I was thirteen when Kurt Cobain died, and entirely more interested in the Jurassic Park soundtrack than Nirvana. I watched the MTV coverage of his death with my mother, who sat in a recliner ignoring a novel in her lap and saying over and over that it was so sad, that it was just like Jimi Hendrix. “You’re gonna remember this,” she warned, knowing I was still too young. She grew up in the sixties, an era whose narrative lingered like the sounds of a carnival after you’ve left. Catastrophic deaths had mile-marked her youth: JFK, MLK, Marilyn, Janis, Jimi. She paired each tragedy with a coordinate in space-time where/when she had received the news, and the result was an archive of snow-globe moments, each paused in the ether of their impending resonance.

Kurt was my first such tragedy and there I was on my living room floor, sitting on my feet, my hand deep in a can of Pringles. I was supposed to remember that forever.

A predictable group of kids seemed affected by Cobain’s suicide—mostly the ones who listened to their Walkmans in the hallway between classes. They claimed it was unfair, that he was too good for the world, and spent study hall carving Nirvana lyrics in blue ink into their paper-bag book covers. Somebody’s cousin swallowed a bottle of Tylenol and had to spend the night in the ER. This seemed overly dramatic, even to my thirteen-year-old brain, hard-wired for extreme emotion and catastrophe. I didn’t understand what they believed they had lost.

A week later a boy who played trumpet in the school band, and with whom I had been infatuated all year, stepped out onto his back porch, thoughtfully armed with some Kurt Cobain paraphernalia, and shot and killed himself. He was fourteen.

People like to ask if I saw it coming but nobody really sees it coming, even if it is laid out for you like the Fibonacci sequence. What they’re really asking is: Could you have stopped it? The answer will always be maybe, but Brett exhibited no more suicide warning signs than any teenager traversing pimply, fumbling, lopsided adolescence. It could have been anyone. And in a way, it had to be someone, the same way we expect an aftershock to follow an earthquake. Brett’s death made sense in a morbidly sequential manner: hero falls, admirers follow with the force of unused napkins sucked out the window of a moving car. Physicists call this kinetic energy. Sociologists call it copycat suicide. Our parents called it a tragedy and we called it fucked up or obvious or unbelievable, even when calling it anything seemed pointless, like waking from a lucid dream and trying to capture its vividness in a diary.

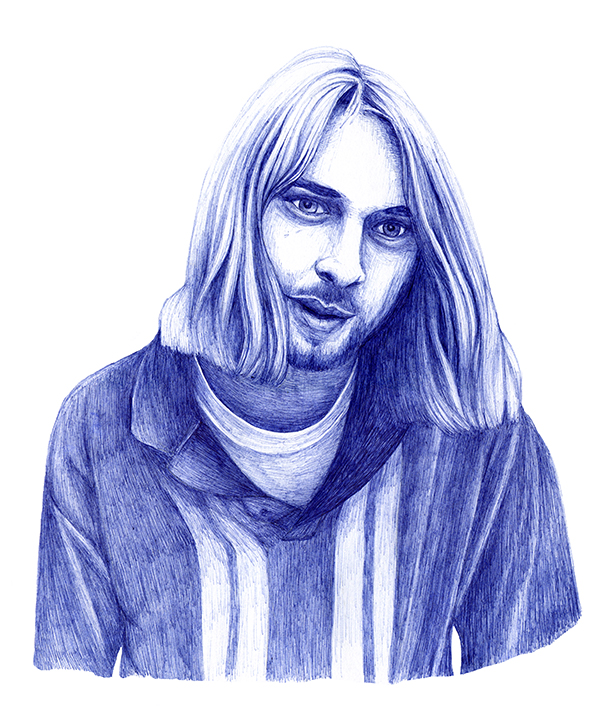

In celebration of the twentieth anniversary of Nirvana’s Nevermind, Seattle’s Experience Music Project Museum features an exhibit called Nirvana: Taking Punk to the Masses. Visitors are greeted with a massive wall-mounted photo of Kurt Cobain mid-jump, guitar in hands, blond hair paused on its way up or down. The reproduction of his Converse sneaker is the size of a newborn baby and I photograph it. A wall label tells me fans have interpreted this image as Cobain ascending heavenward and I think about the ways in which certain deaths swell ordinary moments into forewarnings. This is especially true for those who are perceived to have died tragically before their time—the Ritchie Valenses and the Jean Harlows and all the members of the 27 Club. Cause of death: a world that could not handle their potential.

