It was in April of 1996, just a few weeks shy of my college graduation, that my parents bought me Infinite Jest as a birthday gift. One of several books I received for the occasion, the novel stood apart from the stack of others first for its brick-like heft, then for its at once generic and serenely singular cover, those languorous waves of downy cumulous clouds drifting over an obscured cerulean. This was right about the height of the swirling buildup around both the author and his book, shortly after Newsday’s heroic heralding of “the next heavyweight of American fiction” and Michiko Kakutani’s proclaiming him a virtuoso “who can seemingly do anything,” when you could spot that big blue tome in almost any downtown New York café, when you were bound to see standing straphangers clutching it under arm on their tired ride home or buried in its footnoted depth if they were lucky enough to grab a seat. David Foster Wallace was everywhere, or so it seemed to me.

Though I have always prided myself on resisting the temptation to succumb to the whims and wheels of pop culture’s tastes of the moment, there was something about this book and this writer that drew me in, something more than their ubiquity. A couple of years earlier I had read the stories in his first collection, Girl with Curious Hair, and had found them good, solid pieces of short fiction, but nothing remarkable, nothing worthy of the praise and publicity surrounding his current work. So it was with a kind of reserved and suspicious interest that I approached Infinite Jest, hoping for more than the hype and frankly expecting a little less.

Two novels (and agents) into my writing career, a shoebox of rejection letters already collected, I wrote to Wallace in the fall of 2004, care of Little, Brown, asking him to read the manuscript of my second novel, not sure exactly what I was hoping for.

The experience of reading this novel was nearly mystical for me, as close to epiphany as anything I have encountered. It changed my life, literally, providing me with the final thrust I was waiting for, that extra push toward what I knew I wanted to do since I was old enough to scribble out five-page Dracula “novels” on yellow legal pads in the back room of my father’s Brooklyn law office, a vision that had somehow taken a turn through high school post-punk bands and death metal solo projects, through four years of undergraduate philosophy and through potentially following my father’s jural footsteps. Once I finished reading Infinite Jest, I distinctly remember thinking that the highest achievement of a lifetime would be to produce something so magnificent and awesome and beautiful. And the fact that this epic and accessible book was written by a guy little more than a dozen years my senior, who was speaking to me and my generation in ways few others even attempted to, gave renewed breath to a flagging faith in the power of fiction to be not just relevant but vital. Wallace’s magnum opus connected viscerally with Emerson’s maxim: “The foregoing generations beheld God and nature face to face; we, through their eyes. Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe?” It proved exactly what I needed to convince me to abandon my plans for grad school in philosophy in order to pursue the writing life, in order to become, one day, something resembling David Foster Wallace. Sixteen years later, though I do live a writer’s life of sorts, it is nothing remotely close to the one I’d hoped for when I had finished reading Infinite Jest, described in so many colorful features as the venerated young author being chauffeured from one packed reading to the next, from literary launch party to high-profile interview to signings at bookstores spilling over with adoring fans, several of which I attended. Which brings me to the epicenter of this reflection: my brief correspondence with the man who had borne an unwitting influence on my life.

Two novels (and agents) into my writing career, a shoebox of rejection letters already collected, I wrote to Wallace in the fall of 2004, care of Little, Brown, asking him to read the manuscript of my second novel. At that time I was just getting over the foolish impression that the hardest part of the writing life would be the actual writing, never having imagined how Sisyphean the road to publication would be, daring the buoyant young novelist to persist in his idiot quest so that he may be struck down at every attempt.

My letter began with honest praise, explaining the kind of influence his books exerted over me, how I felt upon reading Infinite Jest and how said experience propelled me into serious fiction writing and thus landed me in the quagmire I now found myself, perhaps in retrospect trying to impart a bit of guilt onto the writer for the unintended impetus that had led me to this impasse. Then I informed him of my situation, letting him in on the awful obstacles to publication I had theretofore encountered, and humbly requesting that he permit me to send him my novel. It seemed like a reasonable request at the time. I didn’t expect him to drop everything, read my book and proclaim it a work of unsurpassable genius; I didn’t expect a close reading with detailed editorial suggestions and lengthy comments. I suppose all I was hoping for was that my writing be read by David Foster Wallace, which, at the risk of hyperbole, was somewhat akin to a zealot’s hope that his prayers find their way into the hands of a worshiped but otherwise uninterested god. Mostly, I was feeling down and desperate, and reaching out to the man who had greatly inspired my failing quest just felt like something I should do, if for nothing else than for having done so.

