Come to me, he said, my melancholy baby, but I wondered if this was for the second time, and well rehearsed. Why are you being so nice to me? I said. Dream on, he replied.

That was day four; on day one, I found underwear, not my own, in my underwear drawer. Are you talking to me? he said, when I asked. Speak up, he said, and I was yelling my head off and draped the underwear, a silky thing of threads and holes, over my head. See this? I said. I’ll never understand you the way you want, he said; and besides, I can’t sit still that long, and don’t ask me.

I was put in my place, and my place was way in the back behind the plant, making shadow puppets on the wall. But, I also clean the kitchen, and run to the store for ice cream, and whatever he needs that minute.

That day, I ran, thinking all the way that the golden bowl was broken, and now what?

Henry was fifty, and I fifty-one, and we were both eye candy, luscious with all the bad parts driven into our character, so all you saw was smooth and ideal, touchable, although we didn’t want fingers or loose lips too close to the merchandise. That’s how we met. I was swimming in the pool in a lane all my own, pushing out my ink in bubbles and wrinkles on the water’s skin. I was a swimmer who could race one minute and drown the next, and Henry had me under the gills on the dorsal side and pulled me ashore, hawking, spitting, crying, and panting. Ahoy, he said. Do you live around here?

I can’t see without my glasses, and the lifeguard was holding them, with my bathrobe and flippers. I couldn’t even see where he was sitting. Jerry? I yelled, and no answer, so I clambered out of the pool, sitting on the concrete lip, with Henry hauling up next to me. Are you looking for these? he said, dangling before my eyes my cat glasses and polka-dot coat, a towel and flippers. Slapping on the glasses—although my nose was running and mouth hanging open to gasp—I saw the Ken doll that Henry was, even sitting with his back rounded like a turtle.

I said, he said, do you live around here? What are you deaf?

I kept looking through my glasses, while brain—my weakest part—interpreted.

I’ve lived many places, and lives to match, I said.

With that, he jumped into the pool and swam a lap. I’m going to ask you one more time…

I know, I said, do I live around here? Who wants to know? I said.

And, with that, Henry was in the locker room, putting off and putting on. When he was dressed, I was still sitting there, starting to dry off and evaluating in that slow way I had.

One more chance, he said, pulling me by the hair to look into my upside-down face.

Across the street, I said, and it was true.

So, he followed me there and invited himself in, issuing a strong critique. There was something wrong with everything. He didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. You got nothing, he said. Yes, I said, go on. And the nothing you have stinks. Thanks, I said; what are you a decorator?

He touched things and rubbed the dust off his fingers, sniffed, and gazed round with hard eye. I like it here, he said, and no better compliment had ever been paid me, because so out of the blue. You do? Somewhat, he said, and partly because you’re here. And, with that, I was grabbed and pushed to the wall for a round of kisses that nearly crushed my skull. The pain I could take, because, in my case, pain is sensation, and I’m pretty much unplugged—the brain-body connection weak and flickering, the body-world almost nil. I’m in a state of happy hibernation, except for the curiosity that pulls me out of the cave and into trouble.

After the head smack, I was pushed into the bedroom, way down at the end of the corridor. Down, down, down. Keep moving, he said, and we ended up in congress. My hair was still wet.

What do you have to eat? he said. Never mind, he said, I can just imagine.

What? I said.

Well, he said, science plunges ahead. So, up he jumped and down the corridor to yank open doors and drawers, returning with a box of OJ. Want some? he said. I watched the yellow stream from his mouth, down his chin, and onto his hairy chest. What are you laughing at? he said.

Next morning, a loud knock on my door. How come, he said, your bell doesn’t work? I’ve been standing here for ten minutes.

I don’t want to hear that bell, I said.

And why?

It hurts my ears.

Reconnect it, he said. Or else.

Or else, what?

But, he was already down, down the corridor, dragging me behind. Do you like me? he said. Before I could get a word out, he said: Well, I want you to do this and that, and that and that, before Friday, if you want me to come back and love you.

I considered. After a lifetime (or thirty years, let’s say) of nonstop but variegated love, was this necessary? I tend to be philosophic, so unfolded a few arguments, which got me nowhere. My axiom is never say no, even if the no is the number that comes up. I shaped the word in my mouth, but could never spit it out.