It is July and the place swarms with guided tours and retired couples checking Seattle off bucket lists. A school of six-year-olds dressed in tie-dyed t-shirts flocks to interactive kiosks that map out the grunge music scene. The kids slip on oversized headphones and press any button their fingertips can reach. I suspect they will understand Nirvana with the distant appreciation I reserve for Hendrix, a near history whose consequences I can trace but whose true significance I can only partially understand.

Caged and catalogued, it is hard to believe Kurt Cobain’s influence was once considered a threat to my impressionable generation.

The exhibition’s nucleus is a reliquary filled with remains from Nirvana’s short life. The bodies of Cobain’s shattered guitars posed behind glass like butterflies. A familiar beige cardigan draped over a plastic torso, thumbholes torn in the wrist cuffs. I am drawn to waist-high Plexiglas display cases that contain the more intimate pieces: handwritten notes, creased set lists, three-by-five Kodaks once passed from hand to hand in the living rooms of strangers. I feel close to Kurt in the way that wearing antique jewelry makes you feel close to its previous owner. Caged and catalogued, it is hard to believe his influence was once considered a threat to my impressionable generation. Two decades later, children are free to peruse his dulled belongings. How much time must pass for idolization to stop being dangerous?

We remember Kurt Cobain as a multitude of men: a rock star, a heroin addict, a father, a punk hero, a spokesperson for our generation, a man who ended himself because he was not emotionally equipped for the breed of fame and attention we bestowed upon him. His death only slightly altered our perception, adding martyr to that already sizable list. He never quite receded from the spotlight, and although his musical influence is often compared to John Lennon’s, his legacy is closer to someone like Elvis’s—the legacy of someone whose death we don’t really want to acknowledge, whose impact resonates.

We do not often remember the immediate aftermath of Cobain’s suicide, a short time during which a palpable sense of grief spread among fans who saw in him not a leader but a reflection of themselves. To lose him was to lose faith that ordinary people could be extraordinary. “It’s hard to be a young person nowadays,” a college student told the New York Times on the day the news hit. They found her mourning Cobain’s death outside his Seattle home in the rain. “He helped open people’s eyes to our struggles.”

The media made much of the threat of copycat suicide, instilling fear in concerned parents and inspiring guidance counselors to hand out dusty xeroxed pamphlets listing suicide’s warning signs. Cobain’s was arguably the first major celebrity suicide since Marilyn Monroe’s death in 1962, and his influence was arguably more infectious. The adults expected suicide to spread like a fatal strand of mononucleosis, picking off the alienated and the vulnerable. Cobain copycats became a suburban legend, one that we knew held some truth; if the contagion found its way to our nowhere Connecticut town, that must have meant it was real, that we were part of some bigger phenomenon.

Collecting data about copycat suicide is like trying to calculate the number of weddings called off due to cold feet; you can track a general change in statistics, but you cannot determine whether one suicide directly inspired another unless the motivating factor is somehow made explicit. Even then, researchers don’t typically have access to that evidence—suicide notes, clues left at the scene, bystanders who might sift their memories for bits of fading conversations. They base their findings on mortality statistics, numbers that put all deaths into one of four categories: natural, accidental, homicide, suicide. From there, the best they can do is search for patterns and clusters, look at timing. Reason will always be absent.

In 1996, a group of experts teamed up to dissect the ripple effects of Cobain’s death in a paper called “The Kurt Cobain Suicide Crisis.” They intended to investigate widely held rumors that his suicide had led to a series of copycats. “Cobain’s death had all the potential ingredients to stimulate vulnerable youth to imitate and follow,” they wrote. “He was a cultural icon, a hero to a legion of identification-hungry youth.”

The numbers never materialized. After isolating statistics from the seven-week period following Cobain’s death, the researchers discovered twenty-four documented suicides in the Seattle area, a fairly average count relative to surrounding years. The number had actually decreased from thirty-one the previous year.