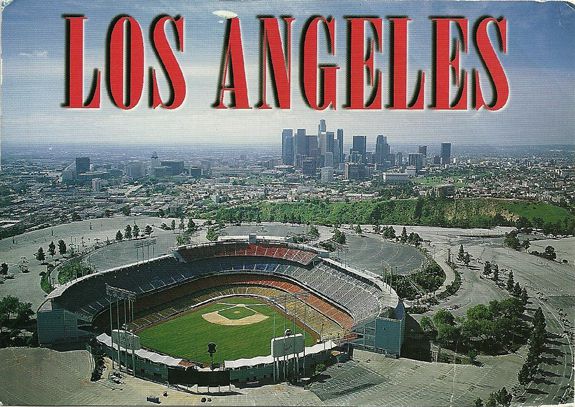

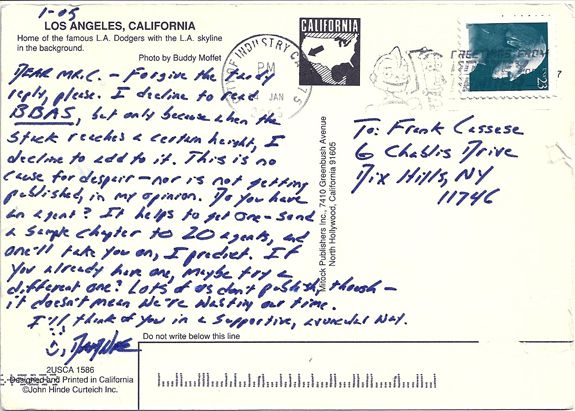

Several months later I received a postcard in the mail, a slightly tattered 4×6 of Dodger Stadium, with Los Angeles smeared across the top in imposing red capitals and a smoggy scattered skyline in the background. By this time I had all but forgotten my letter. I didn’t know anyone in LA, but figured a friend was traveling and decided to drop a line, so I lowered my eyes past the rows of neatly lined and evenly spaced blue ink print to the signature, which was illegible, next to an adumbrated smiley face.

A couple of lines into the text, I realized I had received a response from David Foster Wallace, and as adolescent as it may sound, my heart rate did quicken. But the excitement was tamped by his declining to read my novel, “but only because when the stack reaches a certain height, I decline to add to it.” (So I was not unique in my request!) By the time I finished, I was somewhere between disappointment and anger; not only had he refused to read my book (the nerve!), but he went on to say how this was “no cause for despair,” and that “lots of us don’t publish… it doesn’t mean we’re wasting our time.” He suggested I send a sample chapter to twenty agents, or, if I already had an agent, maybe I should try a new one, and he finished by promising to think of me “in a supportive, avuncular way.”

I’d never met David Foster Wallace. I’d never talked to him. I’d seen him at a few readings and that was the extent of it. Except that I had a hundred or so words of the millions he had written, that were meant only for me.

I stared at the card, flipping it over to study the empty stadium and surrounding cityscape. Why did he choose to send me a postcard? Simply because it’s a few cents cheaper than mailing a letter in an envelope? Was it just sitting around when he was looking for something to write on? Does he buy stacks of these postcards for the express purpose of responding to random fans? And worse, does he write this same prepared response to every letter? Then I went back and reread the words. That he could callously slap down my heartfelt entreaty—especially when couched in such genuine admiration—and tell me not to be concerned about my failure to publish, was tantamount to declaring my life’s ambition little more than a weekend hobby. That he could compound the insult by suggesting I send a sample chapter to a handful of agents, something any hopeful writer who consults how-to books on publishing knows enough to do (and thus has already learned from painful schooling that getting picked from the slush by a reputable agent is about as likely as hitting the bull’s-eye in a drunken game of darts), felt painfully patronizing. And that he could finish by claiming he’d think of me in such an encouraging manner, as though a man of his philosophical sophistication truly believed that positive thoughts had any practical sway over the course of events (or that he would even think once of our brief correspondence after the card was in the mail), was just plain dishonest. Not to mention infuriating.

It might have been better, I thought, not to have heard back from him at all. Such a disillusioning response from a major influence seemed enough to founder the entire enterprise, to embitter my ambitions. I stuck the card somewhere in the middle of my copy of Infinite Jest and vowed never to look at either again. I might even have made a silent pact with myself never to read any of his work. Though, when Consider the Lobster came out eleven months later, my ire had sufficiently shrunken enough for me to buy the book upon release. But however healed the initial hurt, I would not let go of the fact that I could now add a rejection from David Foster Wallace to my shoebox of form letters from agents and editors.

Time passed, more rejections came (along with a few happy acceptances), and I rarely if ever thought about the postcard. It was not until more than three and a half years later, in September 2008, when the awful news was delivered, that I revisited our correspondence.

Greatness generates a sense of familiarity where there is otherwise alienation, and we cannot help but feel a primal connection with its creator. Still, I’d never met David Foster Wallace. I’d never talked to him. I’d seen him at a few readings and that was the extent of it. Except that I had a hundred or so words of the millions he had written, that were meant only for me.

Let me just say that his death cast a serious pall over my mood for weeks and hindered my writing for the better part of six months. If this man, whose genius was in so many ways unparalleled, could not find enough solace in his work and success to fend off the demons of life, how could I, who had achieved so much less, justify continuance? I realize medical and psychological issues were at play. I understand that clinical depression is a chemical thing that I—a mere melancholic, a chronic depressive, rather than clinically diagnosed—cannot wholly relate to. I realize medication was a factor in his life and death, and that regardless of all this, one can never know the depth of another’s suffering, let alone a public figure with whom my only contact was a long-neglected postcard. Nevertheless, if David Foster Wallace represented everything I wanted to be, and all that wasn’t sufficient to quell his torment at least enough to keep him in the world, what the hell was I trying for? If the adoration of the masses was insufficient, and the respect of his peers and praise of his predecessors was ultimately unfulfilling, if nothing about his extraordinary accomplishments was enough to fend off the demons that were calling him to quit, then what hope was there for someone like me? What succor, even in success? Why bother struggling to reach the peak when the only thing you can do from there is fall?

