So we should ask Mohammed Al-Durra. He isn’t dead again.

Recall his face. Even from a government one of the chief exports of which is images of screaming children, his was particularly choice, tucked behind his desperate father, pinned by fire. Until Israeli bullets visit them and they both go limp. He for good. Pour encourager les autres.

Now, though, thirteen years after he was shot on camera—one year more than he lived—he has been brought back to life. But wait before you celebrate: there are no very clear protocols for this strange paper resurrection. Mohammed Al-Durra is a bureaucratic Lazarus. After a long official investigation, by the power vested in it, the Israeli government has declared him not dead. He did not die.

There was another boy at the hospital, there were no injuries, it was a trick. A blood libel to suggest he was killed by Israelis, the same day as were Nizar Aida and Khaled al-Bazyan, one day before Muhammad al-Abasi and Sara Hasan and Samer Tubanja and Sami al-Taramsi and Hussam Bakhit and Iyad al-Khashishi, two before Wael Qatawi and Aseel Asleh, three before Hussam al-Hamshari and Amr al-Rifai, but stop because listing killed children takes a long time. Keep his name out of that file.

Jamal Al-Durra will open his son’s grave. “Is that enough?” he asks with a unique exhaustion. “To prove that this thing we saw happen happened, that the boy we saw die died?”

The task is complete. Wheels are spinning. A new pass law. The IDF has been sent, a checkpoint set up at the border of the land of the dead. And Mohammed Al-Durra has been hard-stopped by the guards because he does not carry the right papers.

Undesirable life is ended, and unauthorized death is banned. Where is Mohammed to go now, the victim of this necrocide, this murder of the killed?

Between wire runnels, tangled chains, cages, again. Again, again. Maybe that’s where the shot-again newly unkilled boy will kick his heels. A purgatory not for the unshriven but for the troublesomely Arab, for the death-contested.

In Jerusalem, the government decrees that Palestinian deceased sublimate after seven years, to be absent, to go to the nothingness that their recalcitrant bodies, living then dead, resist. They absent themselves finally from the real estate they hog, and at last it can be where a cable car touches down. It can be a foundation for engines.

“Peace is a corrupt business in Palestine,” he says.

Driving in from Allenby, the rock gorge has been hacked ruthlessly out of the mountains and protruding from one part is a jagged fringe of metal where some once-submerged and hidden corridor has been exposed and left to weather and dangle from its housing.

Yes, we know the holy land is now a land of holes, and lines, a freakshow of topography gone utterly and hideously mad, that the war against Palestinians is also a war against everyday life, against human space, a war waged with all expected hardware, with violent weaponized absurdism, with tons and tons of concrete and girders. This is truism, and/but true.

“Settler” is an odd term for these vectors of the unsettling, government-sponsored agents of government-desired permanent crisis, for whom stability and everyday life is anathema to be fought unstintingly, with bullets and beatdowns and strategies of berserker spite.

The low mesh sky of Al-Khalil market is pelted with its own grotesque microclimate. Hebron. These low clouds are piss-bottles, concrete slabs, storms of trash, a suspended weather of race-hate. Stand between stallholders whose dogged sales patter become heroics in the shadows of bags of shit, stand by a ledge where a ginger kitten picks intrepidly through razor-wire and look up. There’s something brewing.

They used to play games, she explains. She and her friends were told to behave or else the Settler would come and get them. They knew his name, they knew he had a wooden leg, they convinced each other and themselves that they could hear him coming. Clack drag clack drag clack. They knew the scary rhythms and covered their mouths. Those sounds he made. They pantomimed the terrible things he would do if he caught them. Much later, she read a newspaper and of course he had been real.

In Jerusalem, the flags on the stolen house metastasize. They jut vertically, of course, and horizontally, but then they protrude at all ludicrous angles in between, as if any sough of Palestinian air unruffled by the white and blue is an outrage. They must not leave a breath unclaimed.

There is a mannequin in Al-Khalil, in the market, a plastic woman with very pale skin and outdated hair, modeling a long black dress with red trim. She stares stupidly ahead, as if she would like you to join her in ignoring the hole in her forehead, almost exactly in the center, only a little to the right, where her eyebrow ends. It is just like the hole a bullet would make if this placid woman had been targeted by a sniper. Move to the side: the right rear of her head is gone. Yes, that’s where the exit wound would be, and it would pass through much like that, yes, leaving a hole like that one, shaped, I swear to God, like that one; like something big and familiar.