This is attributed in part to the media. Cobain’s death overtook the press, but the people reporting were generally not the same people who were mourning; they were the adults, a generation removed from the chaos. Cobain’s death made the cover of Rolling Stone but also the covers of Newsweek, People, Entertainment Weekly—magazines our parents got, magazines you’d find dog-eared on a chair in a dentist’s office. Most reporters treated the situation with curiosity and delicacy—perhaps anticipating the potential repercussions—careful to clearly distinguish Cobain’s life and music from the depression and drug abuse that led to his demise. “The shock and sadness felt by Cobain’s fans were not likely to lead to much imitation,” Newsweek reported, nine days after his body was found. “As The Who said long ago, the kids are all right; it’s one thing to walk around in torn jeans like a rock star, and another to put a bullet in your brain.” Fans were acknowledged and pointed in the direction of suicide hotlines.

On the far end of the generational divide was Andy Rooney, bitter and scowling. “What would all these young people be doing if they had real problems like a Depression, World War II, or Vietnam?” he said on 60 Minutes, shortly after Cobain’s death. “No one’s art is better than the person who creates it. If Kurt Cobain applied the same brain to his music that he applied to his drug-infested life, it’s reasonable to think that his music may not have made much sense either.”

Rooney faced backlash for his crass commentary both on Cobain and on suicide and despair. “Speaking of Mr. Cobain’s suicide at the age of 27, Mr. Rooney brought to the issue of youthful despair a mixture of sarcasm and contempt,” wrote New York Times columnist Anna Quindlen. “Not surprising, but worth noting because in 1994 that sort of attitude is as dated and foolish as believing that cancer is contagious.”

But Andy Rooney was not speaking to the youth; he was speaking to his peers, equally curmudgeoned and unable to identify with Cobain. The most resonant message may have come from Kurt Loder, then an MTV News journalist reporting on Cobain’s death from the proverbial front lines. In the absence of the Internet, MTV was where most fans would have gleaned the first details. At the end of his special report on The Week In Rock, the notoriously stone-faced Loder left viewers with a piece of advice: “Young people have been calling into radio stations all across the country, expressing the thought that they are feeling very depressed themselves and feeling sort of suicidal—don’t do it. Kurt Cobain’s tragic death wasn’t celebrated in this show. His music and his life were celebrated, but not his tragic death.”

In a brief pause, he almost hints at emotion. Like Walter Cronkite removing his thick-rimmed glasses for JFK.

“If you’re feeling upset or depressed by this news, please call your local suicide hotline, or if it’s an emergency, dial 911.”

“In short: don’t do it.”

Researchers link a single Seattle suicide to Cobain’s: 28-year-old Daniel Kaspar, the lone imitator, whom the “Cobain Suicide Crisis” study calls a “virtual prototype copycat.” The conditions of his death mirrored Cobain’s, as did those foreshadowing it: depression, substance abuse, thoughts of suicide. That résumé alone makes Kaspar a textbook case, someone for whom Cobain was only a catalyst.

Along with seven thousand other Nirvana fans, Kaspar attended Cobain’s candlelight vigil at Seattle Center’s Flag Pavilion Plaza, two days after Cobain’s body was found. After the crowd dispersed, he and his friends had some beers in Seattle before heading back south toward the suburbs where they lived. It was Sunday. Kaspar worked in a chemical plant in Tacoma and probably wanted to end the weekend at a reasonable hour. He was home by 11 and dead by 6 a.m., a gunshot wound to the head.

Kaspar’s friends were shocked. “Two weekends ago, we were all sitting out on our front porch talking about when the pool would open,” his apartment manager told the Seattle Times. Another friend said that Kaspar was a fan, but not a worshiper. That he talked about Cobain’s death, but didn’t seem particularly upset. “We were in an excellent mood,” the friend recalled after the vigil. “We had a good time.”

He and Kaspar had parted ways at about 10:30 p.m. “He said, ‘I’ll see you in the morning.’”

Unlike John Lennon’s Central Park vigil in 1980, Cobain’s was a highly organized affair with an agenda and a median age of seventeen. The plan was to acknowledge that Nirvana fans had experienced a huge loss, but also to shape that loss, to educate vulnerable kids that suicide is not the answer.

The audience believed they were there to mourn a fallen hero, but they were simultaneously receiving the most public and potent dose of suicide prevention the media had ever been able to administer.

