By Rose Lichter-Marck

“Landscape photography can offer us, I think, three verities—geography, autobiography, and metaphor.”

– Robert Adams, “Truth in Landscape”

The Salton Sea, America’s third largest land-locked body of water, is a hundred-year-old mistake. Fifteen miles wide and thirty-five miles long, the saline lake was created when the swollen Colorado River breached the irrigation canals of California’s Sonoran desert in 1905. Instead of gushing south, toward the arid Imperial Valley where man was striving to turn the desert green, millions of gallons of fresh water rushed north toward the Salton Sink, an endorheic basin sitting 300 feet below sea level.

In the early years of the last century, as a fever for land reclamation and agricultural development gripped the American west, engineers crafted an ambitious plan to import water to the Imperial Valley from the Colorado River, hundreds of miles away. Almost immediately environmental and mechanical hiccups like blockages and overflows plagued the project, betraying its capricious nature. The malfunctions did nothing to deter the flocks of settlers who migrated there, enticed by subsidies and a chance to be a part of the agricultural gold rush. In California, the land offers opportunities that outweigh the risks.

It takes more than three hours to get from LA to the Salton Sea. K drives while I stare out the window at the twisting ribbons of highway, the brown shrubby mountains, the sentinel windmills that mark our arrival in the desert.

K and I had met ten months before on a college campus where neither of us were students in a state in which neither of us lived. Our first conversation was about basketball; then we commiserated on the shittiness of recent break-ups. Later we got drunk and rolled around on the floor of a dusty storage room. Then we went back to our respective cities of residence, and for three quarters of a year we touristed in each other’s lives. I ignored the signs that he was haunted by his last relationship and tried to forget the fact that we lived on opposite coasts; he bluffed his commitment to me when he wasn’t totally sure. He hurt me with his ambivalence but I kept taking his calls. Things got so confusing that when I arrived in LA for my family’s Passover Seder, I didn’t know if seeing him meant we would start over or finally say goodbye. I wasn’t sure which outcome I preferred.

We went out to dinner but did not discuss the future. Instead we talked about road trips. “Let’s go somewhere,” he said. It had been years since I’d been to the desert, and I’d always wanted to see the droughty Imperial Valley, the mysterious Salton Sea, the tenacious settlements that speckle its shores. I wondered about the almost 200,000 people that still live there, despite the now-gutted economy, the years of water shortage, and environmental conditions that are among the harshest on the planet. Why do humans hold on to things that are not meant to last?

I looked across the table at K. What was two more days in the car with his hand resting on my knee? “Okay,” I said. “Let’s just go.” Besides, it was Passover, as good a time as any to wander in the desert.

By the time we pull into a state park on the eastern shore of the Salton Sea, the sun has already set behind the jagged peaks of the Santa Rosa Mountains in the west, leaving the sky peach-colored and the water a darkening purple. The freshly asphalted parking lot is empty, the new-looking museum dark. Neat picnic tables and mini-palms dot the deserted beach. The air is filled with a humid, metallic stink that we don’t immediately recognize as rotting fish. We walk to the edge of the water over crusty grey stones, stepping gingerly around desiccated corpses of tilapia.

Since the 1905 flood that created the Salton Sea, agricultural runoff has kept water levels high. While farmers staked their fortunes on the manufactured miracle of the greening valley, entrepreneurs saw promise in the new body of fresh water in the middle of a desert where temperatures regularly top 100 degrees. Mullet, corvina, sarvo, and tilapia were introduced into the Salton Sea starting in 1907, and over the next four decades, its beaches became a tourist destination. The massive engineering blunder was refashioned into another economic opportunity for the region, offering visitors fishing, boating, watersports, spas, and birdwatching under the hot Southern California sun.

