Many stories are told about the T’ang dynasty artist Wu Daozi, sometimes named as one of the three great sages of China: that he ignored color and only painted in black ink, that he transgressively painted his own face on an image of the Buddha, that he painted a perfect halo in a single stroke without the aid of compasses, that he painted pictures of the dragons who cause rain so well that the paintings themselves exuded water, that the Emperor sent him to sketch a beautiful region and reprimanded him for coming back emptyhanded, after which he painted a 100-foot scroll that replicated all his travels in one continuous flow, that he made all his paintings boldly and without hesitation, painting like a whirlwind, so that people loved to watch the world emerge from under his brush.

One story about him I read long ago I always remembered. While he was showing the Emperor the landscape he had painted on a wall of the Imperial Palace, he pointed out a grotto or cave, stepped into it, and vanished. Some say that the painting disappeared too. In the account I thought I remembered, he was a prisoner of the Emperor who escaped through his painting. When I was much younger I saw another version of this feat that impressed me equally.

In an episode of the Sunday morning cartoon Roadrunner and Coyote, the eternally hopeful predator makes a trap for the bird. At the point where a road ends in a precipice, he places a canvas on which he paints an extension of the road, complete with the red cliff on one side and the guard rail on the other. The roadrunner neither smashed into the painting nor fell through it, but ran into it and vanished around the painted bend. When the coyote attempted to follow him, he broke through the painting, plummeted, was smashed up, and then, yet again, as always, he was resurrected. Your door is my wall; your wall is my door.

The one creature embodied grace, the other foolish desire, as though they were two elemental principles that could never mingle, in body or spirit. Chuck Jones’s Wile E. Coyote is a version of the great creator deity of the North American continent, Coyote. This is the god whose eyes and cock sometimes detach to seek their own satisfactions, who is often broken, occasionally killed, always resurrected, and never annihilated, who represents the comic principle of survival. But only as I write do I also notice the bird is a Taoist master, like the calm masters nothing could touch in the stories of old China. They walked through fire, through rock, and on air with aplomb.

These feats of the bird and the painter are paradoxical and impossible, but only literally, or only in some media. People disappear into their stories all the time. We live in stories and images, as immersed in them as though they were Wu Daozi’s inkpots; we breathe in presuppositions and exhale further stories. We in the west have been muddled by Plato’s assertion that art is imitation and illusion; we believe that it is a realm apart, one whose impact on our world is limited, one in which we do not live.

Writers are solitaries by vocation and necessity. I sometimes think the test is not so much talent, which is not as rare as people think, but purpose or vocation, which manifests in part as the ability to endure a lot of solitude and keep working.

Sticks and stones may break my bones but words will never hurt me, my mother liked to recite, though words hurt her all the time, and behind the words the stories about how things should be and where she fell short, told by my father, by society, by the church, by the happy flawless women of advertisements. We all live in that world of images and stories, and most of us are damaged by some version of it, and if we’re lucky find others or make better ones that embrace and bless us.

As I wrote this, my friend Annie sent me a note from Easter Island, where she was working on a radio story. She wrote me of “sweeping grasslands, dormant volcanoes, sheer black volcanic cliffs dropping into the sea and those magnificent, stern moai”—the great stone heads—“scattered all over the island. I can’t stop wondering what possessed the Rapa nui to build them and then after that was over to conceive of the birdman cult.” Hundreds of years after the cultural near-extinction of their makers, the heads were still provoking thought; they were still in our heads; Annie wrote to me and put the birdman cult in mine.

