T

he prisoner raises his feet and pulls at his chain, slowly, cautiously. The chain rattles softly, then tightens, forming a “V” between the prisoner’s ankles and a metal ring bolted to the floor. Maybe it’s a coincidence. Maybe he consciously turns the chain into a victory sign. His eyes do not tell. The truth is hard to see in this room, where Combatant Status Review Tribunals are held. It’s a blurred sphere of maybes.

The prisoner is sitting on a white plastic chair that his captors consider the only piece of furniture in this room he won’t be able to turn into a weapon. He’s holding the manuscript of his defense in his hands, but he can’t move them—his wrists are shackled. The handcuffs are linked to a chain that wraps tightly around his belly, fixing his hands in front of his navel, forcing him into a posture of submission. He lowers his head and looks at the manuscript, moving his lips as if whispering a prayer.

Three men with shaved faces and shorn heads enter the room with fast, even steps, walking in synchrony. Holding black folders in their left hands, they line up in front of a large American flag, framed like a painting. A military guard, his voice booming across the room, orders everyone to rise. The prisoner gets up, and the “V” collapses between his feet.

The room behind door 7E is a hermetic place, built for the system operating within it. No daylight penetrates its windowless walls, no warm air, no lawyer, no judge. It is a rectangle outside the law, an American place outside America.

The prisoner smiles.

It’s a rare day in Guantánamo, a strange day. The man at the end of the chain has come to talk. He is willing to speak about a man he met in Afghanistan, in the White Mountains of which Tora Bora forms a part. He does not say the man’s name; he only calls him UBL. It sounds like a code, a rank. The letters are the initials of Usama bin Laden.

Theoretically, Room 7E could be a place of hope, could offer a chance at freedom. Once a year the prisoners are allowed to stand here before a military tribunal and make a case for why they are no danger to America, why America should let them go. Many of them do not appear. They think it’s useless.

Yasser bin Talal al-Zahrani, Mani Shaman Turki al-Habardi al-Utaybi, and Salah Ali Abdullah Ahmed al-Salami never set foot in this room. They remained in their cells, silent. They no longer believed in life after Guantánamo. They resisted a system that kept them in the dark about their future. They refused to defend themselves against mere accusations.

They were three proud Arab men, and they despised the America they came to know in Guantánamo. They didn’t smile like the man at the end of the chain. They didn’t offer themselves as spies, hoping that America would let them go.

At some point during their captivity, these three men began to retreat. They no longer touched the food the guards pushed through the holes in the doors of their cells. Their bodies dwindled. Their lives hung on thin yellow tubes shoved down their nostrils each morning to let a nutrient fluid drip into their stomachs. In their minds, nothing changed. They didn’t want to stay, and one night, on June 9, 2006, they decided to leave Guantánamo. They climbed on top of the sinks in their cells and hanged themselves.

In the Pentagon’s view, the men hanging from the walls of their cells were assassins whose suicides were attacks on America. The Pentagon struck back.

The story of the lives and deaths of these prisoners is an odyssey of three young men who left for Afghanistan and ended up in Cuba. It is the story of a war against a terror that is difficult to define, a war that the United States government wages even in the cells of its prisoners. It is about a place, Camp Delta, that exposes the asymmetry of this war, and it leads to the front lines—and the American lawyers standing between them, struggling to defend presumed enemies of their country. It is the story of the internal and external battle over Guantánamo.

Nobody but the dead knows the whole truth. But there are places where the story can be pieced together. There are files and letters, people who distinctly remember these prisoners. There are places where the strands of this story intersect. A law firm in Washington. A mosque in London. A living room in North Carolina. A cell in Guantánamo.

Yasser bin Talal al-Zahrani is sixteen years old when he says good-bye to his father in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. It is the summer of 2001. Yasser has just completed eleventh grade in high school. He is one of the best students in his class, strong-willed and hungry for knowledge, and he’s looking for a new challenge. He says he wants to go to Dubai, the city of opportunity, to study English and computer science. But several weeks after leaving Mecca, Yasser calls his father from the Pakistan-Afghanistan border. In New York the towers have fallen, and in Afghanistan the U.S. attack on the Taliban has begun. Yasser tells his father that he wants to join a charity and help the people of Afghanistan. He says he owes it to his Muslim brothers.

A few days later, Yasser calls again. He tells his mother that he is getting ready go to an area where he won’t be able to make phone calls, and he wants to say good-bye. He doesn’t tell her where he will be going, and his mother doesn’t ask. She wishes that Allah might protect him. It is the last time she hears his voice.

Mani Shaman Turki al-Habardi al-Utaybi is born in the same country as Yasser, but their lives have little in common. He grows up in a cocoon of prosperity, enjoying parties and indulging himself in forbidden pleasures. Sometimes his way of life puts him in conflict with the enforcers of Saudi Arabia’s moral code, but his family’s ties to government officials shield him from punishment.