In the second half of the 20th century, as the populations of San Diego and Los Angeles ballooned and long droughts drained the system, water from the Colorado River became an increasingly coveted—and contested—resource. In 2003, the federal government started buying water rights from the valley to slake the thirst of nearby urban centers, and the Sea receded rapidly. Salt concentrated in the stagnant water as evaporating moisture left minerals behind, while fertilizers and bacteria caused periodic algae blooms that consumed the water’s oxygen, suffocating most of the Sea’s aquatic life. When the conditions are right, the festering sea can be smelled as far away as San Diego, 125 miles to the west. Tilapia is now the only remaining species of fish left, and ecologists predict that it will soon disappear as well.

We stare at the listless waves while holding our breath at the stink. Salton City twinkles across the water, convincing us to forgo our camping plans and take a chance on a motel. As we drive north and then south again down the empty highway on the west side of the sea, K hums along with the melodic ballad on the stereo: Take me for a fool, yes, I was, because I was a fool. “I already know that this song is going to remind me of this moment,” he says, as the shine of passing streetlights catches the stubble on his face. I want to roll my eyes but then I feel a pang, some stupid desire to forget my skepticism of him, his chronic, whimsical romanticizing, and capital “R” Romance in general. Instead I watch the light disappear, the sea and mountains and sky dissolving into a nothingness of black, and tell myself that it’s okay to enjoy something even as it fades away.

It’s 8.30 pm and Ray and Carol’s Motel in Salton City is dark and shuttered. A powerful wind has picked up, salty but without the tangy smell of rotting flesh. I ring the bell at what looks like the main entrance and a shirtless child flings open the screen door. He hollers for his dad, who lumbers down the stairs while he pulls a t-shirt over his shiny tattooed torso. “I’m Gary,” he says, extending his hand to both of us. “Didn’t think anyone was coming tonight!” There are no other guests in the motel; it’s unclear when Gary last had guests. The cost of the room is $65 in cash up front. “You guys filmmakers? Photographers?” We look at each other with surprise at his clairvoyance—we are both those things. “We get lots of people like that. You know, they come to check out the destruction. You need something that looks like a bomb hit it? Nuclear war? We got that here. Across the lake, Bombay Beach, they got that. Lots of destruction.”

Gary shows us to our room. It has two double beds and a roof deck accessible through a half-size door in the wall four feet off the ground. It smells like it’s been shut up for months, inhabited only by the smell of harsh cleaning fluids, dusty blankets, rust, salt.

We pick up a pepperoni pizza from a diner on the highway, the only restaurant in town open after 8.30 pm. At the gas station next door they sell snacks of dried shrimp, fishing gear, swim suits, guns, and booze. We grab beer and whisky and beef jerky to complement our dinner. Like my ancestors wandering the Sinai, I’d ventured into the desert with only the necessities: 35 mm film, condoms—and because it is Passover, a box of matzoh, the bread of affliction. “You’re allowed to eat bread if you’re actually wandering in the desert during Passover,” my dad had joked. But it’s fine. I’m committed to my little renunciations. My rituals are personal, adaptable, seemingly arbitrary—even pepperoni pizza can be Pesadik, as long as I slide the cheese and meat off the doughy pie and plaster it onto flaky flatbread before stuffing it down.

Neither water nor fish should be there in the desert, but they are, and they have been, for more than a century.

After we’ve eaten, K and I climb through the tiny door to our roof deck, one story above the motel’s dirt courtyard/parking lot. A blast of wind, combined with the beers we’ve already drunk, makes us slightly unsteady on our feet, and we leap into our flimsy plastic chairs to keep them from blowing away. The salty air and beer is making my skin tingle, and I am able to stop thinking about how K said he doesn’t know how to be my boyfriend, and that he still doesn’t know what he wants. For a woozy hour in the rustling darkness, I can imagine we are alone on the ocean at midnight, sailing together towards some significant faraway horizon.

In the morning the sun is piercingly bright, further intensified by the spangled waves lapping at the white salt-encrusted stones on the beach outside the diner where we eat lunch. A flock of birds, startled by nothing in particular, takes flight before resettling on the same muddy stretch of sand. Every few minutes they repeat this ascension and lazy return, as if disavowing any real commitment to the land.