What are you looking at? he said. Wake up!

I grew up in a town with streets called Health, Wealth, and Wisdom. Health and Wealth were streets; Wisdom, an avenue. I had a friend on each one, and we were all poor, sickly, and slow, but the addresses were our first slap of irony, and it smartened us up, you bet.

We were a dime a dozen, and at that, no bargain, so no one could short sell us. And I, the least among them, but men had always liked me, old and young, fat and thin, smart and dumb, mick or wop—which is all we had. I held them off for a while, thinking myself or dreaming myself into a wimple with hands folded under long, flowing black. Left alone, for a change, to mumble and creep about in perfect harmony with rocks and chimes and fancy rituals. I loved the bread and wine, and how it became something better and never went back, even when eaten. I liked the resting state, and this was it, in the days of old. The rest of my life was candy and housework. My daddy would bang on my door: Are you readin’ in there? Stop readin’! I loved a book, especially one I didn’t understand, so that I lapped the edges of things everyone else knew, or people used to know, and soon was an authority. But no one wanted to listen to me. The nuns drew a circle on the board and put sex in the middle, but wouldn’t spell it out; nor would they write it with a dash in the middle. They put an X, X marks the spot. Don’t go in, they said, and don’t even think about it.

The fathers said more, because they loved to air the subject and dangle it in front of our girlie faces, some grim, some gape-mouth, some shut-eye, some (like me) gazing out the window at the future. How could you not think about it when they made it sound so luscious? We were stunned into silence, then herded into chapel to blurt our confessions to the priest, eating his cake and having it, too.

And it was all inside that chalk fence, which you could still see, after they’d rubbed it out, because a new chalk on a satiny black board, after we’d licked it clean. It’s still there now with whatever they thought they were fencing inside, and I know in my heart, they knew it all and were hoarding it to have it to themselves in the gloom of their minds, and in meditation, with hours to kill, eyeing that naked male strung up on its lumber, and just hanging there, year after year, for all to see, sad, hurt, and evergreen.

Throw all that crap away, said Henry, and come follow me. First, we drove out one dark winter night, my car tailing his car through wood and winding road, to the gingerbread house, I was sure, to be roasted in the oven, gobbled, white meat and dark, gizzard and heart. And if that were my destiny, so be it, as my mother always said. Many are called, but few are chosen. Don’t try to get out of it, and I never did.

At the end of the line was a cottage of one big room with windows like eyes, all open, looking onto woods and field. I heard the rabbits scream in the night, chased, trapped, and chewed by the fox. The owls hooted, doves crooned, birds squabbled, and crows launched their air raids. I was what was inside the fence, alone there with Henry.

Henry was my landlord. I paid the bills and cleaned the sink; I raked the leaves and put out the garbage. It was a loneliness I savored: as far as the eye could see, nothing but weeds, vines, streams, and hidden beasts.