Sometime around September 11, 2001, Utaybi breaks with his spoiled life. He joins Tablighi Jamaat, a group of Muslim missionaries. It is one of the largest and most conservative Muslim organizations, a globe-spanning network of proselytizers. From New York to Karachi, the group approaches young men at mosques and universities and tries to lead them to lives governed by Islam. Utaybi follows the call and leaves for Pakistan.

Salah Ali Abdullah Ahmad al-Salami has been following the rules of the Qur’an since childhood. He lives with his family in Ta’izz, Yemen’s third-largest city, near the Red Sea. He reads the Qur’an with such devotion that, at an unusually young age, he becomes a haafidh, a scholar who remembers the whole book of the Prophet Muhammad. He also follows Islamic tradition in matters of love. The woman he marries is chosen by his family.

The Pentagon describes only in vague terms where and why it captured the men. There is just one sheet of paper. It reads like a final report, as though all questions have been answered.

Salami’s faith is his navigation system, the point of reference for his view of the world. Sometime in 2001 he goes to Pakistan. He travels to Faisalabad, a city close to Lahore, in search of the deeper meaning of his faith. There, he lives with several other young men in a house and studies the Qur’an.

Salami, Zahrani, and Utaybi’s paths do not cross in Pakistan, but it is the country where all of them stop on their way to Afghanistan, like a base camp. It’s unclear if they actually cross the border and enter the land of the Taliban. Their traces end in Pakistan.

The Pentagon describes only in vague terms where and why it captured the men. There is just one sheet of paper, a press release that summarizes the lives of the prisoners in a few paragraphs. It is the only document the U.S. government publishes about the suicides, hours after the men hanged themselves. It reads like a final report, as though all questions have been answered.

The underage Zahrani is described in the press release as a “frontline fighter for the Taliban” who organized the purchase of weapons. He is accused of having been among the prisoners who began a bloody uprising in the Mazar-e-Sharif prison in northern Afghanistan, during which CIA officer Johnny Micheal Spann, who found John Walker Lindh, later know as the “American Taliban,” was killed.

Of Utaybi, the press release says only that he was a member of a terrorist group, a “second-tier recruiting organization” of Al Qaeda. The organization the Pentagon is referring to is Tablighi Jamaat, the group of Muslim missionaries Utaybi joined in Saudi Arabia. Tablighi Jamaat is not banned in the United States and not listed as a terrorist organization.

Salami is described by the Pentagon as the most dangerous of the three prisoners, a “mid- to high-level Al Qaeda operative” with “close ties to Abu Zubaydah.” Zubaydah, who was later captured, is accused of being a member of Al Qaeda’s leadership and, together with Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, one of the masterminds behind the September 11 attacks. The Pentagon does not say where it captured Salami, but it inadvertently allowed another prisoner in Guantánamo to tell the story. It can be found in the transcripts of the Combatant Status Review Tribunals which decide whether a prisoner is an enemy combatant. The Pentagon did not want to publish the transcripts, but was ordered to release them through Freedom of Information Act litigation.

Many of the transcripts can be found online, some at a Department of Defense website and others in a database maintained by the New York Times. It is the virtual front where America defends itself early in the War on Terror. One can search for prisoners and read what they said at their tribunals. But the prisoners do not have names in the transcripts, only three-digit “internment serial numbers.” They are as faceless as the tribunal officers, whose names are blacked out.

There is no transcript of a hearing for Salami on either site. But his name appears in the transcript of the hearing of prisoner 688, who talks about meeting Salami in Faisalabad. Prisoner 688 is also from Yemen, and claims to have gone to Pakistan to sell textiles. On a street in Faisalabad, he hears Salami speak Arabic and introduces himself. He tells him that his Pakistani visa has expired, and Salami promises to help. He says he knows people with government connections who could solve the problem.

Salami offers the man a place to stay at the house where he studies the Qur’an, and the man follows him. Two weeks later, Pakistani security forces, accompanied by two Americans, raid the house and arrest all the men inside.

The Pakistanis take Salami and the other man to Lahore, where they are interrogated for a week by Americans who do not wear uniforms and do not identify themselves. From Lahore, they are moved to Islamabad and then flown, in an American military plane, to Afghanistan, first to Bagram and later to Kandahar. Eventually, Salami is led up a ramp, into the belly of another plane. It is the last stage of his long journey into death.

More details about the captures of the three men became public when, in 2010, secret Pentagon files were turned over to WikiLeaks. According to these files, the U.S. believed that the guesthouse where Salami was apprehended had links to Al Qaeda and that Salami lied about being a religious student. Other detainees claimed they had seen him in training camps with members of Al Qaeda.

