The script was for a film called Who We Are, a drama set at Russell College, the small liberal arts school in northern New York where Sam had matriculated. The partly autobiographical story had been his senior thesis. Central to the design of the work was the way it compacted time, by means of a trope that Sam privately considered so ingenious he sometimes broke into cackles just thinking about it.

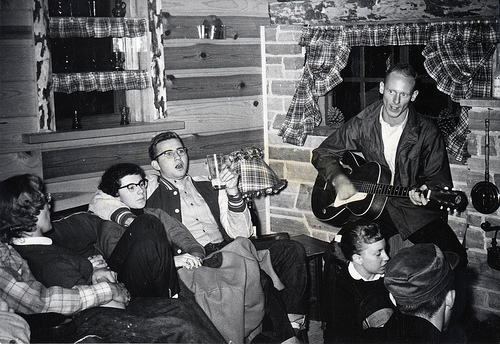

At the break of day, the narrative’s half-dozen or so main figures are callow eighteen-year-old freshman, but as the film advances—through parties and drugged-out drum circles, couplings and arguments and pranks—they age at a super-accelerated rate, encapsulating all four years of college in a single May Festival, the annual daylong bacchanalia that was the inebriated topper on every red-blooded Russell undergraduate’s year. At sunup of the following morning, finally partied-out, the characters are grown-up seniors on the verge of graduation, with different haircuts and thinner faces and better clothes, yet in every significant way no more prepared for the real world than when they started.

While most readers of Who We Are found it funny in places, it was an essentially lyric piece that Sam felt spoke to the mad, arrested quality of those four years and, in general, of what a desperate thing it was to be young and free and American.

…Roger has become so chronically dubious by the film’s latter stages that he refuses to believe his own mother when she calls, sobbing, to inform him that his father has suffered a fatal aneurysm. “Nice try,” he says and hangs up on her.

One character, Rachel, is a button-downed, suburban honor student when we meet her in the morning; when we leave her, four years later, she is a fully committed member of an eco-terrorist cell; through the first quarter of the movie, Hugh drinks beer after beer, backslaps everyone in sight, climbs on every available chair and tabletop to make ribald acclamations to his friends; by the last fifteen minutes or so, Hugh has stopped going out altogether, developed a policy of conducting communication exclusively via the Internet or speakerphone, become too indolent to even bother dressing himself, and just lies on his couch, gloating aloud about the energy that his old companions are wasting while he is relaxing; another, Florence, renames herself Diana, and then Aurora, and then Divinity, before finally going back to Florence—the bright, gifted arts major who woke up that morning gradually transforming into a grim scold, her final project an installation of a dumpster filled with words carved from piss-soaked foam blocks: EMPATHY, TRUTH, INTEGRITY, and so on; a gold-chain-wearing high school football star when we meet him, Brunson discovers his homosexuality during the first twenty minutes of the film, begins to treat his shame and anxiety with crystal meth around the forty-minute mark, and shortly afterward disappears completely right in the middle of a scene, at which point everyone else ceases to refer to him except in the past tense; Kira spends the entire movie holding hands, only the person with whom she’s holding hands keeps changing, and they’re always arguing about that other person’s lack of faithfulness; she becomes angrier and angrier, until she literally bites her last lover, ripping a chunk of flesh from his cheek.

In a typical scene about midway through, Roger, the ostensible leader of the group, abruptly breaks up with his girlfriend. Initially a humorous skeptic, Roger has become so chronically dubious by the film’s latter stages that he refuses to believe his own mother when she calls, sobbing, to inform him that his father has suffered a fatal aneurysm. “Nice try,” he says and hangs up on her.

Several of the screenplay’s characters were modeled on real people: Roger, for instance, was Sam’s stand-in, and most of the things that happened to Roger—like the phone call scene—were semi-fictionalized versions of events from Sam’s own life. Another key player, Hugh, was plainly based on Sam’s best friend, Wesley Latsch, who had in reality, over time, winnowed his direct human contact to the bare minimum and become so resolute in his fecklessness that there was a kind of integrity to it. Claire, Roger’s girlfriend, was a dead ringer for Sam’s actual college girlfriend, an indefatigably good-natured young woman named Polly Dressler:

EXT. NORTH FIELD PARKING LOT – MID-AFTERNOON

The group comes to Roger’s Saab. Behind them, in the meadow and on the hillside, the festival continues—people jumping up and down in the bouncy castle, a juggler with devil sticks, the rotating Ferris wheel, etc.