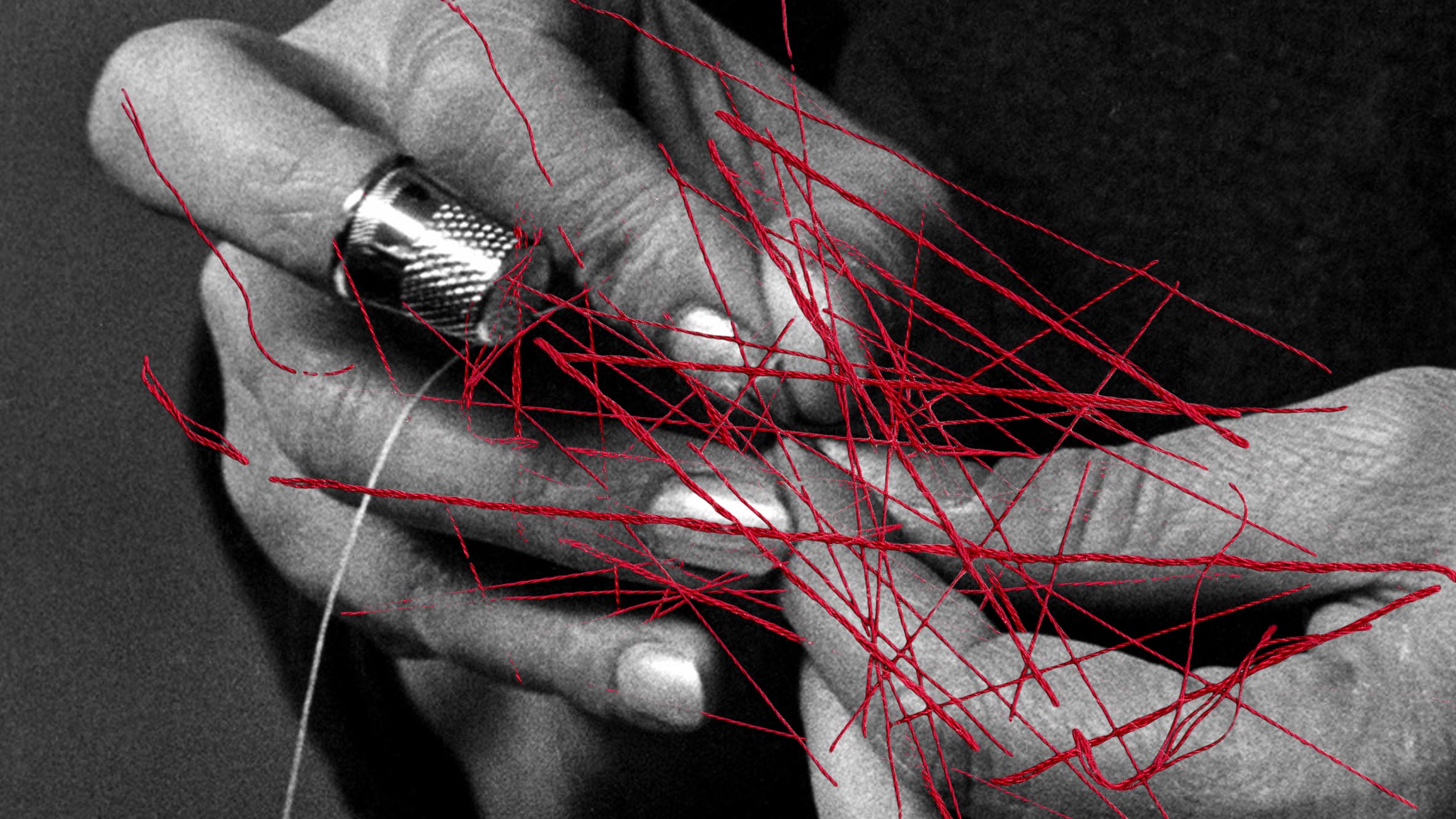

But, nothing lasts, if you start with nothing. Living there with nothing of mine, and everything of Henry’s, ringed round by the emptiness of nature minding its own business, I decided to start a business. Fine sewing, knitting, and tailoring, things that ran in the family. We were elemental, and made no bones about it, born fingering things and gulping the air. I made an apron at four, and a clothespin bag of the same fabric. Jumpers, skirts, bureau scarves, doilies, gimp chains, and potholders. Give me something and I’d turn it into something else. Maybe not as good, maybe better; often, hard to say.

I put a little plaque at the end of the driveway on top of the mailbox. Matchbook Weave and Stitch: you name it, I’ll make it. First thing free. Sliding scale.

My first patron was the hag across the road, Delilah X.L. Llewelyn-Whitechapel, widow and heiress, she of the hunting dogs and hunting steeds, although no longer a hound master, there at all the parties with a glass in each mitt. She strolled over with a pack—Queeny, Mac, Goony, and Frog, the house dogs—while the kennel dogs yipped and yapped as they spotted the gate closing and the frolicking pets.

I was ready with a charm bracelet of cheap trinkets: sewing machine, shears, thimble, spool, seam ripper, button, and five sharp needles. I was playing with Henry’s dog, Nero, spinning the charms in front of his eyes as he snapped at them, screaming when a needle bit into his soft palate. He’d already eaten the thimble. We had that kind of relationship, edgy and punishing, and it went both ways.

Nero greeted the dogs with barks, growls, and nips. It was four against one, sending Henry’s dog whimpering under the porch. The quartet remained there, peering in the windows and cursing what was inside and out, hurling themselves against the door, fighting, biting, and snarling. It was hard to hear yourself think, but when Lady Whitechapel pointed to my bracelet, I gave it to her, and she snapped it on.