Utaybi is described in the files as having been arrested with four other men, all hiding under burqas, at a checkpoint in Pakistan. One of the men had supposedly been to a terrorist training camp, and Utaybi was said to be carrying a false Yemeni passport.

Zahrani, according to the files, admitted that he had gone to Afghanistan to be a jihadist. In Guantánamo he supposedly once shouted, laughingly, “9/11 you not forget” at a prison staff member.

Salami, Zahrani, and Utaybi are captured at different times and locations, but they end up in the same place. One day, their faces and heads are shaved. They are put into diapers and bright orange overalls. Headphones that silence the world around them are put over their ears. Their mouths are covered with sterile masks. Black cloth bags are pulled over their heads. They look like men on their way to the gallows. And then they are chained to the floor of a plane, like pieces of cargo.

They leave Afghanistan eight thousand miles behind, freezing on the metal floor. Then they walk out of the plane and into a burning heat. They are in Guantánamo.

A few reporters are allowed to watch the arrival of the first prisoners from a distance, in January 2002. They witness a performance. The prisoners are paraded out of the plane, surrounded by Marines screaming at them. Taking small steps, they stumble as the chains tighten between their feet. When they finally reach the tarmac, some fall to their knees. Maybe they are exhausted, maybe they want to pray.

The vehicles transporting the prisoners turn right shortly before the columns, then stop in front of a labyrinth of metal fences and barbed wire. The prisoners have reached their destination.

Zahrani, Utaybi, and Salami probably do not know where they are. They are driven north on Sherman Avenue, to a hill from where one can see the other, sovereign Cuba. This is where the “No Salute Area” begins. Signposts remind the soldiers that they must not salute each other here, to keep the Cubans who might be watching from figuring out the camp’s command structure. Two columns wrapped in barbed wire rise to the left and right of the road, a message sprayed on each one. The messages refer to the Cuba beyond the columns, but they could be a greeting for the prisoners. “Enter if you dare,” it reads on the left, “Get out if you can,” on the right.

The vehicles transporting the prisoners turn right shortly before the columns, then stop in front of a labyrinth of metal fences and barbed wire. The prisoners have reached their destination. They are in Camp X-Ray. The camp was given its name because the cells have no walls, only chain-link fences. It is a place where America transilluminates its prisoners.

From the outside, the camp looks like a giant stage, an installation where the prisoners are put on display. Zahrani, Utaybi, and Salami pace back and forth in their cells like animals in cages. The tin roofs over their heads only protect them when the sun is at its peak and the rain falls vertically. They sleep on the concrete floor as spiders, scorpions, lizards, and rats crawl into their cells. They have no toilets, only buckets to relieve themselves.

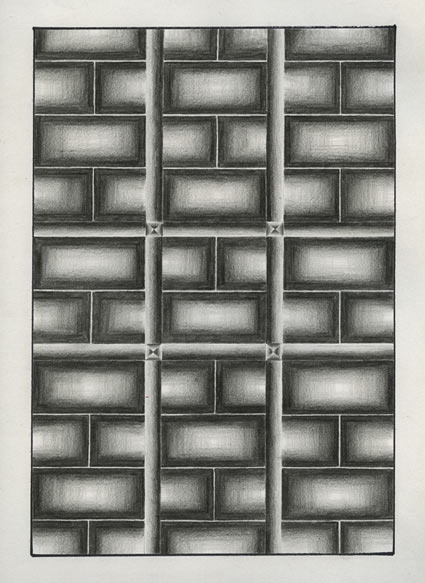

Three months after their arrival, the prisoners leave Camp X-Ray. They are transferred from the inner part of Guantánamo Bay to a location close to the Caribbean coast where the Pentagon has built a new camp. Camp Delta is an interlocked, rectangular structure where the prisoners are moved around like figures on a chessboard. They are sent traveling on an endless journey through the camp’s inner world, through security levels and interrogation rooms, from solitary confinement to the hospital.

The prisoners are measured and classified depending on their willingness to talk and obey. They are divided into a three-class society and dressed accordingly, to fit the camp’s color code: white for the willing, brown for the obedient, orange for the dangerous.

Camp 1, where the obedient are held, is the core of Camp Delta—a square structure where the cellblocks stand next to each other like row houses. This is where Zahrani, Utaybi, and Salami get to know each other. The wire-mesh walls are less transparent than the chain-link fences at Camp X-Ray, but the prisoners can see and hear their immediate neighbors. They can whisper to each other and send messages from one end of the cellblock to the other.