Slurpee-time!

T-minus Slurpee!

Roger unlocks the car with a CLICK, as Claire pulls on the passenger-side door with a CLACK. Claire has pulled the handle too soon.

Roger opens his door and climbs in. Claire pulls again on the handle of the passenger-side door, to no avail. Hugh stands with her.

Roger stares at Claire through the dirty glass. Roger’s Radiohead t-shirt is now a Wilco t-shirt. Claire’s glasses are gone and her hair is different.

BACK-AND-FORTH, THROUGH THE PASSENGER WINDOW:

Let me in! I want Slurpee!

Slurpee motherfucker!

No. It’s over. I can’t do this anymore, Claire.

What?

I can’t be with you. You’re a handle-puller.

What?

I’m sorry, but we’re through.

Why are you being such a jerk? I just want to get a Slurpee and have a fun day.

I could never love a handle-puller. I mean, it’s proof that we don’t fit.

Are you serious? This is not funny, Roger.

It’s not that you’re impatient, it’s that you want more from life than me. You want to get going. You want your Slurpee right away. You’re a handle-puller, Claire. You pulled.

Yes, but I didn’t mean to!

It’s too late.

She starts to cry, and gives Roger the finger.

(To Claire) No Slurpee for you.

Hugh raps on the window, and Roger lets him in. They pull away a moment later, abandoning Claire in the parking lot.

A Volvo pulls into the empty space. Bertie, the Welsh exchange student, climbs out, unloads his guitar. Claire, in fresh make-up now, face completely dry, runs over and leaps into his arms.

But it was true that Polly was a handle-puller. This fact was important to Sam.

In truth, Polly had dumped Sam. And she was the one who pointed out that their ambitions weren’t especially compatible. Polly wanted to have a career and a family and a house and lots of affairs with men whose discretion she could trust. Sam’s only real ambition was to make a movie. Beyond that, he conceded that he didn’t have much in mind for the future.

But it was true that Polly was a handle-puller. This fact was important to Sam.

The breakup had also taken about two years, which was the beauty of the conceit: the compression of such a development brought it into greater relief. What Sam meant to convey was that minor troubles and lingering dissatisfactions—say, one man’s deep-rooted irritation at his girlfriend’s blithe impatience toward car-door locking mechanisms—often added up to personal shifts with massive consequences.

Taken as a whole, no one who read the screenplay for Who We Are denied that it was clever in its composition, original in its pattern, and ruthlessly unsentimental in its conclusions. It was also “a bit portentous,” according to Sam’s father, Booth Dolan, the B-movie mainstay famous for his stentorian, blink-free performances in such films as New Roman Empire, Hellhole, Hard Mommies, Hellhole 2: Wake the Devil, Black Soul Riders, and Hellhole 3: Endless Hell, who, without invitation, had fished a copy of the script from Sam’s laptop bag.

Booth Dolan’s particular, gassy flair had spiced clunkers from virtually every genre with bathos: horror, western, blaxploitation, sexploitation, sci-fi, fantasy, animation, and any combination thereof. A daylong retrospective could begin with the Nixon-era paranoia of New Roman Empire (1971); continue on to Black Soul Riders (1972), in which Booth had played a racist judge named George Washington Cream and adopted a chicken-fried Southern accent to say things like, “Wuhl yer an awl-ful buh-lack wan, ain’cha?”; followed by Rat Fiend! (1975), infamous for its utilization of miniature sets in order to make normal rats look gigantic, and featuring Booth’s performance as a grizzled “sewer captain” with a “sword-plunger”; going next to Hard Mommies (1976), wherein Booth’s car-wash mafia messes with the wrong group of PTA moms in belly-baring tank-tops; and, as the main feature, Devil of the Acropolis (1977), arguably the crowning example of Sam’s father’s artistic offenses, for his portrayal of Plato as an expert in werewolf behavior (as well as a howling example of Hollywood’s regard for historical accuracy: Plato is killed by the werewolf in the 2nd act); and put a bow on the day with the first episode in the Hellhole trilogy (1983), the title of which said everything a person needed to know, except maybe that Booth’s character, Professor Graham Hawking Gould, was a “satanologist.”