What do you have for me? I said.

Just an idea, she answered. Where’s Henry?

Gone, I said.

Gone where?

Just gone, I said. Were you looking for him?

None of your smart answers, she said; now, pay attention.

The order was for a baker’s dozen of linen napkins, initialed in baby blue and buttercup with Delilah’s first, three middle, and two last names, including the hyphenated one. She handed me a scrap of paper with the engraving. Just like this, she said.

The curlicue mess was unreadable, even to a sharp eye like mine. It was a snarl, and now the pets were snarling.

Time to go, I said.

Don’t rush me, she answered. I’ve got another order for you, miss. How long have you been here?

Without waiting for an answer (two weeks), she said, I knew the first one, the one he married.

Right, I said.

She had lovely taste. Better than his, she said, looking around. I know him well, she added, and there’s not much to know. She winked at me. But, be assured, she went on, that whatever there is, I know it.

After a pause, and before turning to launch the dogs: And then some, she added.

Well, I said, we all know what we know.

She spun around. You ain’t seen nothing yet, to quote a man, she said, snapping a finger at the dogs, jumping for joy.

Nero? I said, when they were out of sight. Come out, come out, wherever you are.

Nero was crying, and sure enough, a big bloody gouge taken out of his left flank. I patched him up with a stinging swab and pillowcase wrapped round his middle with one of Henry’s belts. I gave him a treat of watermelon and baby marshmallows, his favorite, and calmed him down with aspirin and a dose of cough medicine. He was asleep when Henry came home from his job selling rugs, steaming shrimp, and piloting the water taxi. It was a three-parter with no intermission, seven days out of seven for a full quota of daylight.

You! he said, pointing at me and then at the slumbering hound.

Mrs. Llewelyn-Whitecastle did it, I said, cross my heart and hope to die. Remember, I babbled on, how I was going to hire out as a seamstress? Well—

Silence, he said, holding up a hand. Nero Nerone Caesar Augustus! he said, and the dog came to attention, tail wagging like a metronome, and crawled over meekly to lie at his master’s feet—pilot boots, smelling of the sea. What happened, Nero? Tell me, he said to the drooping dog, an actor. He barked an answer, pathetic in its puniness.

What you don’t understand, I said, was the indoor pets were here.

And you did what! he said, so loud Nero started barking, leapt to his feet to stand by the door and guard us with his life.

Unbuckling the belt and unwrapping the cloth, there was the bite, a wound, blood mixed with Nero’s blond fur, and a patch of nastiness. What do we do next? I said.

Call the doctor, he said, and our day was spent on the wound, the doctor, the call to the hag, the hard words for all, and the temptation to flee, cooled by the time of night and the fact that my car was blocked by Henry’s car, truck, tractor, and the stuff piled in a hill to go to the dump.

I started sewing. The hag had given me the cloth and the threads, knowing that whatever pittance I earned by this and other piddling tasks (the horsewoman said she’d pass the word to the neighbors) wouldn’t even cover the gas we used to haul the dog to the vet. That’s how I started falling behind and heaping up debt and backlog, plus simmering resentment. Now look what you’ve done!—if I heard it once, I’ve heard it every day of my life.

I started a little sewing school: tears and laughter as the neighbors plied their needles, pricking their fingers and stabbing their knees. We sat in a circle and passed the peace pipe (meaning we all took up smoking and tippling, the usual thing for ones left at home all day to file our nails and vacuum the rugs). One gal supplied the corn liquor from her brother’s still (they were all landed and off the grid), and her sister, the smokes from a granddad’s milk store on the county line. We tried not to get too fat, sitting on our asses and telling jokes. The hag was too snooty to join in but inspected the wares, starting with the hankies and moving to pillowcases for the trousseau for Penelope Ann, marrying the farmer’s son, set to inherit the leases on everyone’s land. He supplied all the horse feed, and then some. Penelope Ann, the end of a long line of Pequots, was in tenth grade and pregnant. The farmer’s family had been there just as long (hired hand, sharecrop, steward, dog master, migrant, tramp). The country club, just as ancient, would host the affair. Everyone had an opinion, most bad, including the bride’s connections, but she was a plain Jane, and the father’s farm is adjacent to their Pequot holding, the join just a matter of cutting a few fence poles.