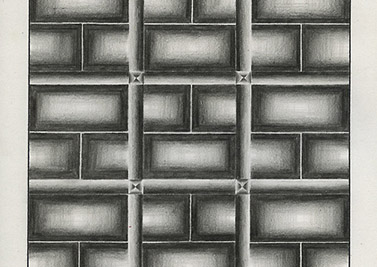

The cellblocks in Camp 1 are made of steel, welded together into rectangular structures facing each other. The guards walk down the corridor in the middle as if on the deck of a cargo ship. The prisoners can hear them coming before they see them; the sound of their boots on the metal floor announces their arrival. There are twenty-four cells on each side of the corridor, each with the exact same measurements: six feet and seven inches wide, eight feet long.

Zahrani, Utaybi, and Salami are waiting in the hollowness of their cells. There is nothing to hold onto—no chair, no table, nothing to hurt themselves or the guards with. There is a sink in the corner, next to the crevice in the floor where they squat to relieve themselves. The sink is made of steel and welded to the wall; it looks shrunken, small and low, as if built for children. The prisoners have to stoop to use it, but it’s a convenient height for washing their feet before prayer. Perhaps it is during one of those moments, when they wash their feet, that they realize that the sink could be used as something else: a stair, a pedestal.

They never know how long they will stay in their cells. It is part of the system—an uncertainty designed to prevent or destroy friendships. Guantánamo is a state of suspense.

They have time to think. They lie on their beds—metal plates jutting out from the walls like shelves—staring at the black arrow painted on the foot end that gives them some sense of direction. It points to Mecca.

They never know how long they will stay in their cells. Sometimes they are transferred to different cells after a few hours, sometimes after days, sometimes after weeks. Sometimes within the same block, sometimes to a different block. Sometimes during the day, sometimes during the night. It is part of the system—an uncertainty designed to prevent or destroy friendships. Guantánamo is a state of suspense.

At some point, Tarek Dergoul is transferred to the cell next to Utaybi’s. He is the son of Moroccan parents and lived in London. Shortly before the United States attacked, Dergoul went to Afghanistan to buy houses from people who abandoned them in fear of the expected onslaught. He believed that enough houses would remain standing after the war, and that he would be able to sell them at a profit. But he miscalculated. He was hit by shrapnel and lost his left arm when one of the houses was bombed. Fighters for the Northern Alliance found him in the rubble and sold him for $5,000 to the Americans, and his journey to Guantánamo began.

For almost three weeks, Dergoul and Utaybi are separated only by a wire-mesh wall. They can’t do anything the other doesn’t see or hear. Utaybi is a man without a face; no photograph of him was ever released. Dergoul describes him as slightly taller than himself, about five foot ten, with dark, almost black skin, his face slim and elongated. “Mani was very thin,” Dergoul says. “When he wasn’t wearing a shirt, I could see the bones under his skin.”

The voice Dergoul hears through the wall is surprisingly deep for a slender man. He likes this voice, the way it sounds when Utaybi recites poems for his cell neighbors.

“They were classic Arabic poems that related to our situation,” Dergoul says. “They had a poetry similar to that of Macbeth.” He is sitting on a staircase in London’s Central Mosque as he remembers this. It is not a good place to talk privately, but he does not want to be alone with a stranger questioning him. It would remind him of the interrogations in Guantánamo.

Utaybi is not a leader, but the other prisoners look up to him. “Everyone loved him,” Dergoul says, “his poems, his jokes, his personality. I don’t remember any other prisoner who was as outgoing as him. Mani was like a comedian, but he also had a serious side.” It is his serious side that gets Utaybi into trouble. “He didn’t put up with anything from the guards,” Dergoul says. “When they threw his Qur’an in the toilet, when they stepped on it or tore it apart, Mani pushed back. He always stood up for his rights.”

Utaybi’s first resistance is silence. He doesn’t speak to the guards or during his interrogations. Soon his silence spreads. The prisoners recognize the force of shutting down, and the entire cellblock falls silent. The guards’ power lies in their authority to interpret the prisoners’ behavior. They consider their retreat an attack and strike back. “They came in the middle of the night,” Dergoul remembers. “They didn’t let us sleep. They banged against the metal, they screamed, they dragged us out of our cells and inspected them. For nothing.” He pauses and looks at his hands. “They terrorized us.”

Small things gain great meaning inside the camp; there is power in controlling them. When Utaybi and Dergoul do anything that displeases the guards, they are punished by having small things taken away from them. Sometimes the power struggles start with an apple. “When we kept an apple instead of eating it right away,” Dergoul says, “they took away something we needed—our blankets, our soap, our toilet paper.” In the language of the Pentagon, these things are privileges, reflections of a higher standard. It calls them “comfort items.”

The temperature inside the cells is in the hands of the guards. They let the prisoners sweat. They let them freeze.