In an unusual twist, human interference in the natural landscape has had an unexpected benefit, and the Salton Sea has become essential to the region’s bird ecology: as other habitats were destroyed by development, this man-made wilderness became an important resting and feeding ground for species migrating along the Pacific Flyway. Almost 400 species of birds have been sighted there, from common gulls and cormorants to rare pelicans and endangered bald eagles. Since 1930, large swaths of shore have been designated part of a National Wildlife Refuge—one of the most diverse in the west—and birdwatching is one of the last leisure activities still flourishing at the Salton Sea. But when already-high saline levels become intolerable, the Sea’s fish and flora will perish. Inevitably the vulnerable bird populations will suffer mass die-offs from famine and disease.

Water allows us to believe that we can transform ourselves and our world, making fertile landscapes where before there was only heat and dust.

The Salton Sea’s ongoing role in the ecosystem—its very existence—challenges the very notion of what nature means. Neither water nor fish should be there in the desert, but they are, and they have been, for more than a century. The birds, like their human neighbors, made the best of it, and came to depend on its existence. But now, with the changing politics of agriculture and development, combined with the budget shortfalls stalling water reclamation efforts, the landscape reverts to its original state, i.e. a desiccated salt flat, as opposed to what has for 100 years passed as “nature.”

We take some intentional wrong turns on our way back to the highway, passing a few low-slung ranch houses and converted trailers surrounded by chain-link fences. The streets and front yards are empty and quiet; it’s impossible to tell whether anyone is home. A community pool is just a dry, cracked cement basin, shielded from the road by a few droopy palms. Joan Didion describes the backyard pool as “symbol not of affluence but of order, of control over the uncontrollable.” But the swimming pool has always seemed to me less a symbol of dominance than a portal to change. Underwater, eyes closed and nose plugged, I can imagine I’m anywhere else on earth or in time, from the primordial oceans to the domesticated lap pool.

Water allows us to believe that we can transform ourselves and our world, making fertile landscapes where before there was only heat and dust. The vacant swimming pool doesn’t signify a failure of control, but the end of possibility.

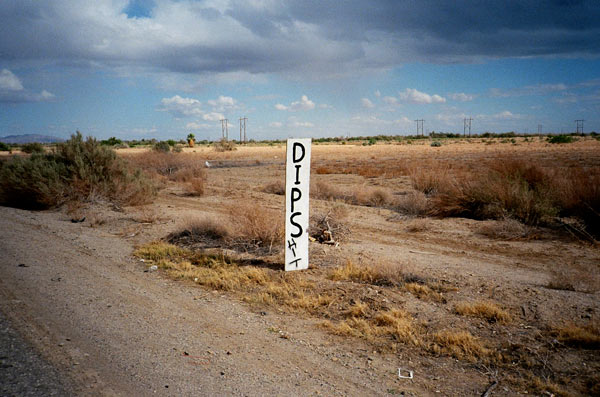

Like a naked girl wearing earrings, the deserted intersections of Salton City are decorated with glossy metal street signs that advertise adorably named streets: Shore Gem, Sand Quill, Sea Urchin Avenue. On my phone I map our location and am startled to see that although our surroundings look like a wasteland, we are actually meandering through a dense maze of carefully mapped but uninhabited cul-de-sacs.

In 1958 developer M. Penn Phillips poured millions of dollars into infrastructure for 25,000 lots, a planned business district, huge marina, schools, churches, and golf course. At first Salton City looked like a grand success; movie stars lent their sparkle to the new beach clubs and many of the lots sold quickly. But the area’s extreme heat and freak desert windstorms didn’t appeal to the masses, and the population leveled off at a few thousand. As the years passed, the Sea’s rising salinity caused mass die-offs of fish and birds, and receding waters left the beaches bleached and barren. After intense squalls battered the valley and flooded the sea’s shores in the 1970s, all that was left of Salton City was a small community of hardy residents unwilling or unable to leave a place that had never fulfilled its promise.

Driving south towards Mexico, we watch blurry tornadoes of sand spin themselves along the foothills of the Anza-Borrego Mountains. Gated green oases of agricultural prosperity break up the long stretches of Joshua trees and red desert. Is there anything more perfectly, frustratingly Californian than a lush fruit orchard surrounded by parched earth?