I loved a wedding, and was sewing as fast as I could, fixing everyone’s snarls and bêtises, doing the fancy work and finish. My gums were bleeding from breaking thread with my teeth; and I had full set, beautiful they were, a little buck, a gap, and a headful of fillings, meaning gold, silver, and the new white stuff. I could calm a whole room of nuts and cranks with my smile and the flash of white, with glints of precious metal.

These, for me, were new connections, different from the nuns and priests and the chums on Health, Wealth, and Wisdom; and yet, not that different, because still local with long, tangled roots and the dreams and nightmares to go with them, half remembered, half enacted. But their accents were different, with a Southern twang and the quirks and palaver of rustic class. They all had pet names: Roots, Frolic, Tommyboy, Bags, Red, Hatchet, Moxie, for the men; and the gals: Mars, Cappy, Happy, Snappy, Fudge, Borax, Daffy, and Rover. I couldn’t bring myself to shout them out, so said: Mister and Missus, or Miss.

They were bad sewers, but I kept them on, because I craved the company and needed their help. I hadn’t told them how I had to bust out, and soon. Henry had built me a tiny slave shack on top of a hill, but within shouting distance of his place. Stay put up there, and don’t let me hear a peep. I liked having my own place, even if unheated and the size of an outhouse. The floor dipped and sagged, and the whole thing tilted at a sick-making angle, but it was home.

Henry would appear, day or night, fling open the window, and stick his head in. All the animals congregated on the raggedy rug: Nero, Sarah, the mother cat, and her son, Eddie. Henry was jealous of the hold I had over these parasites. I didn’t feed them or speak their language, but they tracked me everywhere and loved the slave quarter, just their size. How’s business? Henry liked to say, never waiting for an answer. Business was slow, because my team had no gift for the work although they loved it. By my labor alone, we pulled together all the sets of things a young bride stores, until the marriage stales or sours, then rejoices to find, whole and perfect, wrapped in tissue paper. The things trump the deal, more so when the kids come along. But, months had gone by, winter to spring, and only one trousseau for one trunk, and a meager payout divided among four. We used it to advertise, and to lay in a machine. This was life, make no mistake, and it was good.

But, no more orders came in, when the hope-chest goods were fingered and assessed. They were old-fashioned things, and even brides were trucking in Chinese material by way of household gods and impedimenta. The hell with this, said the sewing circle, and off to the stables they went. Grand National, Steeplechase, cubbing, hunt cup, eventing, dogs and e pluribus unum. I waved from the window as I saw them radiate to their farms.

I sat lonely at my machine and ran up a slew of even lines at different tensions with scraps of material left behind. With these ruffles, runners, and tucks, I decorated my quarter; and, abracadabra, that was my next career, decor, and they all signed on. We fixed everything with fluff and furbelow, drape and duster. We slapped on paint and took a Cutex to the dentils, egg and dart, cornice, arch and pillar, chair-rail and bumper. Creams, Wedgwood blue, black, and red. The thrill of it, as these dowdy barns took on a spark and shimmer, to their own era true. I had the taste; they had the dough, but when the work was done, what? It was, once more, hunting season, and the song of the hunting horn and the frenzied dogs called them away. Then, it was bachelor cotillion, New Year’s revels, and trips to the islands and fat farms.

Stand and deliver, Henry said, sticking his head in the window.

What was left after my careers was loving, the X inside the fence, now mon plaisir. I devoted myself to its discipline. Waking early to refresh my skin in the springs of the earth, oiling my hair and eyebrows, inking my fingernails, and wrapping myself in the last of the gorgeous remnants. I paraded across the lawn (tracked by the parasites, who craved a game) in my veils and soft shoes. I mounted the ladder to peer into Henry’s den, perched above his workshop. Resting my arms on the windowsill, I made delightful faces and licked the glass, tapping with my blood-colored nails. Hey, there, you with the stars in your eyes. Henry laughed to see me in my act, and pulled down the shade. Go way, I heard. Don’t haunt me.

