Rome–New York

Tomas Tranströmer–Teju Cole

The title of Teju Cole’s exhibition of paired photographs comes from the poem “The Scattered Congregation” by Tomas Tranströmer. Here are the relevant lines: “Nicodemus the sleepwalker is on his way / to the Address. Who’s got the Address? / Don’t know. But that’s where we’re going.” The exhibition will open at Ithaca College’s Handwerker Gallery in April.

Teju Cole has written that Tranströmer is a “master of solitude” and that his poems hover “on the edge of the unsayable.” In the Rome–New York pair of photographs, we see the walkers—on their way to the Address! Cole the photographer is watchful but he holds back. Even in the act of speaking to us, he is alert to stillness. (To recall another fragment of Tranströmer’s: “I come upon the tracks of deer’s hooves in the snow. / Language but no words.”) I admire the fact that all the images in this exhibition—pierced by shadows and brightness, speech and silence—are imbued with their own lasting mystery. Like magical poems that leave brief traces of light on the fingers of a reader who is now alone in the middle of the night.

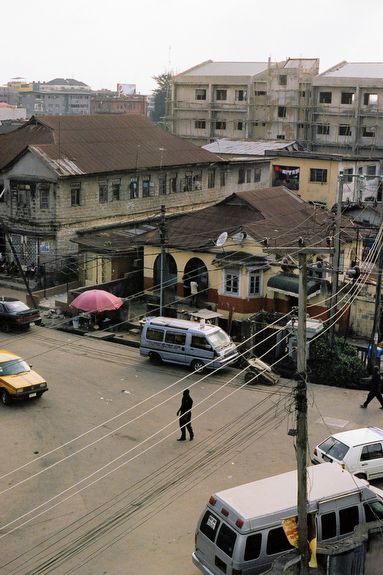

Lagos–New York

Roland Barthes–Teju Cole

The Frenchman, glancing through a magazine, pauses at a photograph from Nicaragua. What has made him pause? The picture shows soldiers and, behind them, two nuns. He has been drawn by what he calls the photograph’s duality, the presence of those two discontinuous elements, nuns and soldiers, that do not belong to the same world.

In Teju Cole’s paired photographs, it is difficult to find a focus on a familiar kind of political contrast. Or the familiar rhetoric: Look, this is the First World! And this is the Third World! Instead, the photographer captures a gesture, and later, on the editing table, notices the echo elsewhere. The first image sheds light on the second. One place calls out to the other. A figure in black in New York City strides toward another figure also in black in Lagos.

I’m reminded of V. S. Naipaul’s admiring remark to Raghubir Singh: “This is pure pictorialness. It doesn’t make a comment…” Or Naipaul’s sly remark after Singh has said that protest is “much too easy” to show with the camera: “People have misused it. One has gone to endless exhibitions about the wickedness of the South Africans.”

Sasabe–Margao

Susan Sontag–Teju Cole

Susan Sontag tells the story of a photo exhibition in Sarajevo. Paul Lowe, an English photojournalist, had been living in Sarajevo for a year, and he mounted an exhibit at a partly wrecked art gallery. He showed the pictures he had been taking in the city and also the pictures he had taken some years earlier in Somalia. The Sarajevans were offended by the inclusion of the Somalia pictures. They didn’t want their suffering compared to others, not only because they didn’t want their pain to be measured on a misery index, but also because they were opposed to a gesture that reduced their history to a mere instance. Sontag wrote: “It is intolerable to have one’s sufferings twinned with anybody else’s.”

Teju Cole has twins. Sasabe, Mexico: A makeshift memorial to women who died trying to walk across the Sonora desert to Tucson. In the background, crawling to the horizon, is the U.S.-border fence. Margao, India: This was the scene one night after the photographer had visited his wife’s aunt and her two children. The aunt is young, in her early fifties, and she had lost her husband recently.

New York–Rome

John Berger–Teju Cole

In late October 1967, two weeks after Che Guevara was killed in a village in Bolivia, John Berger wrote an article commenting on a photograph that had been taken in a stable. It showed Guevara’s unwashed corpse laid out on a stretcher placed on a cement trough. A sharply dressed Bolivian military colonel was pointing at a wound on Guevara’s bare chest, while behind and around him others watched. For Berger, the photograph resembled a famous painting by Rembrandt, “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp,” where the cadaver at the center was also the subject of an examination and a formal lesson. I have used Berger’s article often in my classes. Like the men in the middle of the picture, I imagine Berger, and even myself, pointing into the frame.