Brawley, California is just past the southern end of the sea, 20 miles from the Mexican border. The town, which is over 80% Latino, has been particularly hard-hit by the water shortages that have led to the Salton Sea’s environmental crisis. Surrounded by hundreds of miles of farmland irrigated by water from the Colorado, over half of the population of the town of 24,953 works in agriculture. At the turn of the 20th century, industrialized agriculture subsidized by state and federal grants made it possible for hundreds of thousands to make a life in the desert. A hundred years later, the gush of river water skips the valley for the sprawling urban centers of Southern California. When farmers take government buyouts on their water rights, their fields go fallow, and so do jobs in the community. To make matters worse, as the Salton Sea recedes, it leaves the ground parched and alkaline, leading to terrible, toxic dust storms that threaten what crops remain.

Brawley is adorned with signs for taco stands and check-cashing establishments. I announce my desire to check out the town thrift stores before I realize that Main Street is a long arcade of thrift stores, each filled with mountains of detritus: faded VHS tapes, crusty high heels, broken toys, stained sweatshirts from Kmart, a Criterion Collection Laserdisk of Five Easy Pieces. We smile apologetically at the friendly cashiers while halfheartedly wandering in and out of the stores, neither of us very eager to dig into the dingy piles.

We head north again, up the eastern shore of the sea, to the dusty desolate hamlet of Niland, (named after the fecund Egyptian River where Moses was set adrift). Construction crews have blocked off the road and when I tell K to slow down so I can ask the men in orange hard hats if we can pass, he refuses. “Can’t I just ask?” I say. “No, no, it’s fine, we’ll take the detour. They are working. I don’t want to bother them. And besides, I like detours.” Suddenly I’m disproportionately furious, enraged by the thought that everything—this road trip, our affair—is on his terms. I put up with his chronic confusion because I like him and our inside jokes, our sex, the long talks about art created and consumed, the way it feels to be in the passenger seat when he’s driving fast with the windows down. Because of all this I keep giving him my time. He wants to take the long way, and so we do.

We drive in silence as my anger recedes, climbing the hill beyond Niland to a plateau high above the Salton Sea. The flatland is punctuated by punky Joshua trees, low shrubs, and harlequin vehicles peeking out from behind spindly branches like badly-hidden Easter eggs. Since the closing of the Camp Dunlap Marine Barracks at the end of World War II, the government-owned land at the foot of the Chocolate Mountains has been inhabited by a transient population of artists, adventurers, and others who are compelled to go off the grid, beyond the reach of the law or the IRS. The hardscrabble existence of the desert valley is here taken to the extreme; the encampment, named Slab City after the barrack’s cement ruins, subsists on nothing besides the will of its residents to live the way they want to live. There are no public utilities, though there is a church in a trailer and a community stage, from which hangs a banner advertising a weekly Friday night party with bonfire and band.

I like to think that every time you visit a high vista you get to have an epiphany, but that’s obviously not true.

The trucks and trailers of Slab City are encrusted with gnarled pieces of found metal, plastic trash, and car parts; each domicile’s jeweled armor glints with the white heat of the desert sun. I wander over to a garden of brightly colored sculptures while K waits in the car. A yellow TV husk labeled WATCH in red rests on a splatter-painted red white and blue seat. I crouch down and look inside the box and am startled to see my own face reflected in the angled mirror, and the blue sky behind me.

A photographer explores an accidental sea in the desert, and a romance—both very much in flux—and returns with this meditation on transformation, control, and the truths we can learn from geology.