To this day, on the highest movie channels, the ones that are all gore and tits and robots, a black-haired Booth can still be found battling evil with a plunger.

Even such a condensed list of Booth Dolan’s inanities threatened his son with the promise of a crushing migraine. The idea of a two-day retrospective, meanwhile—including such milestones as his father’s voice-over turn as Dog, an all-knowing talking cloud, in what had to be the nadir of druggy cinema, Buffalo Roam, about a Nam vet leading a white buffalo to the Pacific Ocean; as well as Booth’s role as an amiable, ass-squeezing brothel owner and leader of cowboy prostitutes in Alamo II: Return to the Alamo: Daughters of Texas—held lethal implications. Sam would rather have killed himself, or someone else—Booth, hopefully—than suffer through such a sentence.

While the old man’s star, such as it ever was, had first faded in the late eighties before pretty much winking out completely in the nineties (along with the majority of the B-movie production houses), the earlier films in particular continued to play on cable. To this day, on the highest movie channels, the ones that are all gore and tits and robots, a black-haired Booth can still be found battling evil with a plunger.

And now, the very same man—Satanologist, disgracer of Plato, annoying cloud, and his sole surviving parent—was accusing Sam’s script of the crime of portentousness.

“Let me put it this way,” said Booth. “I don’t find much in the way of generosity in the story. I’m worried that the irony is perhaps too thick.”

“Maybe I like my irony thick.” Sam went to the counter, poured himself coffee, and left it black. His father had awakened him from a dead sleep to offer his criticism and trailed him to the kitchen.

Sam sipped and burned his tongue. He spat coffee back in the cup. “Damn it.”

“Do you need an ice cube?” asked Booth immediately. He reached for the freezer door.

“No,” said Sam, annoyed at his father’s obsequiousness. “I just scalded my mouth a little. I’ll probably live.”

Booth dropped his hand and went on without another beat: “Irony is so easy, though, Samuel. It’s so simple to pull out the rug and make everything bleak and awful. Isn’t it more interesting to try and dig down into the hard dirt, and scrape out that precious nugget of possibility? Of redemption? Of humor? Of hope? Cynicism is the predictable route. Now: something hopeful! That would shock an audience, knock them back in their seats.” Booth was dressed in a gigantic pair of sky-blue pajamas. A big man in his youth, and an enormous man in these later years, he had the legs of a monument and the torso of a snowman. Sam was tall, but his father towered over him. “Certainly, there are many amusing moments, but it leaves an acutely bitter taste. You should at least give your characters a chance at happiness, don’t you think?”

Sam thought his father was completely wrong, about everything. He thought, “I don’t like you.” He thought, “It’s too early in the morning.”

A part of Sam wanted to yell, to just yell unintelligibly until his father shut up and went away. He had to concentrate hard on maintaining a tranquil front. With exaggerated care, he set his brimming coffee mug on the counter. “Hold on, Booth. Just—hold it.”

For as long as he could remember Booth had been “Booth.” He was aware that people found it off-putting that he called his father by his first name—that it came off as either severe or pissy or both, which, admittedly, it pretty much was—but to call him “Dad” would have felt like giving in.

Booth’s movies had nothing to do with reality. They had to do with killer rats and the car-wash Mafiosi and the outbreak of werewolf attacks in ancient Greece.

“You know—” Sam searched for a way to concisely summarize the man’s gall. To commit adultery was one thing. To break promises to your children was another. To do the things that Booth had done in movies—to rant and to brood and to stalk around like a tin-pot dictator on thousands of movie screens—was another. But to be guilty of all these trespasses, and then to carry yourself as though you were a serious person—The Most Serious Person—was something else altogether.

It wasn’t as though he had expected Booth to like the script, let alone understand it. Who We Are was about the hard reality of how quickly the days sped up, how suddenly you weren’t a kid any more. Booth’s movies had nothing to do with reality. They had to do with killer rats and the car-wash Mafiosi and the outbreak of werewolf attacks in ancient Greece. It annoyed Sam that he was annoyed by his father’s opinion, which was a meaningless opinion, and which he could have predicted.

There was so much he could have said, and wanted to say, and there was Booth, in his gigantic pajamas with that look of concern, as if he were not only entitled to offer his critique but actually cared. The words and the arguments became jammed up somewhere in Sam’s chest. “—Just—Who asked you, anyway? And why the hell are you going through my laptop bag?”