He was telling me what I already knew but had forgotten over the long years of struggling for acceptance and societal validation, that creation is its own reward, that the project of writing is its own gift, provides its own consolation, which no degree of outward acceptance or rejection can touch, if properly appreciated.

In the wake of his suicide, the postcard took on new significance, and I saw his message to me in a different light, tinted by his departure from the world and particularly by the way he enacted this departure. Rereading his words, they seemed neither condescending nor dismissive, and though I still regret his declining my appeal (even more so now that he will never read my work), the immense outpouring of public sentiment over his death made me realize just how hugely popular he was, and that my request was simply one of many, many similar others. The mere fact that he took the time to personally respond to me was a courtesy I was now ashamed to have not accorded more value. But beyond the surface reevaluations, there is the deeper and more meaningful interpretation of his sentiments, which show a serious compassion for an unknown and struggling writer. There is a sincere gentleness in the way he assured me that his refusal was “no cause for despair—nor is not getting published,” that though my disappointment was one with which he could sympathize (though surely not empathize, with his prodigious record of publication from a relatively early age), it should not cause me much grief; it was not the kind of despair that truly merits the label, the kind that he surely knew, that we all know to degrees. There is frustration. There is suffering. And then there is despair.

Then there is his use of the pronouns we and us “Lots of us don’t publish, though—it doesn’t mean we’re wasting our time.” What I had first taken as aloof and supercilious, an arrogant condescension and insensitive refusal to lower the ladder from one who has reached the dazzling heights to another who is stranded in the depths, I now saw as both an identification with my plight and a coded missive that publication was not the promised land I thought it was. I choose to believe that he was including me in his use of we and us, and that he genuinely drew little distinction between those of us who had found publication, who were graced with the approbation of the world, and we who were still toiling in the darkness.

I think Wallace truly believed that we are not wasting our time, even if our words are never seen by the world at large. The world has never been the best judge. It has never equitably distributed recognition to all those deserving. It sometimes gets it right, as I think it did with Wallace, but more often than not it fails us. So what he was telling me was not that publishing is not a good thing, but that it isn’t everything. It does not bestow value or worth on one’s work or on one’s self. It does not make a published book better or worse than an unpublished one. And while the failure to achieve it may be no cause for despair, its attainment is certainly no cure. He was telling me what I already knew but had forgotten during my struggle for acceptance and societal validation, that creation is its own reward, that the project of writing is its own gift, provides its own consolation. Half a century before in The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus claimed that despite the absurdly futile and hopeless task with which the condemned king was punished by the gods, “the struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

I cannot imagine David Foster Wallace happy, but this is less a flaw in the man as in the common human conception of happiness. Surely the idea of happiness as a consistent and lasting state of contentment is as much a myth as our boulder-pushing king. But if there is any shred of truth to the myth, any hint to the real existence of some form of happiness, my letter from Wallace forces me to remember that most meaningful of clues, that for me as a writer, for us as artists, the only hope for any kind of happiness, it is not to be sought in others’ veneration of our work or in the public display of our talents. It is in the act of creation itself, in those ineffable moments of quiet and solitude when we commune with what is most real: ourselves, and the world that exists within. That is the world that matters. “The rest is silence.”

Now almost eight years old, a bit more ragged at the edges and yellow with age, the postcard from David Foster Wallace remains a treasured object. Not only because it came to me from one so near the peak in my pantheon of esteemed figures, but because of how its meaning has changed over the years. I don’t look at it often, but when I hold it between my fingers and read that small scrupulous print, I experience a sad reassurance in both the value and ultimate futility of writing. And yet above all it encourages me to go on, to continue to create. It inspires me to find comfort and, yes, moments of happiness, and helps me to maintain contact with those reasons and feelings that made me want to write in the first place. William H. Gass addressed “the wretched writer” who has felt the weight of the world leaning on his soul, “give up the blue things of this world for the words which say them.” I try to do what these men tell me, to abandon the crude and coarse world at large and inhabit the one of my own words, the one I have created by and for myself. And it feels good. It feels right. I only wish David Foster Wallace, with all his unmatched ability to create such worlds for himself, were still here, somewhere in mine.

Born in New York City and raised on Long Island, Frank Cassese finds his writing shaped by the frenetic influence of urban life and the languid reality of the suburbs. After graduating with a degree in philosophy, he lived and worked in France for some time before returning to New York, where he received an MA in creative writing from The City College. He has published a short story in the literary magazine The Body Divided, as well as an article in the French journal Revue de littérature contemporaine et expérimentale, and has collaborated with the conceptual artist Lee Walton on the project Come on Pilgrim. Frank is the author of several novels and is currently at work on a new book on the Bowery.