The concept of the vigil was pioneer and risky, but also brilliant. There would be no other opportunity to gather thousands of grieving fans en masse for what was essentially a huge, internationally televised support group meeting. The audience believed they were there to mourn a fallen hero, but they were simultaneously receiving the most public and potent dose of suicide prevention the media had ever been able to administer. The Seattle Crisis Clinic even made an appearance, taking the stage to provide a clinical perspective on Cobain’s death. “Kurt Cobain has killed himself and we are left as survivors to make sense of this death,” representative Sue Eastgard said to the crowd. Her plainness stood out against the conflux of oversized t-shirts and shaggy, unwashed hair. She looked like somebody’s mom. “There is anger. There are feelings of sadness. We don’t understand why. And the difficult part about suicide is that the answers are taken away with Kurt. He knew the whys.”

“There is life after this death,” Eastgard later told a CNN reporter. “There is a need to pick up the pieces, to feel the sadness, certainly to feel angry and to feel betrayed by this man. But this is not cause for more suicides.”

Sue Eastgard has worked in suicide prevention most of her life. After directing the Seattle Crisis Clinic, she moved on to lead the Seattle Youth Suicide Prevention Program—a Washington-based nonprofit that sets the bar for national youth suicide prevention and education efforts. Since retiring, she has helped establish an organization called Forefront, the new state-funded hub of innovative suicide prevention strategies for professionals and educators across Washington State. She has spent most of her life as a clinician, which makes her more personable than many of the psychologists and sociologists I’ve met who care from a safer distance, interpreting suicide as a series of rising and falling statistics.

Sue gets people, which is probably why she is so good at what she does. She’s not afraid to curse and raise her voice and I feel instantly comfortable in her presence when we meet at a Peet’s Coffee outside Seattle’s Green Lake Park.

Like most experts in her field, Sue was at the American Association of Suicidology’s annual conference in New York when the news about Cobain hit the airwaves. Her son, fifteen at the time, had tagged along on the East Coast trip. After a Friday afternoon session, she returned to their hotel room to find him mesmerized by the television, aghast at the news about some unfamiliar rock star’s suicide.

“I didn’t even know who Kurt Cobain was,” Sue tells me, laughing at her own naïveté. “Then the clinic starts calling my hotel, telling me they’re inundated with calls from the Seattle media looking for guidance on how to report his death.”

She cut her New York trip short and returned to Seattle to help the clinic deal with the chaos. On Saturday she received a call from one of the radio stations organizing the vigil. They asked if she would make an appearance to represent the clinic.

“I told them I’m not coming to mourn,” she says. “I’m coming with a message of hope, with a place to call.” The clinic had already begun to receive dozens of phone calls from fans looking for someone who might understand their shock. Sue approached the whole ordeal with a clinician’s impartiality, focused on her duty to convey resources. Despite the phone calls and the media frenzy and her son’s reaction, she did not understand the magnitude of Cobain’s influence until she arrived at Seattle Center the following morning to find several thousand distraught Nirvana fans waiting for answers. “I had no idea it was going to be that big,” she says. “I saw all those people and all I could think was, ‘Oh fuck. What have I done?’”

I find a few preserved home video clips of the vigil online. One begins with fans scaling the International Fountain—a mainstay from the World’s Fair thirty years earlier. Bodies climb through pressurized streams, turning around to yell and flash their devil-horned fingers to a throng that looks on, holding cheap candles brought from home that drip wax all over their fingers. Somebody holds a burning poster of Cobain over his head. When it starts to droop in flames, hands reach out of the crowd to help prop it up. A couple of girls sit on their boyfriends’ shoulders to see. Other people crouch on the ground in circles, surrounding makeshift shrines of photos and candles, scattered through the crowd like earthbound constellations.

A better quality video, taped from MTV News, is of the vigil’s central event: Courtney Love’s prerecorded reading of Cobain’s suicide note, played through a massive PA system to a motionless crowd. Subtitles overlay fans’ heads, pointed downward at Converse sneakers. “I’m not gonna read you all the note ’cause it’s none of the rest of your fucking business,” Love says. Her voice is raspier than normal, as though filtered through a distortion pedal. “And I don’t really think it takes away his dignity to read this, considering that it’s addressed to most of you. He’s such an asshole. I want you all to say ‘asshole’ really loud.”

The audience pauses for a second—is she serious?—before conceding. The sound of people yelling “ASSHOLE” resonates through the crowd, masked in the video by an extended bleep. The subtitles are censored with ellipses. Her recording waits for their echo to die, and then she begins.

