I

t would be absurd to think a small library of books could incite young men to homicide, persuade them to accept the idea of suicide, or even precipitate a catastrophic European war. Nevertheless a small library that made the rounds of the Young Bosnians as they prepared for the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary in June 1914 suggested at the time, and later, that their reading influenced the course of events in that fateful year. The selection was small: the titles in question could have been loaded into a backpack and read on a summer hike by any or several of the plotters. They had an appetite for books and uncompromising attitudes towards them; over a game of billiards, the mladobosanci—some of them pan-Slavs, some ultra-Serbian—would talk incessantly about what they had read and, if they disagreed, the argument was usually settled with the rough and ready use of billiard cues.

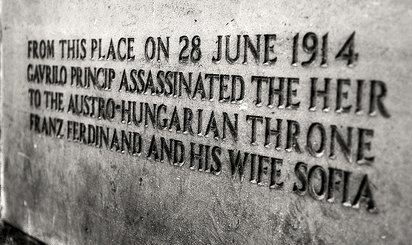

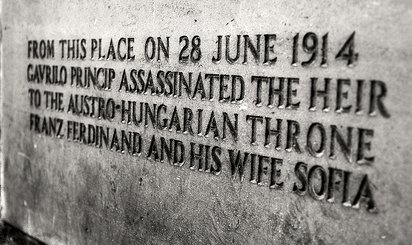

Gavrilo Princip was the young man who pulled out a pistol—after a grenade had failed to reach its target—and shot the Archduke and his wife Sophie at the northern end of the Latin Bridge in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914. Princip’s direct accomplices that day are less well known: Nedeljko Čabrinović, a typesetter; Danilo Ilić, a teacher turned journalist; Trifko Grabež, expelled from school into the wilds of Serbian nationalism; Muhamed Mehmedbašić, a conspirator from the Bosnian Muslim nobility; Cvjetko Popović and Vaso Čubrilović, both students. The Mlada Bosna group was closely associated with the clandestine “Black Hand” movement, dedicated to the cause of “Greater Serbia.” Several of the plotters were members of both. When the Serbian authorities arrested the conspirators, Austria-Hungary issued the July ultimatum, and the rest is well known.

They moved from one jacket pocket to another; long passages were committed to memory. Some had a talismanic quality for these readers, as The Catcher in the Rye had for Mark Chapman, the murderer of John Lennon.

Before we come to the catalogue itself, a few words about some of the plotters’ literary habits. Nedeljko Čabrinović, the typesetter, was a pedagogue: he had a shortlist of recommended texts for his colleagues and workmates, whom he considered to be his apprentice typographers. These were to be “read so as to know how to distinguish the truth from the lies that the priests tell” (at least two of the Young Bosnians were the children of Orthodox priests). His list contains 26 books in all, and I have included several of them in the catalogue that follows. The journalist, Danilo Ilić, was translating until the day of the assassination. On the evening before, he was finishing a translation of Oscar Wilde. Among his translations are works by Kierkegaard, Strindberg, Ibsen, and Poe.

Every “mladobosanac” wanted to be a poet. Nearing his death in detention, Princip confessed to his prison doctor, Morris Pappenheim, that he was ‘always lonely, except in libraries…books mean life to me. So it’s extremely difficult for me now, without reading.’ Princip had acquired “the ideals of life” in 1911, he told Dr. Pappenheim, and decided to join the mladobosanci. It was also the year he fell in love. His last verses were written on the walls of his cell, a few days before his death, summoning forth the shadows that terrify the ruling classes as they sit quaking in their castles. Under Habsburg law at the time of his conviction he’d been too young—by 27 days—to be sentenced to death. He received the maximum 20-year prison sentence. He was held under harsh conditions at Terezín prison for three years and ten months; he died of skeletal tuberculosis, which had been eating away at his bones and led to the amputation of his right arm.

Princip gave no evidence of talent when he was at liberty to write. He showed Dragutin Mras, another member of the group and a poet, a poem about roses that bloom for the beloved at the bottom of the sea, but Mras did not care for the poem. Apparently he talked about his poems to the Bosnian Croat writer Ivo Andrić—who was a little older than Princip and many years later a Nobel Literature laureate—and even promised to produce them. When Andrić pressed him, Princip told him they had been destroyed. His only lyrical text to have survived dates from 1911, preserved in the visitor’s book at the traveller’s lodge on Mt. Bjelašnica.