I bathed in Tide and Sweetheart soap, crowning at the bathroom door, highlighted by candles and sticks of incense. I mastered the forty-five arabesques of nook and cranny, bull’s eye, and feathered arrow. It was satisfactory, my report card said. “S” or “P,” but nothing better, or more particular. Juices, honey, fluffs, glitter, power, ointments, scent, order, and chaos.

So, I took a breather and cultivated my own garden. I was far along in life, but not trashed yet, or rotting, although the skin of my arms was chicken flesh, and my eyesight tunneling, my hair like dandelion fluff, but I never acted my age, so compare me to a summer’s day, you could.

The parasites weren’t much company, and Henry was in his own fugue state, seeing, as he was compelled to see, the wreckage, the melt and errata, of his own run on earth. He had his jobs, his castle, a dog, and a few fruit trees, but instead of adding up, stampeding to a rousing climax, his singularity was looking to him like the run of the mill, as I might put it. The glory was not in the past nor on the spot where we stood, eye to eye, not next week or in a decade’s bright span. It was sputtering out, and what did it amount to?

I could capture his dovelike hand in mine. Who cares? I’d say. Who’s counting, and look the other way! For that, he’d show me his teeth, and the dog would growl, sky darken, turkey vultures land in a pack on the roof, the power go out, and things come to a stop.

Take up hunting, I said, buy a nag, a mare, a steed, a pony, a warhorse. I saw the thought circulate in the roulette wheel of wish and will. Nero and Henry started taking long walks, tramping up and down the curving road that was our street, all farms and faraway places. They’d return, and Nero would sleep for hours while Henry tinkered in his shop. What are you making? I asked, looking at his bare back curved around his work under a forty-watt bulb and all the bikes and license plates and dream machines that people pile up then store till the end of time, burning their eyes and hurting their feelings with what’s broken, half-assed, set aside, the sullen junkyard that ate time.

I get it, I said to the back. Say no more. Go in peace.

He pivoted, charged, grabbed in his two meaty fists my windpipe; and shake, shake, shake, until a new day dawned in my head.

Why are you hurting me? I said.

Don’t know, he replied; do you?

Beats me, I said. But thinking on, I saw it all in a different light. Truce? I said.

Yeah, why not, he said. Shake. Removing his mitts from my throat and pumping my hand with both of his. You’re a good egg, he said. Now, leave me in peace. Scram. I’ve got business.

He would tread the future, silver-haired and alone, is what I saw, king and solitary of his castle. And why? So no one would see the decline and fall, not even Nero, who’d go first. I moved my truck to the quarter and waited. I ate at a diner—no fridge, no stove, no taters or sop. The parasites slept on the mangy rug, all but Nero, whom Henry dragged down by the collar, whimpering and sneezing.

It was a time of quiet, peaceful agony. What do you think will happen next? he said one morning, throwing open the window to see the parasites arranged in a circle, Nero already whining, so divided the poor dog was, and choked with guilt, no matter whose side he was on.

You’re asking me? I said, my heart a stone sinking to my feet.

I’m telling you, if you get my drift.

Meaning, I said, out, out, damn spot?

Meaning is up to you. You’re the great parser, sister Sue. Where are your sewing pals?

Gone, I said.

Figures, he answered.

Such is life, I said.

Not for me, he replied. And with that, the window slammed shut.

The omen came next. For a week of nights, Nero slept on my floor, and when I woke, I found his eyes waiting for mine to open, and a questioning, doubting look: Why am I here? I read.

Well, go down, if you need to, I said.

He barked, and I opened my flimsy door, and out he flung.

A change of season, but no plan or guide, by star, riddle, or hint.

I sat upon my couch, cross-legged, to think, and what a futility it was since I had never tracked the wilds in Henry’s thick skull. He gave me no clue, key, or legend, trusting that his will be done on earth, by some reckoning that excluded a second. The wastes inside my skull were his, as I spelled out in pods of speech the this and the that. He knew I was peaceful, a conjugant and congregant, lazy and serene, a music box with no crank, spieling away.

Days passed, months. The ladies returned to sit in the quarter and renew the acquaintance, but also to see if I had a job for them, as hunting season had passed, and the days grew long and sultry.

When did they start to see me as a carcass, something left behind by the tractor, reaping in a narrowing gyre, for the vultures and hawks? That was one thing, but I also caught a glimpse of roadkill in Nero’s sharp eyes.