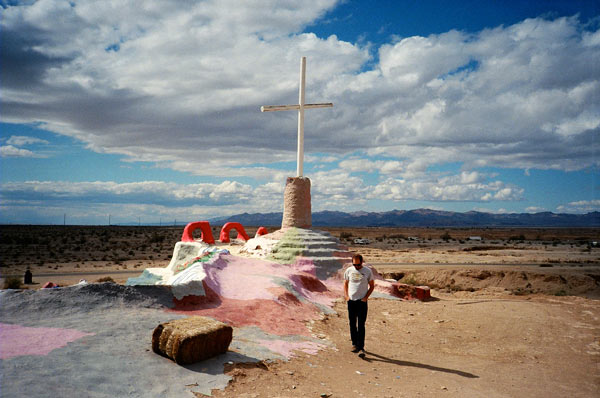

Between Slab City and Niland sits Salvation Mountain, the primary cultural attraction of the Salton Sea. Created by longtime Slab City resident Leonard Knight, the 50-foot monument constructed from adobe, hay, and paint is a riot of hues, patterns, shapes, and Biblical messages, topped off with a huge white cross visible for miles in every direction. After finding Jesus in the 1960s, Knight started hand-building stupa-like sculptures in the desert, eventually building the current Salvation Mountain out of found materials and donated paint. For over thirty years, thousands of pilgrims both secular and religious have found their way to Slab City to check out the monument emblazoned with the words “GOD IS LOVE.”

A photographer explores an accidental sea in the desert, and a romance—both very much in flux—and returns with this meditation on transformation, control, and the truths we can learn from geology.

We skirt the green-and-blue expanse meant to represent the Sea of Galilee and walk up the backside of the hill. At the top, I stand at the base of the twenty-foot cross and try to make sense of the colors undulating below. From my perch, I can see the wide sweep of the desert, and the glint of the Salton Sea in the distance. The wind is strong, whipping my hair and stealing the breath out of my mouth. K takes off his hat so it doesn’t blow away and comes over, puts his arm around me, and pulls me close. I rest my head against his shoulder, feeling the heat radiating from his body, and inhale the detergenty smell of his T-shirt. Wonder has replaced anger, and I just feel glad to be here with him. We stand together like that for a while, not speaking.

“The main business [of looking at a landscape] is a rediscovery and reevaluation of where we find ourselves,” writes photographer Robert Adams. I like to think that every time you visit a high vista you get to have an epiphany, but that’s obviously not true. Standing there, looking out, I’m not jolted by feelings of love, religious or romantic, but by something more modest—tenderness, affection, indulgence towards the endlessly, frustratingly ambivalent man next to me, for his thin, wispy hair that thrashes in the wind, for his perverted puns and disagreeable tantrums, and for the way he unintentionally lets out a high wheeze when I hug him tight. I feel affection for the stubbornness of Knight, the man who decided to paint the desert in rainbow colors, who put his life’s work into a monument so vulnerable to heat and sand and salt and wind and rain. Since Knight was hospitalized for advanced dementia at the end of 2011, the future of place is now in doubt. How long will the paint hold its pigment? How long until the words erode, the sands bury the Sea of Galilee, the storms wash away the hill on which we stand? How much do we fight to save something that isn’t built to endure? Nothing lasts forever in the desert, not even the most beautiful things.

A photographer explores an accidental sea in the desert, and a romance—both very much in flux—and returns with this meditation on transformation, control, and the truths we can learn from geology.

I see how optimistic it is to think you can get at the shiny reward through sheer stubbornness or desire or faith. Who you love is like where you are home—you don’t get to decide. You just do what feels right.

Twenty miles north of Niland, at the southernmost end of the San Andreas Fault, Bombay Beach is the lowest city in America. Three hundred people live here in a single square mile sitting 233 feet below sea level. The tiny, impoverished settlement was so plagued by the sea’s seasonal surges—augmented by the rainstorms that occasionally buffet the region—that engineers eventually erected a tall berm to protect homes. The wall cut through the existing hamlet, abandoning a swath of buildings to the ruinous force of the sea.

Gary of Ray & Carol’s was right: this is the place to see destruction. Burnt beams and broken foundations, bleached tree trunks, old and new bits of plastic, metal, wood—all of it sinks into the tidal muck. There is a faint hint of dead tilapia in the breeze and when I look down, I realize that the white beach is made up of shattered fish skeletons, billions of tiny vertebrae crunching underfoot. Just as K is about to take an illicit public pee, a vacationing family of five, plus slobbering golden retriever, stumbles out of a minivan. Their sunny wholesomeness makes our visit feel morbid: people live here, even if they are hidden by the locked doors and shuttered windows, and we’re grave-digging their backyard. K and I had wanted to explore a weird part of America, to find distraction from our problems in the exotic peculiarities of a foreign landscape. But instead we’ve encountered something much more familiar—a badly mangled thing too necessary to give up.