Berger’s choice of the two images was acute. He also mentioned another image, Mantegna’s painting of the dead Christ. The purpose of such comparisons—or, perhaps more accurately, of such juxtapositions—is preeminently pedagogical. In Teju Cole’s pictures, however, there is little to entertain pedantry. The comparisons he makes offer a more delicate pleasure. The legs of pedestrians at a zebra crossing in New York City, their shadows splitting like trees, is mirrored by what the photographer sees in Rome. The branches lean toward one another and make a pattern.

Jersey City–Cabo Frio

Elizabeth Bishop–Teju Cole

In most cases, I didn’t ask Teju Cole about the circumstances in which any picture was taken. But in this case, for some reason I did. He told me he’d taken the first picture when he had gone to see Radiohead perform in Jersey City. It was a daylong music festival, with lots of bands playing, and something of a carnival atmosphere. The other picture is from Rio Janeiro state, when Cole was driving to the beach at Cabo Frio. It had rained earlier and he had stopped for gas. I was happy that I had asked Cole about this photograph because he revealed that it twinned perfectly with the poem “Questions of Travel” by Elizabeth Bishop, who had, of course, spent a long time in Brazil. In her poem, Bishop has a skeptical take on the alleged pleasures of modern travel: “Think of the long trip home. / Should we have stayed at home and thought of here?” She likens this hunger for wonders of the world as mere childishness. Then there is a turn. The poet pictures what would have been missed if the traveler had not left home: “But surely it would have been a pity / not to have seen the trees along this road” and “Not to have had to stop for gas and heard / the sad, two-noted, wooden tune / of disparate wooden clogs / carelessly clacking over / a grease-stained filling-station floor.”

Delhi–Pittsburgh

Teju Cole–Teju Cole

Early in Teju Cole’s Open City, his narrator Julius has wandered into the American Folk Art Museum. The museum is hosting an exhibition of paintings by a nineteenth-century artist named John Brewster. It is quiet inside. Julius’s description of Brewster’s paintings of children with their serious faces builds an aura of profound stillness. Then he tells us that Brewster was deaf. And most of the children he had portrayed shared his disability; they were pupils at the Connecticut Asylum for the Education and Instruction of Deaf and Dumb Persons.

What is the silent transaction that takes place between the artist Teju Cole and his subject? We look at the framed faces—in the autorickshaw in Delhi, illuminated by invisible taillights, and two others, one adult, one child, in a room in Pittsburgh—and their downcast eyes. (Only the child, more innocent, is looking at the camera.) What is it that absorbs their attention, which seems turned elsewhere? We are ushered into a mystery we cannot part, and, more certainly, into the intensity and alertness of the camera’s look.

New York–Rome

Gilles Peress–Teju Cole

When Gilles Peress was taking the famous photographs that were collected in “Telex Iran,” he was conscious of being a Westerner and an outsider at, say, a religious rally in Tehran. The horizon appears in a nervous tilt, faces are sliced at different angles, and more often than not there are obstacles and screens that occlude or divide the frame. Instead of conventional captions, Peress has supplied only the record of telexes exchanged between him and the Magnum agency offices in New York and Paris. The viewer has to work hard to bring coherence to the scene, and often that is impossible.

Was Peress an influence on Teju Cole? I doubt it, and I say this only because I haven’t encountered the former’s name in anything Cole has written; nevertheless, what I think Cole shares with the Peress of “Telex Iran” is a commitment to complicate the act of seeing. I look at Cole’s juxtaposed photographs from New York and Rome—the woman in the hijab is out of focus, because the focus is on the vampire’s giant tongue reaching out behind her; the other side approaches another figure, the darkened nun in her habit—and I am reminded of Peress, and, more particularly, of how Islam has been seen and also not seen.

Barcelona–New York

Alice Oswald–Teju Cole; Jack Kerouac–Teju Cole

“. . . Her name was Abarbarea / A young man found her in the hills / He took one look at her shivering freshness / And stripped off his clothes / In the middle of his astonished sheep / He jumped off a rock right into her arms . . .” —from “Memorial”, Alice Oswald

“That little ole lonely elevator girl looking up sighing in an elevator full of blurred demons, what’s her name & address?” —from Jack Kerouac’s introduction to The Americans by Robert Frank

I read Alice Oswald’s marvelous book of poems after Teju Cole chose it as the best book of 2011 on Salon.com. And in the months after Open City came out, I remember mentioning to Cole more than once that he ought to work on his version of The Americans. He could do America off-kilter in grainy black-and-white images, sure, but more than that, he would be best poised to tell the story of how, in the time since Robert Frank immortalized them, the Americans had changed.