The end was coming, if not in sight. Henry started vanishing for hours, days, nights at a time. How come? I was afraid to ask, and disappearances alternated with an even grimmer silence. His back was always turned, a snarl on that Ken-doll face, closed up like a fist.

I worked around the edges, tidying things and whistling while I worked. I started ironing his sheets and socks and played out servility, light and dark, comic and tragic. There wasn’t anything I didn’t try—the sincerity of a baby, the hypocrisy of a courtier, the light touch of a shadow, the speed of a gazelle, monkey faces, and dudgeon. My joints started to harden with the effort, and my whole character changed from pot roast and Harvard beets to puddling jello. If I’d been a fifty, I was now a debt, a sucking hole of clown-like misery. Flesh fell off me, my gums bled, and my eyes were black as a coon’s. All was weakness and debility, as worse came to worst.

And then I started gambling. I’d been landlocked, a chattel or serf, for a decade; I’d aged a century, was good for nothing, and my sire was sending me packing. He hadn’t said so, but his eyes (when I could see them) were stone; or just hollows, empty cups of bone. When he looked at me, his brain stopped wheeling, a stopped clock.

One day, when I took my car to pick up staples and sweet meats, I came home to a chain across the driveway. Keep Out, it said, Beware of the Dog, Posted, it said. One Way, and Beware All Ye Who Enter Here. A stop sign, skull and crossbones. Secure Personnel Only. Proceed at Your Own Risk. Private. Keep Out. The chain was wired and wound with barbs, a carpet of glass on the ground, a trench beyond.

Aha, I said. At long last, the verdict.

I left my car, a junker, on the field, out of harm’s way, and tracked in with bags of goods. Henry met me with arms folded. Attack! he said to Nero, and poor Nero was stumped.

Attack? I said. Did I hear right?

Everything you touch, you wreck. What did you buy me?

So, in we went, and here’s the rub: something was different. I hadn’t darkened his door in a month of Sundays, and it struck me that someone was sleeping in my bed. How did I know?

I put on my thinking cap; I shut my eyes tight, using my finger to point due north. Wheeling around, in full powers, I smelled a rat, opened my eyes to see Henry’s grinning skull, all teeth and slits for eyes.

It was then I thought to look in the crevices where things are hidden and found the underwear, the lingerie, the skivvy, linen, underdrawers, pantaloons, bloomer, mini, brief, knicker, culotte, foundation, corset, garter belt, hiphugger, dainty, Fruit of the Loom, X marks the spot; and spotted, too, wrinkled and balled up with a something sticky and hard.

Before Henry could snatch them, I had them on my head. Behold, I said. Into thy hands, I commend my spirit.

He left the room—hard, because there was just the one, jumbo-sized, with everything in it.

Come to me, he sang, his back turned, and hands blocking his ears, my melancholy baby, but was he singing to me this once?

I walked over, the black doily still on my head, pulled down over my forehead like a helmet.

You’ll need that, he said, where you’re going.

Going where? I said.

Home at last, he said. You live around here?

Nope, I said.

Well, skedaddle, go home, your mother’s calling you.

Is this it? I said, salt tears tracing a zigzag and dripping off the edge.

Bye, bye, blackbird.

I’d come full circle and was ready for the shot to the moon.

But, I opened wide my dripping eyes and saw: nothing, zip, a box of air. Where, why, who, how, how come, whence, why for, what, how long? I sang, and repeated, mutating the order.

A hand clapped over my mouth. None of your palaber, he said.

Palaver, I said. Not “palaber.” But, a little of that is called for, yes, given how you delivered me like a cargo onto this wasteland, and left me stranded.

Not stranded, jilted.

Not jilted, skunked.

That’s the card you picked, girlie. Ladies’ choice.

I pondered. Was it?

Does she live around here? I said.

I found her where I found you.

In the pool?

In the neighborhood where you used to live, lonely as a cloud, and can’t swim worth a damn.

I could learn.

I remember your flippers.

Am I already a memory?

A good dream.

That touched my heart, and I left by the door, blowing a kiss to the pets lined up in the driveway. Take care of your father and God bless, I said.

A car was coming up the drive, nearly ran me down, busted through the chain and signage, the glass and trench.