“I was going to write you a nice note and put it in there.” Booth raised an eyebrow at him. Errant gray hairs stuck out from the eyebrow like frayed wires. Several of the wires had dandruff.

“What was it going to say?” asked Sam immediately, eager to catch him.

“That I was proud of you! You’re a college man now.”

“Booth. Who looks in a bag to put in a note before they’ve even written the note?”

His father made an innocent face. “I needed paper to write my note.”

They stared at each other. The clifflike brow that hooded his father’s eyes gave him a haunted aspect. It also made him invincible in staring contests.

Sam broke away and snatched his coffee mug from the counter. A splash of hot liquid fell across his hand and fingers. He hated feeling like this, like he was a son and Booth was a father and they were arguing about whether curfew was eleven or twelve. It was embarrassing. “You know what? I want to go and drink my coffee now.”

“I am only being honest! You must admit that the whole story is heavy. There is, throughout, a sort of funereal drumbeat.”

“Okay, okay. What if, like, a gigantic hole opens up in the middle of the campus, and it swallows all the characters?” Sam asked. “Could there be some fun in that? And suppose if there were mimes, too, a visiting mime troupe, and we put them in the gigantic hole, and let them mime for their lives. How about that?”

“This poor young man who becomes a drug addict for instance, and then, abracadabra, turns into a little puddle of clothes. It is so harsh. And I do understand that college isn’t all fucking and giggles, but certainly it’s more fucking and giggles than you make it seem. And I also think that young people are more self-aware than you give them credit for being. In fact, most young people I know, especially the young females are—”

“—Do you listen to anything I say, Booth? Because I have this impression that, to you, my voice is on the same frequency as a dog whistle.”

“Samuel, I am not trying to offend you!” The exclamation was drafted in Booth’s Voice, the resonant, declamatory tone that he adopted to lend credence to things that were ridiculous, such as killer rats and the car-wash mafia and the werewolves of ancient Greece. “I am trying to help!”

His father blinked, very slowly, and in spite of all his experience, Sam found himself swayed to consider whether, this once, the man might mean what he was saying. He let the hot coffee drip over his hand and plink onto the floor. In the ceiling, the machine guts of the house ticked and hummed.

“Samuel.” Sam’s father cleared his throat, shook his head, and lifted the hem of his pajama shirt to absently swish a finger around in the gray-haired nest of his bellybutton. “I am your father and I only want the best for you”—Booth glanced down at the small meteor of hair and lint that he had mined from his navel, momentarily considered it, and then carefully placed the artifact aside on the kitchen counter—“and that means that, above all else, I must be honest.”

Honesty had hitherto, in the twenty-two years of their relationship thus far, not proved the slightest burden to Booth. He had taken every “chance at happiness” that he ever wanted—fucked anyone he wanted, said whatever he wanted, left whenever he wanted.

“Why can’t you even stand like a normal person?”

“What?” asked Booth, reading the look on his son’s face. “What is it?”

What was it? It was everything about him.

“That,” said Sam, and flung out a hand to indicate Booth’s gut.

“All right, all right, fine.” His father dropped his shirt and put up his palms. “All better?”

Sam finally took a gulp of his coffee. It tasted horrible. He drank some more. He breathed.

Booth waited in the pose of a man having his portrait painted, arms crossed, chin tipped slightly upward.

“Why can’t you even stand like a normal person?” Sam asked.

His father groaned. “Jesus Christ, Samuel. Have a heart. How do you want me to stand?”

“Okay,” Sam said. “I’ll grant you that it’s heavy. The story is heavy. So what?”

“So nothing!” Booth’s chuckle boomed around the kitchen. On film, he had utilized this same sonorous chuckle on many occasions, often when playing the role of an insane person. “It is a very grave work of art. There is nothing wrong with that.”

“Terrific. We agree. Thanks.” It was, finally, easier to submit. Sam thought about the drive to come, the privacy of his car, the security of his own apartment, his future, not having to see this man.

“You are perfectly welcome. But you see, this is a story about college students and you have endowed it with the gravity of the Manhattan Project. And that is what I mean when I say that it could be construed as a bit portentous.” Booth gave the counter a sharp knock for emphasis and beamed out the dormer above the sink, as if the stubbly, green yard was a country he had conquered. “Think about letting some light into the thing. You can do that, can’t you? Think about it.”

Sam nodded. He wasn’t changing a fucking thing.