The list I’ve assembled here as a Great War catalogue is gleaned from scattered references in Sarajevo 1914 by Vladimir Dedijer, a Tito stalwart (and official biographer) who later fell from grace. The editions were borrowed from various libraries or discovered in bookshops, exchanged among the assassins, bought and sold several times, and in some cases burned. They were read in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, and France by young men in student hostels, cheap hotels, bars, and restaurants; they accompanied them to the ice cream parlours of Baščaršijske in the old city of Sarajevo. They moved from one jacket pocket to another; long passages were committed to memory. Some had a talismanic quality for these readers, as The Catcher in the Rye had for Mark Chapman, the murderer of John Lennon.

What Is to Be Done? by Nikolay Chernyshevsky.

What Is to Be Done? was written in 1862 while Chernyshevsky was in prison awaiting trial on charges of revolutionary activity.

Nedeljko Čabrinović was 14 when he read this book. His father Vaso found him reading it, gave him a hefty slap, and pulled the light bulb out of the lamp. Vaso weighed 120 pounds and had the big fists and martial temperament of a hardened drinker. Čabrinović was the eldest of nine children. Vaso beat them for the slightest infraction of the rules—any rules, whether they were laid down by the family or imposed by society. Once, working as an apprentice, Čabrinović hit a fellow worker at the printing workshop. Vaso did not come to his son’s defence; instead he threw him out of the house. Čabrinović promptly left for Zagreb, where he wandered about for a month. When he returned home, dirty and hungry, his father called the police. The boy spent three days in jail.

Čabrinović had become his own man, the master of his own life, and of his own death too, which is often the way.

Mont Oriol by Guy de Maupassant.

A meeting between a young, enthusiastic militant and a nationalist dignitary could be fraught with difficulty. When Major Vasić, a close ally of the Black Hand member Vojislav Tankosić, met Čabrinović in a Belgrade park and saw this book in his pocket, he was terribly disappointed. “Who is this Maupassant? What is love? Where will it lead? Young men who read this kind of literature will go blind.” This is how he must have spoken. He then donated his collection of Serbian folk songs, in the hardcover edition, to the mladobosanci. It was a book designed to be kept over a man’s heart, in the pocket of his military jacket, where a bullet could be stopped and his life saved.

Trifko Grabež and Gavrilo Princip did not allow Čabrinović to visit the Cetnik duke and Black Hand notable Vojislav Tankosić, because Čabrinović always had a grin spread across his face (he used to say that he couldn’t help it, his expression was “just like that”) and the overbearing Tankosić had no time for frivolous people. He imagined something must be hidden behind a smile and felt comfortable only in the company of eager fanatics. He gave the mladobosanci guns, bombs, and spending money for the journey to Sarajevo.

Education of the Will by Jules Payot.

Čabrinović read this pedagogic, self-help book in 1912, in Trebinje, during another spell in prison: he was suspected of having organized a strike of print workers, destroying machinery, and attacking strikebreakers. The volume may well have been part of the prison library: libraries for inmates were a feature of the correctional reforms introduced in Bosnia and Herzegovina by the Austrians. In the same year, perhaps because he had steeled his will, perhaps because he was physically stronger, Čabrinović was no longer beaten by his father. In a letter to a friend, Vaso complained: “Who is this man I have fathered, and raised, on whom I spent our money and patience? He is a dreadful demon, seizing every opportunity to go against his own father and never showing him the obedience he is due.” Čabrinović had become his own man, the master of his own life, and of his own death too, which is often the way. At the trial, he made the following statement: “I have no wish to accuse my father, but if he had practiced a better pedagogy, I would not be sitting in this dock.”

News from Nowhere by William Morris.

A copy of a translation, which passed between Princip and Čabrinović, is still intact and bears their signatures. They read News from Nowhere in 1912, and marked the passages that impressed them. Princip underlined the words, “since we want to avoid centralization.” Čabrinović put a mark beside the words, “about the lack of interest of workers in communist society.” At the end of the book, Čabrinović noted in neat handwriting: “I read this book at a time when both socially and as an individual, I found myself completely at odds with its optimism.”

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes by Arthur Conan Doyle.

Princip loved adventure novels: Dumas, Scott, and especially the adventures of Sherlock Holmes. He would have known this passage, in which Watson describes his puzzling friend:

Serbian Deception by Svetozar Marković.

