wolinsky: I read somewhere that the protagonist is a fourteen-year-old girl?

Junot Díaz: Yes. The protagonist is a fourteen-year-old girl who is, at the moment, obsessed with a Spanish mace-weapon in the weapon museum in the Dominican Republic, which she will use to bash monster’s heads in.

Richard Wolinsky: What do you think of movies like Avatar?

Junot Díaz: What can one say? It’s the greatest money-making Pocahontas story ever told. Technically, it’s wow, wow, wow, wow, wow, wonderful. But at the level of narrative it’s A, B, C. Yet people dug it, so what can I say? I’m not here to bash what people are vulnerable to. People are vulnerable to that old story of white man comes to a new world, falls in love with alien princess, saves planet, yay.

Richard Wolinsky: And the film versions of Lord of the Rings?

Junot Díaz: I enjoyed them. I don’t think they were very accurate, and I don’t mean accurate just from the point of view of events. They were inaccurate to the core of the characters. Because in the movie Lord of the Rings, Gandalf gets played like Santa Claus. In the books of Lord of the Rings, Gandalf is a sharp, touchy, bristly, proud old man who isn’t there to give anybody a space hug. And I prefer him and I prefer the Aragorn of the books, where Aragorn is a battered veteran in ways that even Viggo Mortensen—who I adore and I think did a wonderful job—I don’t think he was given the role that he should have been given. I think had he been allowed to play the Aragorn of Lord of the Rings, he would have knocked it out of the park.

Richard Wolinsky: Do you still read new science fiction?

Junot Díaz: Of course, of course, of course. I love Nalo Hopkinson. She’s absolutely wonderful. I adore her.

Richard Wolinsky: Jamaican woman writing science fiction.

Junot Díaz: I know, see? Yeah. I love Tobias Buckell. He’s new. He’s great. He’s got a couple books out—really, really smarty-pants. And then of course the people who are the colossuses like Vernor Vinge, I’m still reading.

Richard Wolinsky: What happened when you found out you won the Pulitzer?

Junot Díaz: What do you always do when you find out that you win something, and your mind can’t grasp that your life is about to change? I know what I did. I sat down and just spent about twenty minutes in shock and then the phone calls came in and the next day I got up and got to work.

Richard Wolinsky: You didn’t feel any pressure for this book?

Junot Díaz: No. I always say this, but it’s true. I feel so much pressure regardless of what the outer world is bringing. I carry around on me, on my back, a Himalaya. So who cares if you decide to add a pound of sugar on top of that. I can’t feel it. You could put a Pulitzer on a Himalaya and I wouldn’t notice the difference.

Richard Wolinsky: What are you working on now in addition to the epic?

Junot Díaz: Nothing. My little girl, I’ve got to get her up and killing eighty foot giants.

Richard Wolinsky: One final question: what do you think attracts Dominicans to New Jersey?

Junot Díaz: What attracts immigrants everywhere to a place—it’s always the jobs and the people who came before. My family immigrated to New Jersey right during the whole collapse of the manufacturing industries in New York, they were just bottoming out, and there were plenty of companies up and running in New Jersey and people moved to those jobs.

Richard Wolinsky: As with Yunior’s family, did you move around a lot?

Junot Díaz: No, I never moved around, I moved once. I lived in the same two houses for the first twenty-four years of my life.

Richard Wolinsky: You’ve lived in Boston, and there’s a story that takes place in Boston with Yunior as a professor with a bad back.

Junot Díaz: And with a real paranoid sort of sense of victimization, he’s kind of nuts in that story.

Richard Wolinsky: Now that you’ve completed this, do you think about writing stories from different perspectives?

Junot Díaz: I’m going to write a story about a twelve-year-old girl killing skyscraper-sized monsters, so I’m hoping that’s a different perspective.

“Bookwaves with Richard Wolinsky” originates in the studios of KPFA-FM Pacifica Radio (www.kpfa.org) in Berkeley, California and can also be heard at other radio stations via Pacifica Audioport syndication.