The removal of small things is the first level of punishment. It is followed by the removal of the company of others—banishment to a place called India. Block India has twenty-four cells and is only a few steps away from the other blocks of Camp 1, but it’s a distant place. It’s a block of loneliness. “They take everything away from you there,” Dergoul says. The prisoner is left with himself and the air conditioner blasting down on him from the ceiling. The temperature inside the cells is in the hands of the guards. They let the prisoners sweat. They let them freeze.

Utaybi and Dergoul are repeatedly sent into isolation. They can’t see each other, but they can hear each other and talk. Though isolated, they are not alone. Block India is designed to break the prisoners, but it hardens Utaybi. With each descent into isolation, his resistance grows stronger. The block where he is supposed to feel lonely unifies those who are there. They become a community.

Yasser bin Talal al-Zahrani is seventeen when he arrives in Guantánamo. There is a photograph of him in captivity, a portrait that looks as if it was taken for a gallery. Zahrani stares at the camera with questioning eyes. He has a slim face, framed by a wispy beard. He seems to be leaning forward, holding his head straight, but his shoulders are uneven, perhaps because his hands are shackled behind his back. It is a strangely colorful photograph, as if some of the colors were added after it was taken—the orange of his shirt, his slightly dark skin, his white skullcap, the sky-blue background.

Zahrani is confused. He does not understand why he is in Guantánamo. He does not understand what is happening to him, and he starts looking for answers. He hunches over the Qur’an and studies it until he has memorized all of its surahs. His faith is the one thing he can hold on to. He leads his cellblock in prayer and at night sings nasheeds, Arabic songs of struggle. He tries to give the other prisoners hope. He tells them that their suffering is God’s will and that He will end it soon.

On the wall of his cell, above the arrow pointing toward Mecca, hangs the book that rules Zahrani’s life. His Qur’an is wrapped in a white facial mask, its strings tied to the wire-mesh wall. It looks clinical, sterile, as if the book carries the risk of infection. It is supposed to protect the Qur’an, to keep it suspended in the cell, unsoiled, untouched by the wrong hands. Before each prayer, Zahrani takes the Qur’an out of the mask and looks at these white strings, how they are tied to the wall. Maybe at some point he sees the wall as a possibility, as a place to hang something.

The Qur’an is the most vulnerable part of the prisoners’ lives, and the guards know it. One day, after Zahrani returns to his cell from an interrogation, he notices that his Qur’an has been searched. To him, it is a desecration. He turns the Qur’an over to the camp’s imam, and when the guards return it to him, he refuses to take it back. He knows what will happen next. There is a word for it in the language of Guantánamo: he will be “ERFed.”

The Extreme Reaction Force, or ERF, is a rapid response unit on call in a building next to the cellblocks. When the guards feel threatened or believe that it is time to punish a prisoner, they call in the ERF. Dergoul has experienced the commandos’ brutal choreography. “The guards call the five cowards—five so-called men—who storm into the cell,” he says. “They all wear riot gear. The first one to go in has a large shield, and there is a sixth one who has a camera and films everything. They pepper-spray you in the face, they twist your arms and legs and shackle your hands and feet. And then they shave all your hair off, your beard, your eyebrows. They jump on your back. They take your head and bang it against the floor. They stick their fingers into your eyes.”

They retreat into their bodies, to the one place where they believe they still hold power, and they start shutting down their systems. They stop talking. They stop listening. And then they stop eating.

Dergoul closes his eyes and falls silent. “The pain is incredible, I can’t describe it,” he says as he opens his eyes. “When you see the ERF do these things to a prisoner, you think he’s going to die.”

Zahrani survives the day that the ERF returns his Qur’an. But he and Utaybi and Salami are beginning to ask themselves at what price they are surviving Guantánamo. They go back and forth between their cells and the interrogation rooms, between the ERF and solitary confinement, between despair and resistance. They retreat into their bodies, to the one place where they believe they still hold power, and they start shutting down their systems. They stop talking. They stop listening. And then they stop eating.

The internal battle over Guantánamo intensifies at the same time as the external one, which is about more than the prison, about more than justice. It is a battle over America.

In August of 2005, the lawyer George Daly is sitting in the comfort of his living room on Altondale Avenue, in Charlotte, North Carolina, reading a law journal. A story about the struggle of attorneys to defend their clients in Guantánamo catches his attention. Daly started out as a Republican and a corporate lawyer, but very quickly became a Democrat and began to defend Americans’ civil rights against their government. It began with the Vietnam War, when he defended conscientious objectors refusing to serve. Daly is sixty-eight and has been retired for six years when he reads about the defense attorneys’ fight. The story touches something in him. It reinforces his view of Guantánamo as a symbol of a separate, un-American America. He decides that he wants to defend one of the prisoners and starts looking for a partner.