“I should go,” Sam said. “It’s a long drive.”

“Good! That is all I wished to say. However it turns out, I am terribly proud of you.” Booth spread his arms wide. “You are, and always have been, and always will be, an incomparable delight to me, and—I am sure I don’t need to add—to your mother. She could not have loved you more. I could not love you more.”

Sam awkwardly patted his father’s arm and spun quickly to withdraw from hug range. “I really should go,” he said.

When it came to making the film, Sam began with two key advantages.

The first of these was that Who We Are could be made relatively cheaply. The script included no special effects, no costly Hollywood-style spectacles, no stunts, no explosions. Many other elements of a typical production were irrelevant: set design was unnecessary—the college was exactly what they needed it to be; the actors could provide their own wardrobes; and the conceit of the film was such that lighting continuity was not particularly important—all that mattered was that the “day” of the movie gradually fade into “night.”

Sam’s senior advisor had greased the wheels of the Russell College’s bureaucracy and arranged for twenty days of full access to the major locations in exchange for a relative pittance. On top of that, much of the necessary equipment was already available to borrow from the film department. To earn an independent study credit, a small group of juniors and seniors had eagerly signed on at no cost except board.

None of which was to say that the movie could be made for free.

Sam had determined to absolve himself in advance of any and all crimes, moral or otherwise, committed in the service of the film, from the first dollar raised to the locking of the final print.

The “relative pittance” that Russell required to allow them to tramp freely about the college grounds was enough to purchase a new car. Because the film department’s equipment had been manhandled by thousands of trust-fund fuckwits, there were still a number of pieces that he had to rent, including the camera and several lenses. The 16mm stock that Sam had decided to use was cheap by Hollywood standards, but not by any other standards. Developing fees, video transfer fees, and storage fees were significant and unavoidable. The cast and crew, meanwhile, did have to be fed, and though the summer rates for Russell’s dorm rooms were not exorbitant, the cost of a whole hall of them added up. Finally, if the film’s time conceit was to work, he was probably going to have to hire at least one true professional, a make-up artist who could effect the characters’ frequently shifting looks and hairstyles.

And those were just the things that he had to have. Should he strike a financing geyser, high atop Sam’s wish list was the rental of the carnival rides and attractions—Ferris wheel, tea cups, the duck-shooting galleries, etc.—that the college brought in every year for the actual May Festival. While he was prepared to make the film without them, their inclusion would add a degree of verisimilitude that couldn’t be otherwise created.

No matter how you cut it, rides or no rides, the movie needed at least thirty-five thousand dollars (and preferably three times that amount), every penny of which he needed to raise in less than a year.

Which led to the matter of his second great advantage: Sam had determined to absolve himself in advance of any and all crimes, moral or otherwise, committed in the service of the film, from the first dollar raised to the locking of the final print. Whatever bullying, manipulation, or duplicity was required, he was duty-bound and preforgiven to do what was best for Who We Are. When it was over he could strive to make whatever amends were possible.

“I don’t believe you,” Polly said. “You’re such a totally nice guy.” She was in Florida. Sam was on his couch in his apartment. It was October then, a couple of weeks after he’d seen Booth back home.

“Not about this. You only get one chance. It can’t suck.”

“Why not?”

This wasn’t to say she was beautiful—her tits were a little too big, her mouth was a little too big, and her bottom teeth were uneven. Rather, her allure came from her attitude, which was unapologetic, and her perspective, which yo-yoed between sunny and scandalized.

Since their breakup the previous spring the parameters of their relationship had grown murky. Through the end of the school year, they had continued to sleep together on occasion, and since Polly had returned home to live with her parents at their retirement community and take some time off before joining the workforce, they had been having semi-regular phone sex. Sam was careful not to probe too eagerly into the matter of whom besides her parents she had been spending time with, and he was deliberately vague about his own spare hours, not least because there was mortifyingly little to reveal. Since graduating and moving to the apartment, Sam hadn’t done much except work on the script and watch movies checked out from the library. He certainly hadn’t been getting laid.

