By Alexandria Peary

I’m beginning to think it’s all about “declined” versus “rejected.” At a recent national writers’ conference, the representatives from the online submissions manager service Submittable were passing out tchotchke sweatbands printed with “DECLINED” in the site’s signature font. I imagined some writer heading to the gym to work off his frustration with a literary rejection from that day’s post or inbox, a man who pushed his round glasses up his nose, lived his early twenties through the 1970s, was mostly bald and beyond middle age, and had to wear a white sweatband, contrasting with the fashionable gym garb of those who look like twenty-first century kore hopped up on muscle. I imagined him going at it, on that Stairmaster, dripping sweat everywhere, sweat that would eventually blur the letters of DECLINED.

I don’t really want to be writing about literary rejection; doing so reeks of a khaki-colored fart of ambition mixed with complaint. I am interested in the different qualities of rejection—ones beyond the thin mimeographed no-thank-you strip, the gauging of chances based on the relative heft of a stamped self-addressed envelope pulled from the mailbox. It seems that anonymity is one form of rejection. Take the early nineteenth-century American poet Felicia Hemans—often called Mrs. Hemans on her book covers—who penned the play The Vespers of Palermo and the poem “Casabianca,” widely popular in her day (“The boy stood on the burning deck / Whence all but he had fled, / The flame that lit the battle’s wreck / Shone round him o’er the dead.”). Who reads Mrs. Hemans’ “The Wild Huntsman” these days? Hemans became a household name and was given to schoolchildren to memorize, a dubious honor. Even if you win such-and-such prize and this-and-that award, you can easily be rejected over the long haul.

Then again, in the nineteenth century, you might have to endure a type of societal rejection simply because of your gender or for other reasons now categorized “socio-economic.” In the 1944 book put out by Allyn & Bacon as part of its Academy Classics series, American Poetry, there are many a Henry, John, Joseph, Edwin, Oliver, and Charles, in addition to Bayard, Sidney, Clinton, Witter, Archibald, Hamlin, Joaquin, Eugene and one Abram, followed by the ambiguous Danske, Epes, Francis, Joyce, and Vachel. The first unambiguous female is Mary Ashley Townsend, author of “The Creed,” with its eerie optical opening, “I believe if I should die, / And you should kiss my eyelids, when I lie / Cold dead and dumb to all the world contains, / The folded orbs would open at thy breath.” Anne Bradstreet is categorized as “Unpoetic Poetry” characteristic of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. No mention of Phillis Wheatley or her Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. That these women were omitted is a testament to the extent that society tried to ensure their anonymity—tried to keep them among the declined for later centuries.

If a woman was remembered for her writing, it was because her writing embodied her womanly morals.

“Declined” seems polite, part of an interchange sculpted by etiquette, one where tea has been offered and the other party, after careful deliberation, pauses, and then says, “I think I’ll pass on tea right now. It doesn’t suit my current purposes.” “Rejected” seems to tell a story about junior high girls in leg warmers with similarly feathered haircuts issuing a taunt and then departing as a herd while laughing in the same key. School bus purring like a belligerent yellow sphinx. Then there’s “dejection”: a hybrid of the two.

Women writers in the nineteenth century—when creative writing really got going as a possible profession—faced more rejections than declines, though probably more than a spoonful of dejection. Hawthorne’s phrase for them, a “damned mob of scribbling women,” is a rejection, and so is his view of their writing—“trash.” Lasting literary success was defined by the author’s personal qualities: if a woman was remembered for her writing, it was because her writing embodied her womanly morals. These rules and regulations were evident in the pages of Godey’s Lady’s Book, the preeminent women’s magazine of its time. The pages of Godey’s were regularly used as a sort of chat forum for women writers at all career stages to describe their writing successes, explain their techniques, vent their frustrations, and dispense advice. Much of the advice either reiterated the rule of womanly morals or talked about the side effects of success in light of that rule. In an 1859 edition, the editor of Godey’s, Sarah Josepha Hale, warns that a woman’s writing will “usually sink into oblivion…where the moral power does not uplift woman’s genius.” Women were told that it was more important to walk the talk and maintain pure households than to describe such households in their stories and poems. One article from February 1867, titled “Woman’s Fame,” advised: “We would, therefore, impress on all our intelligent and gifted country women, more particularly on the young, that there is a field, and a wide one, too, open for their genius, beside that which afforded by the present facility of feminine authorship.” Namely, housework.