Jeffrey Davis is, in many ways, the opposite of Daly. He is a staunch Republican and works at one of the biggest law firms in Charlotte, representing big companies and big money. During the Vietnam War, while Daly was defending those refusing to serve, Davis was in Đông Hà fighting against the Vietcong in the Tet Offensive. Thirty-eight years later, the Democrat Daly asks the Republican Davis if he wants to join him in his fight against his own government, and Davis immediately says yes.

Daly and Davis see the Constitution as the foundation of America, a scripture that answers the great questions, unfailing, untouchable. They believe in the Constitution the way the Guantánamo prisoners believe in the Qur’an.

The external battle over Guantánamo is a fight of faith, a fight revolving around one question: What kind of America do we believe in? “My entire life I believed that we’re the good guys, that we’re the world’s leader when it comes to human rights,” Daly says. “But that’s no longer who we are, and it saddens me. It scares me. We’re like the Russians in the 1950s and 1960s, like Chile in the 1970s, like Argentina in the 1980s. People are picked up in the middle of the night because somebody said something about them or because they were in the wrong place at the wrong time. And then they disappear.”

Only when Daly and Davis inform the court that their client’s name might also be spelled “Mani Shaman al-Habardi” does the Justice Department acknowledge that there is a detainee by that name in Guantánamo. Three months have gone by.

Mani Shaman Turki al-Habardi al-Utaybi’s fight for justice begins on March 17, 2005, the day that another prisoner tells his attorney that Utaybi is looking for a defense lawyer. The attorney contacts the Center for Constitutional Rights, a non-profit organization in New York that represents some of the prisoners and coordinates the legal fight against Guantánamo. The Center pairs Utaybi with Daly and Davis.

The attorneys file a habeas corpus petition, notifying the United States District Court in Washington, D.C., that they are representing their client in the matter of “Mazin Salih al-Harbi v. George Bush et al.” The Justice Department responds that there is no detainee by that name in Guantánamo. It is true—if one thinks in Roman letters. There are many different ways to spell Arabic names with the Latin alphabet. Only when Daly and Davis inform the court that their client’s name might also be spelled “Mani Shaman al-Habardi” does the Justice Department acknowledge that there is a detainee by that name in Guantánamo. Three months have gone by.

It is the beginning of a struggle that the Justice Department shifts to the realm of formalities. It is never about the prisoner, about who he is and what he has done. It is about the spelling of his name, about the question of whether his lawyers are allowed to send him mail, whether they are allowed to visit him and when and for how long. It starts with the Justice Department raising the question of whether Daly and Davis are really Utaybi’s lawyers—where is their power of attorney? They have, after all, never seen Utaybi. And they are not allowed to see him if they are not his attorneys.

A government that does not answer questions begins to question everything. It does not want to prove anything, but accepts only what has already been proven. Utaybi is faceless in Civil Action No. 05-CV-1857 (CKK); he has only the voice of two lawyers, speaking on his behalf without ever having spoken to him. Sometimes Daly feels like he is caught in a surreal procedure. “There’s a book that basically tells this whole story,” he says. “It was written by Kafka and is called The Trial.”

At the same time, David Engelhardt, an attorney in Washington, is struggling to defend Salami. He petitions the court to order that “George W. Bush, 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, DC 20500” either free “Saleh Ali Abdullah Al Salami, Guantánamo Bay, Cuba,” or disclose the reasons for the prisoner’s detention. A week later, on December 30, 2005, a lawyer at the Justice Department sends an email to the court saying that she could not confirm the identity of a detainee by that name. She signs off wishing a “Happy New Year.”

The government slows down the court proceedings as much as it can. It uses the same tactic it applies in Utaybi’s case. But this time, only one letter in Salami’s name is misspelled and only his fourth first name is missing in the complaint. The prisoner the Justice Department claims not to have found under the name “Saleh Ali Abdullah Al Salami” is later discovered under the name “Salah Ali Abdullah Ahmed Al Salami.” It takes two months.

Utaybi and Salami do not know that there are lawyers in Charlotte, Washington, and New York demanding that the President of the United States justify their incarceration. It is impossible for them to know. In Guantánamo nobody tells them, and the lawyers cannot get to them. Zahrani has no defense attorney. Maybe he did not want one. Many of the prisoners do not trust lawyers. They have been visited by men who claimed to be their attorneys and turned out to be interrogators.

The lawyers are losing time, and Engelhardt, Daly, and Davis will later ask themselves if they lost their clients during those months. It is a crucial period. While the Justice Department claims it cannot find their clients in Guantánamo, Zahrani, Utaybi, and Salami are starving themselves in their cells.

Colonel Michael Bumgarner has been leading the Joint Detention Group at Camp Delta since April 2005. He came on a mission to give the prison a more humane face. Bumgarner keeps a printout of the Geneva Conventions on his desk, and when, two months after his arrival, several dozen prisoners go on a hunger strike, he takes an unusual path. He goes to visit the prisoners.