The young Jewish woman turns and gasps as you follow her into Qalandiya, through steel runs that are too narrow. She says “I can’t believe this was designed by people with these memories.” An entrance to discourage entrance in the first place, but, like a pitcher plant, to make it impossible, once entered, to change your mind.

There’s a place where the wall incorporates a house. If you hang a picture up you decorate the inside of that dorsal ridge, the scales of that rising concrete animal.

And in its wedge of shadow the long stupid zigzag of the checkpoint between Bethlehem and Jerusalem is indicated with a sign, there on the Bethlehem side. Entrance, it says, white on green, and points to the cattle run. Inside are all the ranks of places to wait, the revolving grinder doors, green lights that may or may not mean a thing, the conveyor belts and metal detectors and soldiers and more doors, more metal striae, more gates.

Finally, for those who emerge on the city side, who come out in the sun and go on, there is a sign they, you, we have seen before. White on green, pointing back the way just come.

Entrance, it says. Just like its counterpart on the other side of a line of division, a non-place.

No exit is marked.

The arrows both point in. Straight towards each other. The logic of the worst dream. They beckon. They are for those who will always be outside, and they point the way to go. Enter to discover you’ve gone the only way, exactly the wrong way.

Entrance: a serious injunction. A demand. Their pointing is the pull of a black hole. Their directions meet at a horizon. Was it ever a gateway between? A checkpoint become its own end.

This is the plan. The arrows point force at each other like the walls of a trash compactor. Obey them and people will slowly approach each other and edge closer and closer from each side and meet at last, head on like women and men walking into their own reflections, but mashed instead into each other, crushed into a mass.

Entrance, entrance. These directions are peremptory, their signwriters voracious, insisting on obedience everywhere, impatient for the whole of Palestine to take its turn, the turn demanded, until every woman and man and child is waiting on one side or the other in long long lines, snaking across their land like the wall, shuffling into Israel’s eternal and undivided capital, CheckPointVille, at which all compasses point, towards which winds go, and there at the end of the metal run the huge, docile, cow-like crowds will in this fond, politicidal, necrocidal, psyche-cidal fantasy, meet and keep taking tiny steps forward held up by the narrowness of the walls until they press into each others’ substance and their skins breach and their bones mix and they fall into gravity one with the next. Palestine as plasma. Amorphous. Amoebal. Condensed. Women and men at point zero. Shrunken by weight, eaten and not digested. An infinite mass, in an infinitely small space.

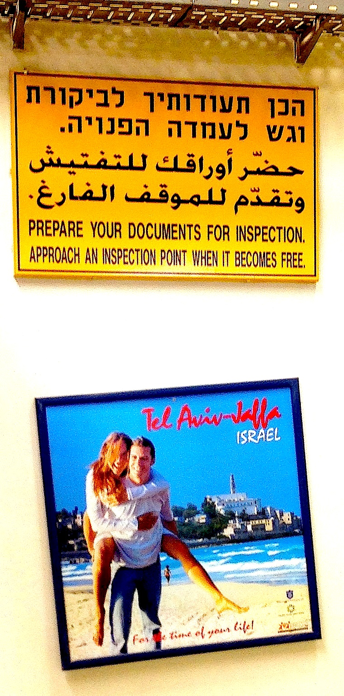

In the bowels of that hangar where the lines of those arrows meet are advertisements. “Israel,” one says in that no-place, on the line in the sand, “where it’s vacation all year round.”

Please understand that there is nothing unthinking about that joke, that these are exactly the posters a Palestinian is supposed to see at this point, that this is information she needs, now move on, keep going on this time out of time, time off, this vacation you have been given on the sand. You are beached. Get out.

There is no out. The signs are very clear. Everything is an entrance, and it all leads here.

In Hebrew, Arabic, and English, in black on yellow: “Prepare your documents for inspection.” And below that another of the posters. Under the smiling, piggy-backing couple: “Israel: For the time of your life.”

It’s not intended to be a surprise. So that is the plan and there it is. Here is time, and your life. Have everyone shuffle forward for all time on this bad, bad holiday, into this eternity.

You are supposed to follow the signs. Here is the idea. It will be explained again, as often as it takes. The end is not to be three strangers in a room alone but a nation, two near-unending lines of broken living and the authorized dead, ordered forward and pushing and pushed and becoming nothing. What is lawfully inscribed here is not “No Exit”: it is “Entrance—Entrance.”

China Miéville is the author of nine novels and two books of non-fiction, as well as comic books and many short stories. Miéville has won the Hugo, World Fantasy and Arthur C. Clarke Award (three times). He visited the West Bank as a guest of the Palestine Festival of Literature (PalFest), where this piece was written and performed in Nablus. He lives in London.