Polly had the supple, amused voice of a sexy disc jockey, and Sam knew that, unlike a disc jockey, she was sexy in real life. This wasn’t to say she was beautiful—her tits were a little too big, her mouth was a little too big, and her bottom teeth were uneven. Rather, her allure came from her attitude, which was unapologetic, and her perspective, which yo-yoed between sunny and scandalized. Polly’s parents had been in their mid-forties when she was born, too old and tired to put up much of a fight, and their daughter was accustomed to getting her way. At Russell, she had studied to be a pre-school teacher. Sam thought she’d be a good one; Polly was smart, not afraid to be silly, but impossible to budge if she didn’t want to budge.

It was true that they had few shared enthusiasms. Polly was far more likely to want to curl up on the couch with a novel than go to a movie theater. Fat Russian novels were special favorites because, she said, the combination of sex, violence, and cold weather made her feel “safe and cozy, and so freaking lucky not to be a nineteenth-century Russian person.” Televised sports were another passion of hers that Sam couldn’t match. Pretty much anything besides golf and auto racing, she’d watch and sort of narrate what was happening, a habit that by all rights should have been tremendously annoying but which Sam found endearing. “Oh, look!” she’d exclaim after a football player scored a touchdown and all of his teammates piled on top of him. “They’re so happy!”

Sam sensed his hopes for phone sex were on the verge of slipping away.

Although Sam was fairly sure he didn’t love Polly, he liked her a lot—and couldn’t resist the way she wound him up.

“Why can’t it suck? Is this a trick question?” He could never be certain if Polly was being willfully obtuse in a flirtatious way, or just willfully obtuse.

“No,” she said. “I really want to know. And if you’re going to be crabby about it, maybe I ought to hang up right now.”

Sam sensed his hopes for phone sex were on the verge of slipping away. He dropped his feet off the couch and sat up. “It can’t suck because it can’t. Because I’m not making it to suck. Who goes into something that they really care about, and that’s really personal to them, and thinks, Oh, well, it’ll be okay if it sucks?”

“All I can say to that, my dear, is that you’ve clearly never been a woman.”

Sam was prudent enough to refuse the bait. Polly let him hang for ten or fifteen seconds. When she spoke again, he could hear her smile. “Of course you’re not making it to suck, but it’s not a matter of life or death. It’s a movie.”

Polly had never been able to comprehend what it was like to have Booth Dolan for a father. Just the opposite, in fact: after years of listening to Sam’s grievances, it was clear that she had come to regard his alienation from Booth as being pretty adorable. Sam didn’t suppose she’d ever understand—and perhaps this was part of the reason why, despite his attachment to Polly, that he couldn’t imagine them together in the long term—but since that morning and the talk with his father in the kitchen, he had brooded at length on his relationship with Booth. It now seemed to represent a final break.

One needed look no further than the old man’s quintessential role as the diabolical traveling salesman of cures and elixirs, New Roman Empire’s Dr. Archibald ‘Horsefeathers’ Law, to understand that a movie wasn’t a matter of life and death. It was life and death.

In 1969 Sam’s father had produced, directed, written, and starred in New Roman Empire, a no-budget horror movie about hippie teenagers brainwashed by a cornpone Pied Piper. It was a naked allegory wherein Booth’s character, Dr. Archibald ‘Horsefeathers’ Law, appeared as the wicked hand of Nixonian politics, sending dazed hippies to their deaths á la Vietnam. It had been a modest success on the drive-in circuit and to this day maintained a cachet, primarily among B-movie superdorks. (It was telling, Sam felt, that along with their enthusiasm for Booth, this breed of cinephile could be relied upon to have an encyclopedic knowledge of Ed Wood, women-in-prison films, and all the monsters that had fought Godzilla.)

Perhaps he had been a different person before New Roman Empire, but ever since—as long as Sam had known him—Booth had played the role of the magnificent bullshitter ceaselessly. Two busted marriages, two children he saw infrequently, and he talked and he talked without ever saying anything.

Early on in the film, Dr. Law—Horsefeathers—holds forth before a crowd of skeptical hippies. He is a grinning fat man in a checkered suit and a bowler hat.

“I am not a miracle worker!” Horsefeathers cries, removing his hat with flourish, letting it tumble end-over-end along his arm. The charlatan casts around, fixing the eyes of each person in turn. In the background, an off-kilter caper begins, plucked on warbling strings. “I am a physician specializing in the deeper body. There is no magic about this. My medicine is, quite simply, a scientific treatment for the soul!”

Perhaps he had been a different person before New Roman Empire, but ever since—as long as Sam had known him—Booth had played the role of the magnificent bullshitter ceaselessly. Two busted marriages, two children he saw infrequently, and he talked and he talked without ever saying anything.