Bumgarner visits a man who is said to have influence over the prisoners. Shaker Aamer is thirty-eight and, like Zahrani and Utaybi, was born in Saudi Arabia. He is accused of having been a high-level Al Qaeda operative in London before he went to Afghanistan in the summer of 2001. Aamer has a thick beard and long black hair tied in a ponytail. He wears glasses and speaks refined English. The guards call him “The Professor.”

For more than four hours, the colonel and the professor sit on opposite sides of a table. They talk about living conditions and the prisoners’ hunger strike, and Bumgarner hears something he finds hard to believe. Aamer tells him about a vision, a prophetic dream that several prisoners had. They saw their redemption. They dreamt that three of them had to die in order to liberate the others.

Islamic law forbids suicide, but the Sharia is not untouchable. They would be permitted to take their own lives, Lahmar says, if their deaths protected state secrets or served the common good.

Islamic law forbids suicide, but the Sharia is not untouchable. Saber Lahmar, an Algerian prisoner who is respected by the others as a religious authority, tells them about a fatwa, a legal opinion by a mufti that allows for an exception. They would be permitted to take their own lives, Lahmar says, if their deaths protected state secrets or served the common good.

Bumgarner is alarmed. In order to defuse the conflict, he gives in to some of the prisoners’ demands. He orders that “The Star-Spangled Banner” no longer be played at the same time that the call to prayer echoes through the camp. During prayer times, he has yellow cones marked with a large “P” placed in the corridors between the cellblocks so the prisoners aren’t disturbed. He raises the daily amount of calories in the prisoners’ food from 2,800 to 4,200.

The concessions are minor; they do not affect the prison’s balance of power. But Bumgarner makes another seemingly small concession, and he will realize the consequences of it only months later. He changes a rule in the cellblocks for “compliant” prisoners. One of these blocks is Camp 1, where Zahrani, Utaybi, and Salami are kept. Bumgarner orders that the lights in the cells be turned off from ten at night until four in the morning. The prisoners should be able to sleep. They are not to be disturbed during the night.

Aamer ends his hunger strike, and Bumgarner takes him to Camp 5, the high-security zone. Aamer manages to convince other prisoners, who are respected as figures of authority, to end their hunger strikes. In some cellblocks, prisoners start applauding upon seeing Aamer. Some of them cry. It is the beginning of what Bumgarner will later call the “time of peace.”

Bumgarner sits down at a table with Aamer and five other leaders of the prisoners. He has their handcuffs removed. They present Bumgarner with their demands, and he promises to treat the prisoners “in the spirit of the Geneva Convention.” A few days later, the six prisoners, who call themselves “The Council,” are allowed to meet without Bumgarner being present. When they exchange notes and the guards interfere, some of them swallow the notes. The “time of peace” is over.

The time of hunger returns. Soon, more than 130 prisoners are starving themselves in their cells—more than ever before. They refuse to touch their food until they are either charged or released. Bumgarner isolates the hunger strikers at the prison’s periphery, in various blocks. Romeo. Lima. Tango. Echo. Camp Echo is the most remote of those blocks, a place that, under different circumstances, is the prisoners’ only connection to the outside world. It is where they meet with their lawyers. Now it becomes the place where Zahrani, Utaybi, and Salami completely retreat.

Aamer is starving himself in Camp Echo at the same time they are. With a stenographer’s meticulousness, he records in his journal how the guards try to break their resistance. How they take away their clothes, except for a T-shirt and pair of shorts—because they know that a Muslim man must cover his body from navel to knees. How they blast songs by The Eagles in their cells, unbearably loud. How they turn off the water before prayer time, so that the prisoners are forced to wash themselves in the toilet. “Sometimes,” Aamer writes, “I stop asking myself if they are human beings.”

Bumgarner faces a resistance never seen before at Guantánamo, an unparalleled determination among the prisoners. A hunger strike, as defined by the Pentagon, begins when a prisoner has refused nine meals in a row. By that definition, approximately one in every four prisoners is now on hunger strike. The commander and his guards can no longer reach them, and they solve the problem mechanically. They access their bodies.

The prisoners call the hunger strikers the “force-feeding club.” In the language of the Pentagon, the term “force-feeding” does not exist. It calls the procedures in the clinic “re-feeding.”

Zahrani, Utaybi, and Salami are taken to the camp’s clinic and instructed to throw their heads back. Then the doctors insert a yellow tube into each man’s nose and push it through the esophagus and into the stomach. The force-feeding begins. The tubes, made by Viasys Medsystems, model number 20-5431, are three feet and six inches long and thin like electric cables. Two to four times a day, the doctors pump a nutritional fluid through the tubes. The prisoners call the hunger strikers the “force-feeding club.” In the language of the Pentagon, the term “force-feeding” does not exist. It calls the procedures in the clinic “re-feeding.”