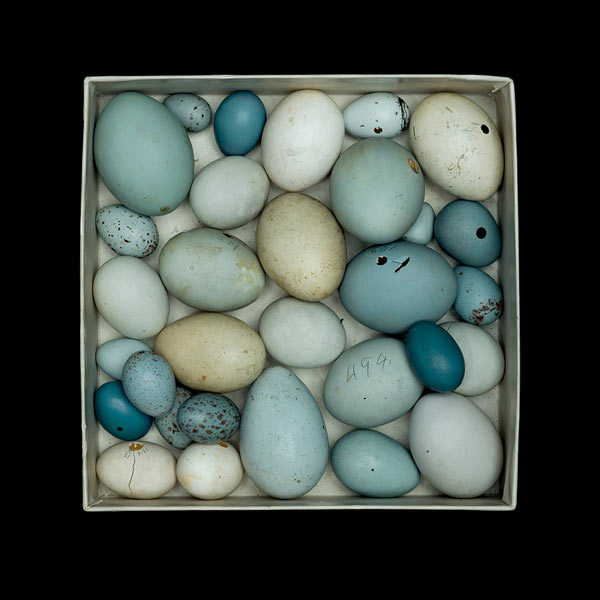

After their devastating contact with the European world, beginning on Easter of 1722, the Rapunui, the Easter Island people, made the cult with its dangers and arbitrarinesses more central to their lives. Those who had the gift of prophesy would choose the contestants in their dreams. To be dreamed of was a dangerous thing. The contestants would swim to an islet off the coast, attempt to collect the first sooty tern egg of the season, swim back, then scale a cliff without breaking the egg. The losers sometimes drowned, or were devoured by sharks, or fell from the cliff. The winner was given a new name and isolated but splendid status for the year, and his clan won the exclusive rights to the season’s egg-gathering from the small island where the tern’s egg had been seized.

The birdman cult might be just an extreme case of the stories we weave all the time that make a small item a trophy, a sign of spiritual or social status, a token that changes your life. Only the unfamiliarity of the birdman cult makes us remark on its arbitrariness, since in our own world people die in the attempt to climb mountains for no practical reason, kill because of words that insult them or their gods, and revere those who have won a prize handed over by a whimsical jury or because a combination of factors sent a ball into or over a net.

We live in dreams; we go into the shark-filled sea to carry them out; they make one egg of the sooty tern, also known as the wideawake, into something you can organize a whole society around. The tern’s egg is small, speckled, and nondescript. The god who presided over all this was named MakeMake. “The things we dream up…” wrote Annie. To become a maker is to make the world for others, not only the material world but the world of ideas that rules over the material world, the dreams we dream and inhabit together.

Libraries are sanctuaries from the world and command centers onto it: here in quiet rooms are the lives of Crazy Horse and Aung San Suu Kyi, the Hundred Years War and the Opium Wars and the Dirty War, the ideas of Simone Weil and Lao Tsu, information on building your sailboat or dissolving your marriage…

Like many others who turned into writers, I disappeared into books when I was very young, disappeared into them like someone running into the woods. What surprised and still surprises me is that there was another side to the forest of stories and the solitude, that I came out that other side and met people there. Writers are solitaries by vocation and necessity. I sometimes think the test is not so much talent, which is not as rare as people think, but purpose or vocation, which manifests in part as the ability to endure a lot of solitude and keep working. Before writers are writers they are readers, living in books, through books, in the lives of others that are also the heads of others, in that act that is so intimate and yet so alone.

These vanishing acts are a staple of children’s books, which often tell of adventures that are magical because they travel between levels and kinds of reality, and the crossing over is often an initiation into power and into responsibility. They are in a sense allegories first for the act of reading, of entering an imaginary world, and then of the way that the world we actually inhabit is made up of stories, images, collective beliefs, all the immaterial appurtenances we call ideology and culture, the pictures we wander in and out of all the time. In the children’s books there are inanimate objects that come to life, speaking statues, rings and words of power, talismans and amulets, but most of all there are doors, particularly in the series that I, like so many children, took up imaginative residence in for some years, The Chronicles of Narnia.

I read one in fourth grade after a teacher who barely knew me handed it to me in the school library; I can still picture his mustache and the wall of books. I read it and read it again and then began to save up to buy the seven books, one at a time. The paperbacks came from the enchanted bookstore in the middle of town, whose kind proprietor rewarded me with the case in which the seven books fit when I had paid for the last one. I still have the boxed set, a little tattered though I think no one has ever read them other than me. When I took one out recently, I noticed how dirty the white back of the book was from my small filthy fingers then.

Much has been written about the Christian themes, British boarding school mores, and other contentious aspects of the series, but little has been said about its doors. There is of course the wardrobe in the first book C. S. Lewis wrote, the wardrobe made of wood cut from an apple tree grown from seeds from another world that, when the four children walk into it, opens onto that world. Two of the other books feature a doorway that stands alone so that when you walk around it it’s just a frame, three pieces of wood in a landscape, but when you step through it leads to another world. There’s a painting of a boat that comes to life as the children tumble over the picture frame into the sea and another world. There are books and maps that come to life as you look at them.