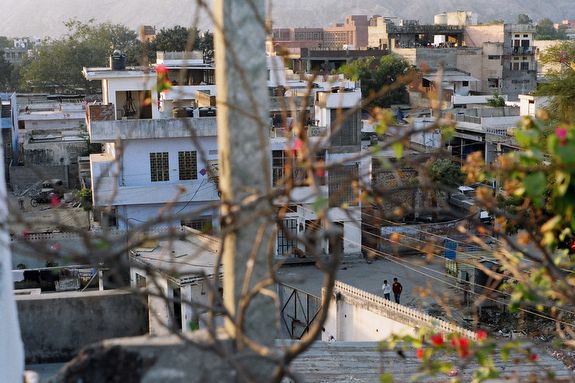

Jaipur–Baltimore

Jacques Derrida–Teju Cole

In a video available on YouTube, you can hear Jacques Derrida explain why he didn’t allow his photographs to be taken or used in the public domain until 1979. He liked photography but not author photos, whose staging he found ridiculous and comic. He also wanted to be in control. Then Derrida appeared in a public debate and photographs of him started appearing—although, ironically (and yet appropriately), the first photograph to appear with his name under it showed only a friend of Derrida’s from the back “with a head that was completely bald.”

Teju Cole shares with Derrida more than the latter’s distrust of author shots. Cole, in what I think of as a Derridean fashion, wants to complicate an event or an articulation. “One of the gestures of deconstruction,” Derrida says, “is not to naturalize what isn’t natural, to not assume that what is conditioned by history, or institutions, or society is natural.” We are looking at scenes of the city—or cities, united in a binary relation, working together and also against each other; we are struck by what is the visual counterpart to a preliminary or a prior question; instead of a plain or transparent view of the city, we are confronted by a skein of knotted branches or metal stairways and beams.

Derrida lays out the principle in Memoires: For Paul De Man: “Deconstruction is not an operation that supervenes afterwards, from the outside, one fine day. It is always already at work in the work.”

Jaipur–Kathmandu

Raghubir Singh–Teju Cole

Jaipur is desert; Kathmandu is mountain. In Teju Cole’s photos, we are not aware of the difference in altitude, because both cities share a horizon of badly laid-out electrical wiring. Both places have shuttered walls and share the air that is brightly striped with shadow lines. In both places men rely on two-wheeled animals for transport, though, in a pinch, the flat carrier over the back wheel, with horn-shaped supports, can accommodate a passenger. Nevertheless, women—and cows—mostly choose to walk.

Jaipur was the birthplace of the great Indian photographer Raghubir Singh. “I’m unembarrassable about influence,” Teju Cole has written in another context. Raghubir Singh is an influence. Particularly the Raghubir Singh who told an interviewer: “Making the edges clean makes the pictures too precious. This was understood by Degas and the Japanese scroll painters before the photographers.”

São Paulo–Palouse

Michael Ondaatje–Teju Cole

In Ondaatje’s The English Patient, the young woman Hana recalls a line from Stendhal: “A novel is a mirror walking down a road.” The novelist is a photographer. Here is Teju Cole in the “My Hero” column in the pages of the Guardian: “Michael Ondaatje’s work taught me how to be at home in fragments, and how to think about a big story in carefully curated vignettes. All his books were odd, all of them ‘unfinished’ the way Chopin’s Études are unfinished: no wasted gestures, no unnecessary notes.” In the pair of São Paulo–Palouse photographs, the images work as fragments, a common element of visual poetry uniting them, producing what Cole calls “a journalism of fleeting sensations.” This is the singing photojournalism—to quote Cole’s twinned phrase—“of the barely visible, of the barely important.”