While at the clinic a mixture of dextrose, potassium chlorate, magnesium sulfate, and iron drips into the hunger strikers’ stomachs, the compliant prisoners have a new taste in their mouths. Their meal plan has been expanded to include PowerBars and Gatorade. For them, Wednesdays now end with “pizza night.” They ask for Pepsi to wash it down, because they reject Coca-Cola as too American.

Some of the hunger strikers rapidly lose weight. They are malnourished despite the force-feeding, because soon after the sessions they stick fingers down their throats and throw up. Some of them manage to reverse the process of force-feeding; they suck their stomachs empty with the same tubes that fill them. The Pentagon flies in “restraint chairs”—wheelchairs in which a prisoner’s head, arms, and legs can be fixed. The hunger strikers are strapped to these chairs until they have digested the nutritional fluid. The American company that produces the chairs markets them with the slogan, “It’s like a padded cell on wheels.”

In the spring of 2006, few prisoners aside from Zahrani, Utaybi, Salami, and Aamer are still on hunger strike. Some of them have become so weak that they need walkers. The walkways between the blocks in Camp Echo are reinforced with concrete so that the guards can move the prisoners around the camp in wheelchairs. “There’s no hope left in their eyes,” one officer tells Aamer. “They are ghosts, and they want to die.”

At the end of April, the Justice Department tells Daly and Davis that Utaybi has been cleared to be transferred to Saudi Arabia. In mid-May, eight months after he began to represent Utaybi, Daly is allowed to board a propeller plane in Fort Lauderdale and fly to Guantánamo to meet with his client. The Justice Department prohibits Daly from telling Utaybi that he has been recommended for transfer to Saudi Arabia. But Daly is allowed to ask him if he wants to go back to Saudi Arabia, and he hopes that Utaybi gets the message.

In Washington, David Engelhardt receives a DVD in the mail. Salami’s father in Yemen has recorded a video in which he pleads with his son to trust his American lawyers. Engelhardt is now ready to meet with Salami. All he needs is the Justice Department’s permission.

When Daly and his interpreter land in Guantánamo, an officer tells him that Utaybi does not want to see him. Daly is stunned, and the interpreter suggests that they send Utaybi a message. “Please meet with us,” he writes on a piece of paper. For two days, Daly waits to meet with his client. But Utaybi does not appear. Maybe he does not want a lawyer. Maybe he does not know that he has a lawyer. Maybe the guards only told him that he had an “appointment.” But that is also what they say before an interrogation.

Daly leaves Guantánamo without seeing Utaybi. The day after his departure, guards in Camp 1 find a prisoner unconscious in his cell, foaming at the mouth. They shout “snowball” over their radios—code for a suicide attempt. Doctors later determine that five prisoners had swallowed sleeping pills and antipsychotics secretly stashed in their cells. All five survive.

That same afternoon, when the guards start searching other prisoners’ cells for hidden pills—a search that includes their Qur’ans—an uprising breaks out in Camp 4, the block where prisoners are dressed in white and considered cooperative. One prisoner pretends that he is about to hang himself and lures the guards to a part of the camp where they come under attack. The guards shoot rubber bullets at the prisoners and put an end to the uprising. They think it is over.

On June 9, shortly before midnight, according to the Pentagon, Zahrani, Utaybi, and Salami retreat to the back of their cells. They tie torn bed sheets and clothing into nooses. The lights are off in their cells, but they have to hurry. They know that the guards are supposed to patrol their block every three minutes. They place clothing under their blankets and make it look like sleeping bodies. They hang sheets in front of their sinks to obscure what is happening behind them. They tie the nooses to the wire-mesh walls and stuff their mouths with bales of cloth—maybe to muffle their screams, maybe to suffocate themselves. They step on the sinks and put the nooses around their necks.

And then they jump.

Shortly after midnight, the guards discover their dead bodies. They are hanging from the walls.

Guantánamo becomes a different place that night, a battlefield. Rear Admiral Harry B. Harris, the camp’s commander, holds a press conference and calls the suicides “an act of asymmetric warfare.” A spokeswoman for the State Department calls them “a good PR move.” In Guantánamo, Colonel Bumgarner holds up a piece of pork and says, “To our three dead brothers.” Then he bites into it.

The Pentagon considers burying the dead in Guantánamo. Then it releases them. The bodies of prisoners 093, 588, and 693 are dissected, then flown to their home countries in zinc coffins. The autopsy reports are never published.

In a morgue in Riyadh, Talal Abdallah al-Zahrani lifts a white sheet and sees a face that looks like his own. The father raises his cell phone and takes the last photograph of his son.

This piece originally ran in Der Spiegel on August 13, 2007, and has been translated from the German and updated by the author.