The gist: if you have friends and lead a normal, healthy life, you would never consider sending your work out for publication; if you’re gripping a fountain pen right this moment, you’re a freak of gender.

In fact, if you were a woman writing in the mid- to late nineteenth century, you could get rejected by your peers for being accepted. In an article from 1864, “My First Venture,” a woman writer recounts the reactions of her family to the news of her first publication. From another room, the writer overhears her aunt’s withering response to her publication:

So much for going out with family to celebrate one’s first publication. Women were routinely told (even by men in high places—say, editors of magazines and newspapers) that there was something wrong with them for wanting a writing career. Timothy Titcomb (real name J.G. Holland and the founding editor of the influential Scribner’s Monthly Magazine, who once solicited Emily Dickinson for publication) wrote a self-help book called Letters to the Joneses in 1863. In one letter, addressed to a “Miss Felicia Semans Jones,” which—though I have no proof—sounds suspiciously close to Mrs. Felicia Hemans, he writes to women who want to be writers:

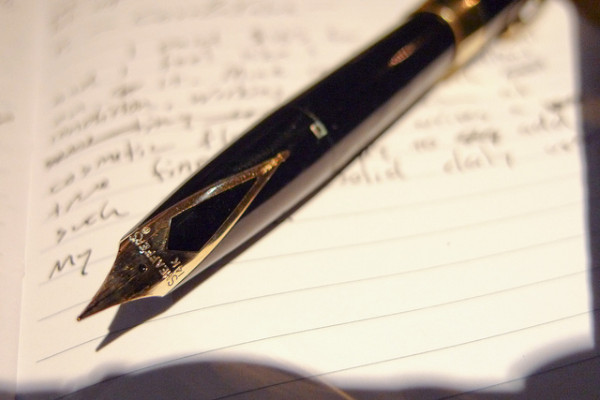

The gist: if you have friends and lead a normal, healthy life, you would never consider sending your work out for publication; if you’re gripping a fountain pen right this moment, you’re a freak of gender. Happiness did not seem destined for women with overt literary ambition.

In The Myrtle Wreath of 1854, in a chapter tellingly titled, “Is She Happy,” Anna Cummings Johnson describes an “acquaintance”—a successful woman writer who is so depressed she is literally weeping in a corner because she feels domestically unfulfilled. As Johnson tells the reader, do not covet the fame of a successful woman writer, because that writer is suffering: “When women reigns in any other empire than home, it is from stern necessity, which converts her into a martyr.”

A true jewel of rejection is Thomas Carmichael’s 1870 Autobiography of a Rejected M.S., a little volume one can still purchase as an off-print. As you might guess from the title, it’s a personification of a literary text: the main character, a manuscript of a novel, recounts its experience of editorial rejection. Its author, Lucille, fell into poverty upon the death of her father, a decline in fortune that leads her disloyal fiancé to terminate the courtship and move on to a wealthier woman. Lucille hopes to earn money to support herself and her mother through the manuscript, which she writes in one night and immediately sends out for publication the next day. The Manuscript describes how its author proceeds the next day to the editorial offices of a generic Weekly Gazette, carrying it under her shawl, close enough so that this novel Manuscript can hear Lucille’s anxiously beating heart. The Manuscript adores its author and is probably more in love than her disloyal suitor.