The socialist and political activist Svetozar Marković wrote that ideas in small countries are only as valuable as the people who represent them. The mladobosanci subscribed to Marković’s view that societies can learn from the actions of morally strong and socially conscious individuals, whose example will then contribute to the creation of a new and better kind of person. Vladimir Gaćinović met Trotsky by chance at a café in Paris, where the socialist revolutionary was impressed by the young man’s revolutionary zeal. Gaćinović reassured Trotsky that all the mladobosanci were striving for the morality of a simple life and that they all lived by the ascetic standards of the struggle. He told Trotsky that they abjured alcohol and saw all declarations of love as an affront to their virginal dignity. Trotsky seems to have been reassured on the question of sexual abstinence and, in Princip’s case, it was the truth. In jail he confided to Dr. Pappenheim that he had never had sexual relations. At the time, he was clothed in a rough prison shirt without buttons, which he attempted to gather over his chest with his one good hand.

He sent a suitcase from Belgrade with anarchist literature to his sisters in Sarajevo. The books frightened his mother. In the dead of night, while the neighborhood slept, she burned them one by one.

The Happy Prince by Oscar Wilde.

Princip once discovered Čabrinović’s sister, Vukosava, reading a frivolous novel about the secrets of a Constantinople palace. He criticized her taste in literature and brought her Wilde’s story as a better option. Years later, Vukosava described Princip as a reclusive boy, sometimes humorous, even sarcastic, with deep eyes, beautiful teeth, and a very high forehead. The Sarajevo judge, Leo Pepper, saw him immediately after his arrest and described him as follows: “The young man was stunted, puny, elongated, and with a pasty face, making it difficult to imagine how such a small, quiet and unassuming person could decide to commit an assassination.”

The Newcomers by Milutin Uskokovic.

On the same occasion, Princip lent Vukosava a copy of this novel by Milutin Uskokovic. Čabrinović may have had even more of an influence on his sisters than Princip. In Karlovac, where Vukosava attended a teacher training college, she proclaimed herself an anarchist, while her little sister Jovanka was a “convinced socialist’. On July 14, 1912, Čabrinović wrote to Jovanka: “You ask if I am still a socialist. I am. Just a little smarter and a little different. You ask me if I am hungry? So far, I am not. But I have been quite a few times. Last feast day, you ate roast pork and I dry bread.” He sent a suitcase from Belgrade with anarchist literature to his sisters in Sarajevo. The books frightened his mother. In the dead of night, while the neighborhood slept, she burned them one by one in the kitchen stove and broke up their ashes with a poker. On October 15, 1915, Milutin Uskoković jumped into the Toplica River and drowned. His friends claimed that the “collapse of the fatherland” was the cause of his actions.

The Critic as Artist by Oscar Wilde.

Danilo Ilić was translating this book in 1913. At the time he was preoccupied with preparations for the assassination. Towards the end of the book, he seems to have given up. Until the last day, he tried to persuade Princip and Grabež that they should abandon the assassination plan.

(The Ballad of Reading Gaol)

William Tell by Friedrich Schiller.

In Schiller, as in the old Swiss legend, William Tell kills Gessler, the Habsburg governor, and prompts a rebellion by the Swiss against the harsh hand of Austria. The Bosnian freedom fighter, Bogdan Žerajić—a national hero and a role model in the eyes of the Young Bosnians—was obsessed by the play while he was preparing his assassination plan. The year was 1910 and his target was General Marijana Varešanin, the Provincial Governor of Bosnia-Herzegovina. After firing five bullets at Varesanin and failing to kill him, Zerajic took his own life. In his pocket, the police found a notebook full of quotations from Schiller’s play. In prison, Princip claimed that as early as 1912, at the tomb of Žerajić, he had vowed to avenge him. The night before his attempt on the Archduke’s life, he stole flowers from other graves and laid them on his hero’s.

The History of the French Revolution by Peter Kropotkin.

In addition to notebooks, the Sarajevo police found a badge on Žerajić’s person, which the inspector described in his official report as ‘consisting of a red cardboard circle about 10 cm wide, decorated with a red border, which shows a portrait of a man with long hair but without a beard, whose face is distorted with passion, with open mouth and tousled hair.’ The evidence was sent for further investigation to headquarters in Budapest, where the motif was recognized. The report reads: ‘It is identical with the cover of the book The History of the French Revolution, written by Peter Kropotkin and published by Theodore Thomas of Leipzig.’ The authorities buried Bogdan Žerajić’s body in the part of Sarajevo cemetery reserved for suicides and vagabonds, while his head was presented to the Criminal Museum. At that time, Cesare Lombroso’s theory that every criminal had recognizable defects, including cranial asymmetry, was popular among criminologists, so the police believed that Žerajić’s head could be of use to science. After the fall of the Habsburg monarchy, the head was reattached to the body.