It didn’t matter, as Sam’s best friend, Wesley Latsch, pointed out, that everyone’s father had cheated on everyone’s mother, and that everyone’s father was mortifying and insufficient in a thousand ways. “You take your old man far too personally,” Wesley said, and Wesley was right. Sam’s resentment was achingly common.

But it just didn’t matter: because Booth was Booth, and Booth was his father.

Who We Are was only a small independent movie. It might never find distribution, might never make it beyond a few minor Midwestern film festivals. But it was important to Sam. It was his statement, his vision, his movie. It wasn’t just supposed to be a couple of hours of escape, of people running around and splatting each other in the face with pies. To him, it was serious. Who We Are was about the costs of growing up—and the costs of not growing up. And that was heavy stuff, and Sam made no apology, not to Booth, not to anyone. Maybe it wasn’t fun, and maybe it wasn’t entertainment, but he was going to show them something real.

“I mean, it’s not even a big movie. It’s not like one of these ones with elephants and submarines and everything in it,” Polly went on. “You’re acting like it’s the biggest thing.”

“What movie has elephants and submarines?”

“Don’t be a snot. You know what I mean. Like Stars Wars.”

Sam decided he’d better throw the track switch before Polly started to prod him about his childhood, or his fears, or some other libido-extinguishing subject.

“Look, Polly, to me, it is pretty much the biggest thing ever. To me it’s a lot of money and a hell of lot of work, and I’ve put a lot of thought into it. And all I’m saying is that if I have to kick some ass to make it what I need it to be, then I’m prepared to do that. I’ve never cared about anything so much, ever.”

“Well, well, well. That’s quite a statement, young man. Ever?”

“Ever.” Sam decided he’d better throw the track switch before Polly started to prod him about his childhood, or his fears, or some other libido-extinguishing subject. “Let me give you an example: if to get this film made requires me to debase myself over the phone, follow the whims of some depraved sex maniac in Florida, I’m prepared to do that.”

“No!” Polly cried. “Absolutely not! I just want to have a nice conversation for once. Besides, you just told me how you were going to squash all us little people to make your opus. I no longer trust your motives.”

“I didn’t say that. I’ve never said the word ‘opus’ in my life.” Frustrated, Sam rose from the couch, and began to pace across the twenty or so feet of his apartment’s living space. It had come pre-furnished with a desk, a single bed, a strip of maroon carpet remnant, a dusty plant, and a kitchenette, the cabinets of which so far contained only one plastic plate and a mostly empty spray bottle of Febreze, both left by the previous resident. The window by the desk offered a view of the parking lot and the identical, neighboring sections of the gray-walled, grayer-roofed development. Sam looked out the window and saw a couple of boys were spitting into the medicine ball-sized pothole in the parking lot. The huge pothole was the landmark he used to find which part of the development he lived in.

“Let’s just talk about something else. What else is happening?”

Sam asked her if he had mentioned the odd, heady smell of the hallways in the complex, like a drugstore, like Silly Putty, that medicinal-industrial odor. Polly said yes, he’d mentioned it. Had she told him about the dear biddy who lived in the neighboring bungalow and knocked on the door at four in the morning to bring them a fresh-picked gourd? He said she had. They were both so careful to stay clear of each other’s social lives, there wasn’t much left over.

“I was afraid that we’d become old and uninteresting,” Polly said. “I just didn’t expect it to happen so soon. What happened to the fascinating boy that I went to college with, Sammy?”

“Well, shit, Polly. I don’t know. Hey, are you going to invest in my movie, or what?”

“See, polite is sexy,” she said, and smacked her lips. “Okay, bitch! Take off your pants, go to the refrigerator, and get out the butter.”

Polly shrieked. “Now I feel really soiled! First you want me to help you masturbate, then you turn dull, and then you ask me for money. What’s next?”

“You give me money?”

“What’s the magic word?”

“Please?”

“More.”

“Pretty please? Pretty, pretty please?”

“See, polite is sexy,” she said, and smacked her lips. “Okay, bitch! Take off your pants, go to the refrigerator, and get out the butter.”