After a stint in the waiting room with two other author-wannabe, Lucille gains entrance to the famous editor’s office, where her reception is less than favorable. The editor assumes Lucille has penned a sentimental novel (which she has: the Manuscript is about a loss of love remarkably similar to Lucille’s experience) and informs Lucille that he usually rejects work by women without actually reading it. He tries to discourage Lucille from further literary endeavor by citing Samuel Johnson:

After Lucille departs for home, the editor deposits the Manuscript into his desk drawer—a dark prison—where our Manuscript talks itself out of a panic attack by telling itself that greatness often requires tribulation. The Manuscript daydreams of a grand outcome: “From a simple story in a gazette, I assumed the shape of a neat little volume, prettily bound, and in universal demand at all the railway stations, making Lucille’s fortune and my fame.” When the editor retrieves the Manuscript from its literary limbo in the drawer, he gives it a cursory reading and throws the Manuscript into a trash bin.

It’s not a sheet of paper rolled up, its words gently rubbing one another, but instead is a voice, a swirl of pixels and bytes shot through a virtual carnival ride.

Lucille returns to the editor’s office, and the Manuscript overhears their interaction. Lucille is apologetic and expresses her worry that she’s wasted his time. No worry, he replies, because he didn’t actually read her whole submission. Lucille explains that she is “no longer compelled to write.” It appears that with a single rejection, Lucille’s literary ambitions vanish in a poof, but she does manage an exit retort: “Although I hate sentimentality, I am afraid I could not avoid sentiment.” To wit, the Manuscript adds that its contents are important because people who have lost love have a “heart widowed of love.”

I imagine my own manuscript, stuck in a pile multi-modally with my other titles. It’s not a sheet of paper rolled up, its words gently rubbing one another, but instead is a voice, a swirl of pixels and bytes shot through a virtual carnival ride of routers and servers and fiber optics and IP addresses and through networks it doesn’t see which make it all like a night flight over a major city. To your left, folks, would be the Eiffel Tower if conditions were better.

We could probably do a scholarly investigation and track down the exact moment in which Mrs. Felicia Hemans’ status started to disintegrate. Her nadir might well be the moment she became an ironic prop in Saki’s short story from 1919, “Toys of Peace,” in which a mother persuades her brother to give more pacific presents on Easter to her two sons. No more avuncular gifts of toy soldiers—instead, figures of notable civilians such as a local sanitary inspector, John Stuart Mill, and Mrs. Hemans, described as a “poetess.” The unimpressed nephews swiftly adapt the peaceable toys for their own means, transforming them into soldiers in a battle in which Mrs. Hemans stabs an enemy in the heart and red ink is splashed.

One moment you’re a grade school girl putting a unicorn sticker on the cover of a notebook containing your very first poem. The next you’re leaning over a MFA application, and then you’re middle-aged on a Sunday morning, glancing over at the small family of journal and book bindings of your published works on a nearby shelf.

The measuring of time used by literary production and effort. As a mother, I grip a sort of dipping stick, like one used to check a car’s oil level, but it’s of time used, and what I pull up is a rainbow instead of oil. The measurement, like notches on a wall in a closet or laundry room indicating a child’s growth, indicate the amounts of your children’s childhoods passing while you are sealed away in your room to write.

Yet it comes to this moment, of applying the pen tip to the ice sheet of the paper, the pads of the fingers pressing themselves like keys into each chiseled alphabet, the pastel sparks arising from contact with the paper which is contact with the self. It’s the joy, the sheer joy, of writing in the moment, of being alive in this moment and writing, no matter the long-term fate, the dust of the alphabet, the rising motes with writing on their edges, the books moving toward dust.

Alexandria Peary’s third book of poetry, Control Bird Alt Delete, received the 2013 Iowa Poetry Prize. Her nonfiction is available or forthcoming from New England Review, Hippocampus Magazine, and Superstition Review. She teaches writing at Salem State University and runs a blog on mindful writing: http://alexandriapeary.blogspot.com/.