Underground Russia by Sergei Stepnyak.

Readers of these ‘revolutionary profiles and sketches from life’ by the Russian revolutionary nihilist note the warmth and care with which Stepnyak talks about his friends and comrades. Until the last moment, Grabež and Princip thought Čabrinović would not be able to take part in the assassination. Grabež thought him gullible and untrustworthy, prone to ‘see a friend in every man’. Later, Princip was to describe his colleague to Dr. Pappenheim as a ‘bad wordsmith’ with no great intelligence. Danilo Ilić once said that Čabrinović, the one who threw the grenade at the Archduke’s car—it detonated under another car in the procession—had done so chiefly to regain the trust of friends. The night before the assassination, Čabrinović read Underground Russia for the umpteenth time. In the morning, he packed the book into a pocket, along with the explosives, and went to the appointed place beside the river.

Princip said that he regretted that the children had lost their father and mother, that he was sorry he had killed the Duchess, but that he had no regrets about killing the heir to the throne.

When Countrymen Meet and Other Stories by Jasija Torunda.

On the margins of this book Princip wrote: “What your enemy does not need to know, do not tell to his friend. If I overhear a secret, then it becomes my slave. If I reveal the secret, then I’m its slave.” At the trial, during his final testimony, Čabrinović asked to consult with Princip. When they stood in front of the judge, Princip calmly replied that he spoke according to his conscience. In his closing argument, Čabrinović said that he was sorry that he had been been greatly impressed by the Archduke’s last words: ‘Sofia, stay—live for our children.’

Princip said that he regretted that the children had lost their father and mother, that he was sorry he had killed the Duchess, but that he had no regrets about killing the heir to the throne. At that point, Čabrinović quickly got up from the bench and said that even he did not regret killing Franz Ferdinand.

The Seven who were Hanged by Leonid Andreyev.

Andreyev wrote about the execution of two criminals and five political prisoners: describing how they went willingly to their deaths, what they endured, and their feelings on the eve of their execution. Before his own execution, Danilo Ilić wrote three letters to this mother. In two of them, he asks her for new clothes, but we’ll never learn what was written in the third. Detectives apparently found it at his mother’s house and ripped it up. He was hanged, together with Miško Jovanović and Veljko Čubrilović, on February 3, 1915. The hangman, Alois Zajfrid, later told reporters that the condemned men were unusually calm on the scaffold. He could not remember which of the three had said: “Please just don’t torture me for a long time,” to which the hangman answered, “Don’t worry, I know my job well, it’ll all be over in a second.”

Poems by Milan Rakić.

In hard but all too familiar times, Princip would have to sell books in order to buy food. However, he never sold his Rakić. His best-loved poem was “At Gazimestan” and the key verse:

In Terezin, with the tuberculosis in its last stages, Princip had a gangrenous wound to the chest, and his right wrist was so rotten that his lower and upper arm had to be tied with a silver wire. He died at 18:30 on April 28, 1918.

The Mountain Wreath by Petar Petrović Njegoš.

An epic poem about the struggle of the Montenegrin people for justice and dignity under the Ottoman rule by the prince-bishop, Petar Petrović Njegoš, is the most important in the library and ruled them all. Princip knew it by heart. He grew up in a house built below a black creek, which from 1875 was the site of a camp of rebel Serbian rebels fighting for freedom from Ottoman serfdom. The Turks conquered it two years after his birth and killed 150 insurgents there. When Princip first went to Sarajevo at the age of 13, he ran out of a café shouting ‘Turks! Turks!’ The clothes of the Bosnian Muslim customers had terrified him. By the time he conquered that fear, he had memorized the whole of ‘Mountain Wreath’.

A brief postscript. We have proof that the Young Bosnians did a lot of reading, and the question remains: where are the other, non-incriminating books, omitted from the charge sheets drawn up during the investigation? Books that failed to confirm the motives of the Sarajevo assassins: the romances and adventure novels that Princip loved, the bedtime reading, the books that wiled away the boredom of a rainy day, and the poetry—above all the love poetry. They are probably lost forever in the multilateral tussle between the Serbian army, the Serbian government, the Black Hand movement, the Austrian investigators, and the admiring romantics and historians of all persuasions. How many were there and how would they have changed our sense of the Great War library if they’d come to our attention? Where are Princip’s lyric poems? Where are those roses at the bottom of the sea that he promised to the Nobel Laureate, Ivo Andrić?