K hits the gas pedal, and as we accelerate, we both shout “yeah, Yeah, YEAH!” while the cars drop behind us as if deferring to our speed.

Geologists say that the Salton lowlands held inland seas many times before, when the sands were soaked by chance floods caused by weather or earthquake. But with no consistent water source, the ancient lakes always evaporated, leaving behind salty sand flats and traces of extinct mollusks embedded in red rock. For centuries prospectors spoke of finding ruined ships in the desert, ghost vessels washed inland by calamitous storms in the Gulf of California, 150 miles away. Even today, there are whispers about missing treasure, Spanish booty and hauls of exotic pearls sunk in the silt at the bottom of the Salton Sea. Bombay Beach’s gutted buildings and stripped electricity poles evoke the masts of those long-buried ships, as if they were still lingering on the course of some unfinished voyage—suggesting thwarted promises, dashed hopes, great treasures lost to history. As I watch K wander toward the rusted earth-moving machine parked at the shoreline like a tired swimmer, I realize that I used to believe we were working together to dig up a cache of real happiness. Now I see how optimistic it is to think you can get at the shiny reward through sheer stubbornness or desire or faith. Who you love is like where you are home—you don’t get to decide. You just do what feels right.

The highway that follows the western shore of the Salton Sea runs parallel to the train tracks of the Union Pacific line, and as we drive north, a long stretch of rolling metal containers keeps our pace. K tries to say something but I shush him, transfixed by the strangeness of moving through space in tandem with the colorful metal boxes. K hits the gas pedal, and as we accelerate, we both shout “yeah, Yeah, YEAH!” while the cars drop behind us as if deferring to our speed. We hurtle through space while I think of geologic time—how it is both linear and cyclical. I picture the growing of mountains, the eroding of rock, the widening of oceans, the evaporation of lakes, the evolution and extinction of species, over and over again, nothing spared from the epic violence of slow change. I think of all the people I’ve ever loved, the relationships that failed, the joys punctuated by sadnesses, the sadnesses modified by new joys. From geologic time we know that although things may seem to end, they have ended and began again as something new many times before. This gives me hope somehow.

Our circuition of the Salton Sea is completed at the Recreation Area, where we spend some last minutes staring out at the water. The beach still reeks of dead fish and the museum is dark; it’s unclear if it is ever open. California’s budget woes closed down the park this summer, and Governor Jerry Brown eliminated the official Salton Sea Restoration Council in June. But at this moment in April, months before bureaucratic inaction will effectively sign the Sea’s death warrant, there is more life than we’ve seen for hours: men with spindly fishing poles standing patiently at the edge of the water while pelicans frolic in the waves. A tern hovers at eye level, buffered in place by the wind. The sun drops toward the Santa Rosa Mountains and before we drive away for good we stand near the car, shielding our eyes to check out an isolated segment of rainbow suspended in the pale blue sky.

We leave the valley before the light disappears, taking the steep Pines to Palms Scenic Byway over the San Jacinto Range. K grips the steering wheel, his knuckles white as he cuts back and forth on the hairpin turns. I open the window to soothe my motion sickness. Below shine the lights of Palm Springs, Indio, and Coachella, each one a twinkle of life in the hostile desert. I watch as it all disappears behind us. The air temperature plummets as we rise high above the desert. All around the mountain is decorated with sharp rocks and awesome boulders, rubble thrust upward by powerful seismic forces, the vertiginous scale of geologic time. As the landscape vanishes into an opaque alpine fog, my eyes prickle with tears. “Are you okay?” K asks. I am.

Rose Lichter-Marck is a writer, editor, and photographer living in Brooklyn. You can see more of her photographs on her blog. She is on Twitter at @roseolm.