My friend Majed writes me one of his periodic emails, in Persian:

Dear Salar:

Today, after several days in the mountains, I got back to the city. Thank god I’m alive. I’d gone with the police to see a firefight against some Taliban and drug smugglers. Afterwards, we ate dinner at the foothills and the commander said that now that the moon was out we ought to get going. We’d gone about a hundred paces when the area we’d been eating at took a direct hit. There were about 40 of us. And had we lingered a little longer, surely we would have turned into a nice meat-salad. I’ll write again in a few days.

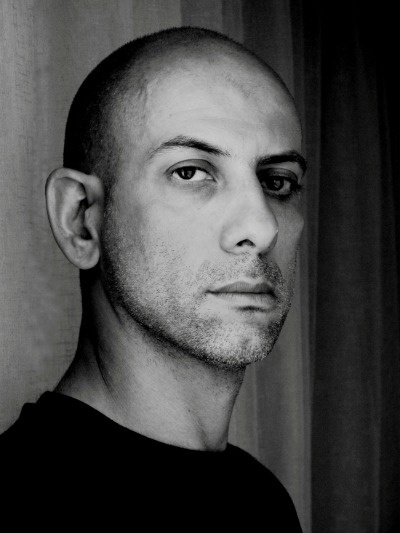

Majed is always getting himself killed. It is kind of what he does for a living. He is of a very small breed of “locals” in the Middle East who are “embedded” by default. They don’t have the full support—or any support for that matter—of the American or British military when they report from battle. Nor do they write blockbusters of their experiences for a mainly English reading audience. Nor do they arrive with escorts of ten armor-plated vehicles and thrice as many bodyguards to report for CNN while their camera people zoom in on the troubled location from the safe distance of two miles off. Majed, you could say, has something of a death-wish, which troubles me quite a bit. The first short documentary I saw of his was of an elderly couple in Southern Lebanon who had gone back to their orange grove after the 2006 Israeli war. The grove, pregnant with ripe oranges had also become a field of cluster bombs—in the soil, on the branches, even lodged inside the fruits. The couple would spend the first half of the day defusing the bombs and the second half of the day picking their crops off the trees to sell at the market. Watching the video (even though you know it is a finished piece and that Majed has come out of it in one piece), you cannot help but hold your breath each time the old farmer approaches one of those little devils to defuse it with his bare hands.

In general, I’m always holding my breath with this child of Khuzestan, an Arab speaking region of southwestern Iran that took the brunt of the devastation during the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s—a war that some estimates say took the lives of a million people and is considered the longest conventional war of the 20th century. Majed notes that during that war a currency among the local kids was shell fragments; they would collect them, exchange them, put value on the uniqueness of some of the shapes and forms.

Often I think that Majed is still continuing to collect fragments of that nature. And in his hunt, he sometimes ends in tight spots—like that time in Beirut where he had to make himself small behind a still tank’s caterpillars while bullets zinged off the metal. When he’s not home in Tehran, most likely watching Al-Jazeera in Arabic, he is traipsing around with his camera. I first met him just that way while he was shooting a segment of a documentary about the escalating drug epidemic in Iran. He had been staying inside a rehab center to the far south of Tehran for 48 sleepless hours, taking videos of boys who are collected off the drug parks and sent to such centers for pointless 3 week crash cleansings to rid them of whatever habit they have.

Majed pointed to those soldiers and said, “Do you know how strange it is to see those guys up close? They look like creatures from outer-space.”

It was about a month prior to Majed’s latest email that we both happened to be in Tehran again at the same time. The security police were out in force that particular day because it was the anniversary of something or other and the hapless opposition had directed people to come out into the public squares and demonstrate. No one had shown up, especially not in the public squares, except for the riot police, of course. So we had settled in front of Majed’s TV instead, watching the Arab Spring unfold on Al-Jazeera. Majed would periodically translate for me from Arabic to Persian. Then the news shifted elsewhere, showing American soldiers on patrol. Majed pointed to those soldiers and said, “Do you know how strange it is to see those guys up close? They look like creatures from outer-space.” I asked why, and he said, “Look at all that stuff they carry on them. I’ve seen them in Iraq, I’ve seen them in Afghanistan—even in the dead of summer when you want to rip your t-shirt off, they carry all that baggage. Your heart breaks for these kids. You want to go up to them and take all that weight off. The poor bastards. Why does their government do this to them?”

The Things They Carried. I translated the words to Persian and explained to Majed that it was the title of an American classic about American soldiers at war. I told him it was a story I loved but never used in the literature classes I sometimes taught at City College in New York. “How come?” he asked. “The piece is over-anthologized.” Then I sang, “Zapped while zipping.” “What?” Majed asked. “Zapped while zipping”—how does one translate that into Persian? I did my best, and of course Majed understood right away. “It happens in The Things They Carried. The soldier is taking a piss and he gets shot and dies. His platoon mates call it ‘zapped while zipping.’” We were both quiet for a while and the TV had gone onto something else. I think a commercial. I turned to Majed and he turned to me and I said, “Brother, wherever you are on the road, don’t get zapped while zipping, all right?”

“Inshallah!”

Majed’s email continues:

This is Afghanistan. Nine dead, twelve wounded. I heard the news from the television of a mobile shop while walking along Kabul’s plush, much preferred by westerners Shahr-e-Now (New Town) district. I’d come to buy a sim card for my phone. The news made me freeze in front of the store, yet other pedestrians continued on their way like nothing had happened. It actually seemed as if the only strange thing they saw was my reaction to the report. I was wearing Afghan dress and they found it odd that another Afghan should find such ordinary bit of news worthy of stopping for. The report said that it had been a suicide bomber—not more than a couple hundred meters from where I was standing now. The shopkeeper paid no attention to what was on TV, but eyed me with a look of utter astonishment on his face. So instead of stepping inside the store, I started to walk, though I could feel the eyes of the shopkeeper still on me. I could tell that from my reaction to the news he’d gathered I wasn’t Afghan and he was probably asking himself, “What other hell could this fellow be coming from?”

A little further up the road I entered another shop and bought my sim card. As the shopkeeper was filling in my identity form, he asked, “Why are you in Afghanistan?” I don’t know why I didn’t tell him that I was a documentary filmmaker. Instead I lied and said, “just traveling around.” He gave me a puzzled look, probably asking himself, “What kind of a madman is this?” On the way back I kept wondering why the other people on the street were so indifferent to the news about the bombing. In the taxi, the driver finally said to me, “Brother, this is our lot everyday. You can’t bother your brain with it too much. This is Afghanistan.”