Sam didn’t have any butter—or margarine—but along with the plate and the mostly empty sprayer of Febreze, his predecessor had also bequeathed him a huge jug of electric-blue liquid soap called “The Blue,” whose label bore a cartoon of an impressively coiffed shark. Once he had retrieved the jug from the bathroom, he yanked down the window shade, and jumped on to the bed. Sam wriggled out of his pants and boxers, squirted out a big handful of blue soap. “Got it. Now what?”

Polly directed him to rub up his stuff real good. “But don’t you dare ejaculate before I tell you! Not so much as a dribble!” Sam was close after four or five hard strokes, so he slowed down, limiting himself to the occasional paddle.

For the first time, Polly mentioned that she was alone in her house. Mr. and Mrs. Dressler had gone to the local clamshack for the early-bird special, and here she was in her panties, and now here she wasn’t in her panties. “Oh, look,” she said, “the dining room table…” There was a creaking sound as she climbed on top of it—or somehow, like a Foley artist, concocted a noise that perfectly replicated the sound of a one-hundred-and-ten pound woman climbing onto a Shaker-style dining room table, which struck Sam as fairly unlikely. Polly informed him that she was pulling up her skirt, lying on her back. The wood was nice and cool against her ass, and across from the table, on the wall behind her daddy’s chair, there was a mirror. “And I can see all the way into myself, Sammy.”

“The Blue” was lathering around his penis and dripping bubbles into his pubic hair, spilling onto the sheets of his bed, making a mess. At the same time, he was trying to keep the soap away from the tip of his penis, because who knew what the hell was in “The Blue.”

“Jesus,” Sam said. He had started to speed up again and now had to squeeze himself to hold off.

“Sammy.” In a whisper now Polly described how she was fingering herself, sliding her finger up and down, separating the hot, slick folds. He better be buttering himself; she was so incredibly tight, they were going to need all the help they could get. “Sammy, Sammy, Sammy…”

“The Blue” was lathering around his penis and dripping bubbles into his pubic hair, spilling onto the sheets of his bed, making a mess. At the same time, he was trying to keep the soap away from the tip of his penis, because who knew what the hell was in “The Blue.” There was a dangerous tingle along his shaft, which might have been his imagination. But he was huge, digging his heels into the mattress, shaking all over; Sam could see clearly enough that what was exciting was that Polly was telling him what to do, that it was unlike every other aspect of his existence, wherein he struggled to contain and order. He had a suspicion that he was not the only director who, when it came to sex, liked to switch roles.

“Are you filming me? I want you to film this. This is my movie. My movie.”

“Okay.”

“Whose movie is it?”

“Yours, Polly.”

“Good. Are you ready? Are you on your mark?”

“Uh-huh,” Sam managed to say, and when Polly said, “Go!” he was gone.

He asked Polly if she came, too. “Eh,” she said.

“Do you want to keep going?” Sam sort of hoped she didn’t. He wanted to clean up before anything dried. Gobbets of blue soap, bubbles, and semen were mixed and spattered on his genitals, thighs, left hand, and the sheets between his legs. It looked like a member of the Blue Man Group had been shanked to death.

Holding a mingled puddle of soap and genetic material in his cupped hand, he maneuvered himself off the bed and around the kitchen bar to the sink. Sam tucked the phone between his ear and shoulder, turned on the faucet with his clean hand, and stuck his semen-and-soap hand under the water.

“Well…” she said.

“What?”

“Would you mind asking me again? For money?”

Now it was Sam’s turn to feel soiled, but he had made a promise to himself—he would do what he had to. At least Polly was a friend. So he asked her again, and again, and again, please, pretty please, please with sprinkles.

Three days later he received his reward in the mail: the first investment in the film, a two-hundred-and-fifty-dollar check from Ms. Polly Dressler. The subject line read, “for the BIGGEST thing ever!!!”

Owen King is a graduate of Vassar College and the MFA program at the Columbia University School of the Arts. He is the author of We’re All in This Together: A Novella and Stories, as well as the co-editor of Who Can Save Us Now? Brand-New Superheroes and Their Amazing (Short) Stories. His writing has appeared in One Story, Paste Magazine, Prairie Schooner, and Subtropics, among other publications. Owen has also taught creative writing at Columbia University and Fordham University, and is a working screenwriter with a script in development at Anonymous Content by the producer of Winter’s Bone. He is married to the novelist Kelly Braffet.

Copyright © 2013 by Owen King. From the forthcoming book DOUBLE FEATURE by Owen King to be published by Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Printed by permission.