Lagos–Tivoli

Toni Morrison–Teju Cole

“The ability of writers to imagine what is not the self, to familiarize the strange and mystify the familiar, is the test of their power.” This was Toni Morrison, in her powerfully argued 1992 essay “Black Matters.” A skilled artist, especially one with a political bone in their body, will displace our assumptions. This is done to call into question our private prejudices, or sometimes to bring to the fore our fears. Look at the pair of images from Lagos and Tivoli. Quiet images, slightly mysterious, drawing the eye deeper into themselves. For some reason, when first looking at them, I thought of Julius in Open City: on a walk one afternoon, he sees men caught in a brawl and then, looking farther up the street, he sights “the body of a lynched man dangling from a tree. The figure was slender, dressed from head to toe in black, reflecting no light. It soon resolved itself, however, into a less ominous thing: dark canvas sheeting on a construction scaffold, twirling in the wind.” The next moment, I remembered Julius at an earlier point in the novel, as he sits seething in a cab with an African driver. They have had a tense conversation. “I was in no mood for people who tried to lay claims on me.”

New York–New York

Dhoomil–Teju Cole

There is a poem by the Hindi poet Dhoomil that I like very much (it was the last poem he wrote before his death) in which he instructs the reader that to find out how words become poems, you must look for—and read—the human who has fallen among the letters of the alphabet.

Is this the sound of iron that you have heard, Dhoomil asks, or is it only the color of blood that has fallen and mixed in the earth?

And then at the closing of the extremely short, and powerful, poem: “Don’t ask the blacksmith / about the taste of iron. / Ask instead the horse / which holds the iron in its mouth.”

New York–Brooklyn

Don DeLillo–Teju Cole

“She’d heard of him, a performance artist known as Falling Man. He’d appeared several times in the last week, unannounced, in various parts of the city, suspended from one or another structure, always upside down, wearing a suit, a tie and dress shoes. He brought it back, of course, those stark moments in the burning towers when people fell or were forced to jump.” That’s from Don DeLillo’s novel, Falling Man.

Teju Cole was in New York City on the day of the September attacks. But these sunny pictures are not from that day. I cannot be utterly certain, but I doubt that these people are looking up at anything dire. I say this because Teju Cole is a performance artist, too; he teases our assumptions and plays with our fanciful fears.

Nogales–New York

Arundhati Roy–Teju Cole

The God of Small Things, a story of two twins, has as its epigraph a line from John Berger: “Never again will a single story be told as though it’s the only one.” (Roy’s book came out in 1997. It had a twin: Michael Ondaatje’s In the Skin of a Lion was also published the same year. Like twins that share a secret mark, both books had the same epigraph from Berger.)

A formidable writer, as well as political activist, Roy will appreciate the act of witness undertaken here in the picture from Nogales. We see Maxine Hong Kingston looking reflectively at the U.S.–Mexico wall. She was grieved by the sight of it. She later declared, “It is an obscenity.”

Teju Cole has cast as that picture’s twin the image of our friend Wah-Ming Chang, writer and performer, preparing for a dance in New York. I’m drawn to this pairing for an additional reason. The dancer’s gesture, caught in the camera’s mirror, took me back to The God of Small Things: the stoned Kathakali dancers, performing scenes from the Mahabharata, whirling in an imaginary battlefield strewn with corpses.

A closing remark. The faces of both women are visible in outline but we see them more fully as mirrored reflections. For the photographer, the importance of the mirror! On the last page of W. G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn, we read the following:

“Sir Thomas Browne, who was the son of a silk merchant and may well have had an eye for these things, remarks in a passage of the Pseudodoxia Epidemica that I can no longer find that in the Holland of his time it was customary, in a home where there had been a death, to drape black mourning ribbons over all the mirrors and all canvasses depicting landscapes or people or the fruits of the field, so that the soul, as it left the body, would not be distracted on its final journey, either by a reflection of itself or by a last glimpse of the land now being lost for ever.”

Teju Cole is the Distinguished Writer in Residence at Bard College. His novel Open City won the PEN/Hemingway Prize and was shortlisted for the National Book Critics Circle Award. His photographs have been published in the New York Review of Books, A Public Space, and other journals, and his solo exhibition “Who’s Got the Address?” has been presented at the Old Secretariat in Goa and is forthcoming in April at Ithaca College, NY.

Amitava Kumar is the Professor of English on the Helen D. Lockwood Chair at Vassar College, and the author of numerous award-winning works of fiction and non-fiction, including Husband Of A Fanatic (a New York Times Editors’ Choice), Bombay- London- New York, and Passport Photos. His most recent book, A Foreigner Carrying in the Crook of His Arm a Tiny Bomb, received the 2011 Page Turner Award for non-fiction from the Asian American Writers’ Workshop.