Anyone can now read Cobain’s suicide note. Google showcases a series of image files, JPEGs tinted in different shades of scanner. Some have been rendered artistically with superimposed images of Cobain’s face, or the less tactful splattering of digitally generated blood. If you prefer, you can read the note in print in several Cobain biographies or his published journals. You can study the directions his handwriting slants and the cross-outs and the font size. You can read it over and over, thinking that you are in that moment and might be able to stop what’s coming before you finish.

But in 1994, two days after his body was found, there was no search engine waiting to share the most private moment of his life. There was only his wife, who—like him—understood that generation and foresaw the sea change his death would cause. By reading the note, she offered them access to all of the incomplete answers—that he was overwhelmed by a lack of passion for writing and playing music, that he felt guilty about that emptiness, that he believed himself to be infantile, narcissistic, too sensitive, unappreciative, erratic, hateful. The note was not vengeful; it was hopeless and apologetic. She delivered it with periodically dispersed commentary, as though reading aloud a harsh break-up note she’d found shoved into the slats of her locker. But she also cried, and her sobs were genuine and resonant. Her uninhibited grief transformed his death into something messy and visceral and selfish and ultimately public, offering the several thousand impressionable young adults in Seattle Center the opportunity to identify with her pain, not his.

Love later shows up in person, wearing a flimsy blue bathrobe, her hair dragged up in two dismal and uneven pigtails. MTV is there, waiting to immortalize her sleepless raccoon eyes as she sits on a blanket consoling a few lucky, random fans.

“He doesn’t want to be known for being a drug addict,” she says. “He doesn’t want to be known for being a loser or anything that Rush Limbaugh called him. We all know what he gave to us. Those baby boomers are not supposed to understand.” She holds a lit cigarette and sits with her feet folded under. Three teenage girls wipe tears from tired cheeks.

“If it had happened to me, Kurt would be sitting out here in this park with you, too. He never made himself inaccessible to people… He was so good that way, and no attitude. I wish he had a little more attitude because that might have helped, but what would have helped more than anything was no guns. So, just try and do that, all right?” She hugs the girl in the middle and kisses her cheek. She is talking these girls back from a place where Cobain’s suicide appears reasonable, justifiable, attractive. She is showing them the other side of suicide: the aftermath. She is the aftermath.

That a widow publicly aired the contents of her late husband’s suicide note two days after his body was discovered was revolutionary.

“I give Courtney a ton of credit for why we didn’t have a contagion effect,” says Sue, who took the stage for the Crisis Center shortly after Love’s tape played. “She was enraged, and they needed to see that.” I ask if she’d been worried about the vigil becoming something more romantic, sensationalistic. She shakes her head. “It wasn’t about eulogizing. He was already dead. The message was about preventing further tragedies.”

That Love showed up at Cobain’s vigil decked out in the regalia of mourning and joined the intimate fan circles was somewhat predictable for her; that a widow publicly aired the contents of her late husband’s suicide note two days after his body was discovered was revolutionary. To her, it was an act of authenticity, performed to maintain his accessibility, even in death. To everyone else, it was a way to unroll his suicide like a map, and decide, together, that it was fucked up and not worth emulating. She took from the fans the natural tendency to hide inside suicide’s obscurities, dark corners where romance grows like moss up lightless cavern walls. “Something good can come out of Kurt’s death,” she tells those three girls. “I don’t know what it is yet, but something good can.”

Perhaps that something was a milestone in suicide prevention. But the question is not whether Cobain’s suicide influenced the future; the question is whether a similar future would have happened without it. Suicide is not contagious; it is chemistry. Remove Cobain from the teenage suicides of that time, and what is left? Sadness, alienation, adolescence, shotguns—a series of reagents poised to chemically react. Cobain’s death was only a catalyst, a free agent that cameoed, triggering a few inevitable tragedies. When we imagine a world in which that catalyst had not materialized and things had ended differently, we overlook the possibility that we are all the sum of unfortunate coincidences.

Candace Opper lives and writes in Portland, Oregon. Her work has appeared in Brevity, Bitch Magazine, and various publications put forth by the American Association of Suicidology. She is the media program director for the nonprofit Late Night Library and is currently at work on a book about suicide and the ways we give it meaning.

To contact Guernica or Candace Opper, please write here.