While talking with Cole Sayer, I often felt a need to bring the discussion back to what we deem “Painting Problems.” These are an odd set of issues which are really placeholders for people, and so consequently consist of proper names with the word “problem” dangling from the other end of a hyphen; think the Michael Krebber-Problem, the Daniel Buren-Problem, the Wade Guyt – you get the point.

One could say that before the dominance of Aesthetics, this type of noun-heavy discourse wouldn’t have made any sense. It wasn’t until Modernity ensued and painting became a Problem–meaning the very relationship between the practitioners and the field was problematized–that discourse, and its requisite authors, and their respective production of meaning and content was born.

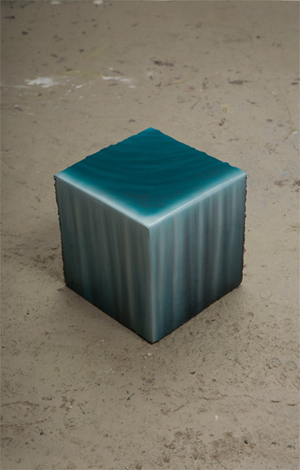

Sayer’s work literally flattens this staid relationship between author, form, and content. In Sayer’s paintings content is squeezed between his own subjectivity and the computer–the apparatus and functionary–and pressed through a curatorial cheese cloth. Traditional oil paintings make reference to Jumbotron screens and expressionistic marks are generated using a Wacom Tablet. What appears to be a dense marble sculpture reveals itself to be an airbrushed plastic shell. It is a process whose end product might be best understood as surface-concentrate.

These works have no substrate, no undercurrent, no content to be unearthed. There is only a plane to glide along. In this way reading Sayer’s work recalls Foucault’s cartographic ballet across Velazquez’s Las Meninas. However, our dance across a work by Sayer doesn’t reveal what Foucault called, in The Order of Things, “representation as it were, of Classical representation” but rather, a bumpy orange basketball. The quasi-perverse surfaces of Contemporary Sport (Jumbotron screens, receiver gloves, balls) become the flattening and binding agent of surface and depth, of sign and referent, of parodic allegory and artistic sincerity. Like the floating Jumbotrons they depict Sayer’s luminescent surfaces always seem to stare back at us from another dimension, one Giorgio Agamben called “evanescent ghosts [in] the hyperborean no-man’s-land of aesthetics.” This is why Sayer’s objects so often seem like Infra-thin holograms, flickering on the outskirts of presence.

—Sebastian Black for Guernica

Sebastian Black: Having never been to your studio before and just doing internet research, I thought there would be more of a net emphasis to your work. I didn’t realize it was going to be translated into super stuff.

Cole Sayer: I don’t think it’s a jump to say that most young artists are net artists. Social media is a kind of curatorial phenomenon and most work is viewed in the liminal space of the internet. But aside from that, I am interested in a kind of bridge between the digital and the physical. All of the paintings and sculptures in my studio are completely reliant on the computer. They’re made in the same way as it would be in software, building structures and then rendering them with textures…

Sebastian Black: Like you can just click “water” and then it’s rippling.

Cole Sayer: Right, and then the next second it’s diamond-plated. I’ve also been looking at professional sports a lot as some sort of readymade link between digital and analog. Everything surrounding, say, an NFL game looks more and more like it’s out of a gaming environment. The marketing behind it mimics a kind of CGI-future-techno fantasy. The jumbotron at stadiums functions as a ready digital intermediary between the spectator and field. The list goes on.

Sebastian Black: Is there something about actual sports, like this weird, slightly aggressive, male subjective-driven thing going on?

Cole Sayer: I played football in high school. I was a terrible athlete but I worked really, really hard at it. The whole time it was based in these clichés about conquering your opponent, and trying your best, and never giving up, which I was really seduced by as a teenager. These all rely on a clearly defined relationship between the self and other, hero and villian, right and wrong. I’m interested in uncovering the same hidden binaries in stock art practices.

Sebastian Black: Well it’s the same kind of general mythology as being a Painter. It’s always a kind of struggle against something–you know, Pollock in the studio driving himself insane or something. Which is the same as a Nike ad where some guy’s running up the steps of the stadium all night.

Cole Sayer: That’s perfect! You and I had this great conversation the other day where we admitted what bad painters we actually are. Bad at making, I don’t know, pictorial magic happen out of form and color. But still we’re invested in the medium to varying degrees. I think for me, that lack of innate talent regulates a level of sincerity. It’s no wonder I treat the studio as if I’m putting in extra hours at the gym. Of course, if anyone were to read too far into what I just said, there are a lot of problems with it.

Sebastian Black: It’s interesting because, even though they’re very much paintings, it seems that–aside from sports–their whole reason for being is locked in the stuff they’re made out of.

Cole Sayer: I’ve been using a lot of the newest in art supply technology, the newest acrylic mediums, catalyzed resins, etc. I’ve been thinking of them like a pair of receiver gloves. It goes back to the sports reference: it’s just this thing that’s supposed to give you a little extra competitive edge.

Sebastian Black: That’s nice. It’s like the typical discourse in modernism of what painting is about. It’s just that now that there’s so much weird plasticy shit, you know? At first when I picked up one of your sculptures, I was really surprised by the weight. I expected it to be this heavy, solid porcelain object or something.

Cole Sayer: They’re very deceiving in that way. In Nashville all of the architecture was themed. So in the nice suburban areas you’d find a country cottage, a Tudor-style home, and a French chateau on the same street. My parents’ house growing up was a “Contemporary Modern” design, very angular and sparse. At some point they hired interior decorators to fill it with artwork, modern furniture, and shit. They came up with all of this weird stuff that’s supposed to look like modern art, found mainly in these furniture boutiques in the suburbs. So they all had this high production sheen, all anonymous and perfect.

Sebastian Black: But yours aren’t direct representations of that. If you saw it in the house, you’d think, “That one’s weird.” There’s something slightly off about them. It keeps them from actually being that thing–they approach something but they don’t quite do it. Everything’s a bit of a prop.

Cole Sayer: It’s a peculiar thing to make a prop piece that’s supposed to reference another kind of art. As soon as they become props there’s immediately this huge remove to it. You can reference the aesthetics of something without engaging in its politics, but they are also strangely activated by that. It has to be considered to be a prop, because it has to be just enough to get the job done in the act of viewing the work. It’s deceptive but, if uncovered, it immediately asks the viewer for the benefit of the doubt.