And there is the “Wood Between the Worlds” in the book The Magician’s Nephew, which tells the creation story for Narnia, a wood described so enchantingly I sometimes think of it as a vision of peace still. It’s more serene and more strange than the busy symbolism in the rest of the books, with their talking beasts, dwarves, witches, battles, enchantments, castles, and more. The young hero puts on a ring and finds himself coming up through a pool to the forest.

“It was the quietest wood you could possibly imagine. There were no birds, no insects, no animals, and no wind. You could almost feel the trees growing. The pool he had just got out of was not the only pool. There were dozens of others—a pool every few yards as far as his eyes could reach. You could almost feel the trees drinking the water up with their roots. This wood was very much alive.” It is the place where nothing happens, the place of perfect peace; it is itself not another world but an unending expanse of trees and small ponds, each pond like a looking glass you can go through to another world. It is a portrait of a library, just as all the magic portals are allegories for works of art, across whose threshhold we all step into other worlds.

Writing is speaking to no one, and even when you’re reading to a crowd, you’re still in that conversation with the absent, the faraway, the not-yet-born, the unknown and the long-gone for whom writers write, the crowd of the absent who hover all around the desk.

Libraries are sanctuaries from the world and command centers onto it: here in quiet rooms are the lives of Crazy Horse and Aung San Suu Kyi, the Hundred Years War and the Opium Wars and the Dirty War, the ideas of Simone Weil and Lao Tsu, information on building your sailboat or dissolving your marriage, fictional worlds and books to equip the reader to reenter the real world. They are, ideally, places where nothing happens and where everything that has happened is stored up to be remembered and relived, the place where the world is folded up into boxes of paper. Every book is a door that opens into another world, which might be the magic that all those children’s books were alluding to, and a library is a Milky Way of worlds. All readers are Wu Daozi; all imaginative, engrossing books are landscapes into which readers vanish.

The object we call a book is not the real book, but its seed or potential, like a music score. It exists fully only in the act of being read; and its real home is inside the head of the reader, where the seed germinates and the symphony resounds. A book is a heart that only beats in the chest of another. The child I once was read constantly and hardly spoke, because she was ambivalent about the merits of communication, about the risks of being mocked or punished or exposed. The idea of being understood and encouraged, of recognizing herself in another, of affirmation, had hardly occurred to her and neither had the idea that she had something to give others. So she read, taking in words in huge quantities, a children’s and then an adult’s novel a day for many years, seven books a week or so, gorging on books, fasting on speech, carrying piles of books home from the library.

Writing is saying to no one and to everyone the things it is not possible to say to someone. Or rather writing is saying to the no one who may eventually be the reader those things one has no someone to whom to say them. Matters that are so subtle, so personal, so obscure that I ordinarily can’t imagine saying them to the people to whom I’m closest. Every once in a while I try to say them aloud and find that what turns to mush in my mouth or falls short of their ears can be written down for total strangers. Said to total strangers in the silence of writing that is recuperated and heard in the solitude of reading. Is it the shared solitude of writing, is it that separately we all reside in a place deeper than society, even the society of two? Is it that the tongue fails where the fingers succeed, in telling truths so lengthy and nuanced that they are almost impossible aloud?

I had started out in silence, written as quietly as I had read, and then eventually people read some of what I had written, and some of the readers entered my world or drew me into theirs. I started out in silence and traveled until I arrived at a voice that was heard far away—first the silent voice that can only be read, and then I was asked to speak aloud and to read aloud. When I began to read aloud another voice, one I hardly recognized, emerged from my mouth. Maybe it was more relaxed, because writing is speaking to no one, and even when you’re reading to a crowd, you’re still in that conversation with the absent, the faraway, the not-yet-born, the unknown and the long-gone for whom writers write, the crowd of the absent who hover all around the desk.

Sometime in the late nineteenth century, a poor rural English girl who would grow up to become a writer was told by a gypsy: “You will be loved by people you’ve never met.” This is the odd compact with strangers who will lose themselves in your words and the partial recompense for the solitude that makes writers and writing. You have an intimacy with the faraway and distance from the near at hand. Like digging a hole to China and actually coming out the other side, the depth of that solitude of reading and then writing took me all the way through to connect with people again in an unexpected way. It was astonishing wealth for one who had once been so poor.

Reprinted by arrangement with Viking, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. from THE FARAWAY NEARBY by Rebecca Solnit. Copyright © Rebecca Solnit, 2013.